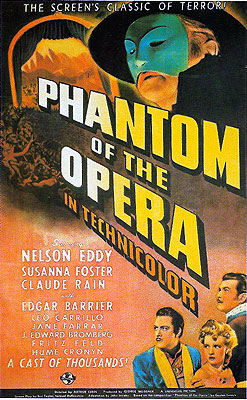

The Phantom of the Opera (1943) *½

The Phantom of the Opera (1943) *½

On the first season of “The Muppet Show,” there was a running gag in which Sam the Eagle, eager as ever to elevate the quality, tone, and general respectability of the program, was forever pushing Wayne and Wanda, “the world’s most morally unobjectionable singing duo,” whose shtick was even more desperately uncool than that of the Vaudeville dinosaurs and American Songbook bores that Jim Henson and company spent most of their efforts affectionately skewering. As was so often the case with Muppet characters of that era, Wayne and Wanda had a specific real-world antecedent. They were based on Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, a pair of MGM contract players who starred in eight massively popular musicals together between 1935 and 1942. You know the kind of movies I mean— drippy, sappy love stories with bloated run-times, hordes of extras, settings designed to show off the chops of the costuming department, and operetta vocal stylings built around the counterpoint of tenor or baritone vibrato against a keening soprano that you can feel in the roots of your molars, but only your dog can fully hear. Audiences of the 30’s and early 40’s ate that shit up, and although none of the other studios could do it quite like MGM, it only stands to reason that they’d all try from time to time.

Eddy’s contract with MGM lapsed after I Married an Angel, the final film pairing him with Jeanette MacDonald, after which he became something of an anomaly in studio-era Hollywood— a successful free agent. His radio shows, concert performances, and records sales combined to make him the world’s top-earning singer, so he didn’t really need the movies as such. Just the same, he wasn’t going to turn down a good gig, and strictly from a business standpoint, Eddy’s first freelance film project must have looked like a fine gig indeed. Universal, you see, were finally getting around to a talkie remake of one of their most beloved silent hits, The Phantom of the Opera. Most of Universal’s horror pictures had been cheap and rather junky affairs ever since cost overruns and production delays on James Whale’s Show Boat lost the Laemmle family control of the studio in 1936. The new owners took Universal a step back toward its Poverty Row roots by filling up the production schedule with B-grade genre programmers whose principal virtue was being a notch or two up on the quality scale from the output of firms like Republic, Monogram, and PRC. Nevertheless, because status did matter, the reorganized Universal would still splash out occasionally on something much grander, just to remind everyone that they remained a major studio— but because profitability mattered more, those bigger pictures were subjected to a degree of budget discipline at least equal to that imposed on the hour-long monster romps, the mass-produced Sherlock Holmes sequels, and the Lon Chaney Jr. Moustache Mysteries. As befit its heritage, the new Phantom of the Opera was going to be one of those new-model Super Jewels. And that, at the very foundation of the project, is where it began to go catastrophically astray.

For the viewer, however, the catastrophic going-astray starts in the opening scene, a seemingly interminable excerpt from Friedrich von Flotow’s 1852 comic opera, Martha, or The Market at Richmond. After all, when you hire Nelson Eddy, you’re fucking well going to have him sing! Eddy plays Anatole Garron, lead baritone of the Paris Opera, and over the course of this performance, it becomes apparent that he’s besotted with Christine DuBois (Susanna Foster, one of Universal’s own contract warblers, who would return to this much darker territory just once, in The Climax), a chorine of sufficient talent to have recently been promoted to understudy for Biancarolli (Jane Farrar, also in The Climax), the opera’s star soprano. Christine, however, is dating Raoul Daubert (Edgar Barrier, from War of the Worlds and The Giant Claw), an inspector of the Sûreté, the French counterpart to— and indeed the inspiration for— Britain’s Scotland Yard. If that strikes you as an odd choice of suitors for a professional singer, that’s also how it strikes Villeneuve the orchestra conductor (Frank Puglia, of The Boogie Man Will Get You and 20 Million Miles to Earth). Villeneuve counsels Christine that the life of an artist can be understood only by other artists, and that by encouraging a policeman’s courtship, she is setting herself up for the premature termination of her singing career. I’m sure this was all gripping for fans of Eddy & MacDonald musicals, but for people who came to see The Phantom of the Opera…

There’s a third man, too, sniffing after Christine, but violinist Erique Claudin (Claude Rains, from The Invisible Man and The Wolf Man) isn’t like the other two. He’s much older, for one thing, pushing 50 while Raoul and Anatole are both in the prime of life. And more importantly, while Garron and Daubert vie openly for Christine’s love and attention, Claudin has taken such a low-key approach that the girl has barely even noticed him pining for her from the depths of the orchestra pit each night since she came to work at the opera. So far as she’s concerned, Erique is just the kindly but awkwardly shy old weirdo who just about works up the nerve to say hello to her every once in a while. But that shy old weirdo has somehow been financing Christine’s singing lessons under one of the finest teachers in Paris for some years without the girl ever catching on where the money was coming from. Note to Claudin: although it certainly makes sense for a middle-aged man in pursuit of a chick less than half his age to sweeten the deal by throwing money around, the sugar daddy thing doesn’t work unless the girl knows who her sugar daddy is!

Claudin has bigger problems than his extravagant generosity going unnoticed, too. He’s coming down with arthritis or carpal tunnel syndrome or something in his left hand, and his playing has suffered enough that Villeneuve has noticed, even if the punters probably haven’t yet. The Paris Opera prides itself on employing only the very best, so there’s simply nothing else for it; Claudin will have to take an early retirement. (Villeneuve is at least generous enough to give Erique a season ticket to the opera along with his pink slip. Fucker.) Most people would have a tidy sum socked away after twenty years on a Paris Opera salary, but Claudin has virtually beggared himself furthering Christine’s career. Despite living like a pauper in a flophouse loft, he hasn’t a sou to his name. Even now, though, the first thing Erique thinks to do is to plead with Maestro Ferretti (Leo Carillo, from Ghost Catchers and Horror Island) to let him put Christine’s next few singing lessons on credit, promising the teacher that he’s got a major windfall headed his way any day now.

What Claudin means is that he’s written a concerto, based on the melody of a lullaby from his native Provence. For a while now, he’s been in negotiations over its publication with the firm of Pleyel & Desjardines, and if he can light a fire under the printers’ asses now, all his money troubles should be solved for the foreseeable future. What Claudin doesn’t realize is that the reason it’s been taking so long is because the partners are at loggerheads over whether or not to buy his music at all. Pleyel (Miles Mander, from Fingers at the Window and The Scarlet Claw) is a miserly grump who hates taking chances on unknown composers, while Desjardines (Paul Marion, of The Ghost Ship and The Catman of Paris) thinks the piece has real potential. When Claudin drops by the print shop that morning, the three personalities in play come together in the most disastrous manner possible. Pleyel keeps Claudin waiting all day long, just to be a dick. Claudin, in no mood to be jerked around on this of all days, finally barges into the “employees only” precinct of the shop, determined to make the publishers face him. At that very moment, in the piano studio where the publishers evaluate submissions, Desjardines is showing off Erique’s concerto to no less a personage than Franz Liszt (Fritz Leiber, the father of that Fritz Leiber, from Samson and Deliliah and Cobra Woman). Claudin overhears Liszt playing his music, puts that together with the runaround he’s been getting from Peyel, and leaps to the entirely plausible conclusion that the publishers intend to screw him by sneaking his work into print under a house pseudonym. Erique lunges at Peyel and strangles him to death, but is chased away when one of the publisher’s employees hurls a tray of engraver’s acid into his face. His flesh bubbling and suppurating, Claudin flees the shop, spends the next several hours dodging the police, and ultimately slips away into the sewers to begin a new life as an urban troglodyte.

It’s hard to tell how much time is supposed to pass between that turn of events and the next one, but it can’t possibly be long. Something between a few days and a week or two at the outside. And in that time, Claudin manages to find the subterranean passageway from the sewers of Paris to the lowest sub-basement of the opera house, to select a forgotten space in that sub-basement in which to make his lair, and to pilfer from the opera’s storerooms all the supplies that he’ll need to render it fit for human habitation. He also steals a costume and a mask— and yet not one person, from the opera’s shithead owners (J. Edward Bromberg, from Pillow of Death and Invisible Agent, and Fritz Feld, of Promises, Promises!) to Inspector Daubert himself makes any connection between the rash of odd petty burglaries and the wanted killer with only half a face who used to work at the opera just a short while ago. Instead, people—which is mostly to say the owners’ even more shitheaded sidekick, Vercheres (Steven Geray, from Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter)— begin spreading rumors of a ghost having taken up residence in the building. Daubert doesn’t think to connect that with Claudin, either. So when Biancarolli is suddenly incapacitated by a glass of drugged wine halfway through a performance, giving the director no choice but to put Christine on in her place, suspicion falls first and hardest on Anatole Garron. Let’s give Daubert this much credit, though: presented with an obvious opening to eliminate his rival, he prefers instead to do his job in a conscientious manner, no matter how much that might annoy the jealous prima donna. Then again, Biancarolli’s accusations, if taken seriously, would implicate Christine, too, so maybe he’s got an ulterior motive after all.

Claudin makes things easier for the suspect not-quite-a-couple when he starts leaving notes in the owners’ offices threatening violence if Christine doesn’t start getting some proper starring roles. He shows that he means it, too, by murdering Biancarolli in her dressing room when she stubbornly goes on clinging to her position as the opera’s female lead. That at last gets Daubert and Garron alike thinking about the vanished violinist, since Erique’s arrangement with Ferretti has come to light by this point. Each of Christine’s suitors hatches a plan to flush the Phantom out, hinging in one way or another on his two known obsessions. The inspector wants to make a big damn deal of replacing Biancarolli not with Christine, but with a brassy Italian dame called Lorenzi (Nicki Andre), essentially daring Erique to make trouble, and counting on the scores of police officers who’ll be concealed among the cast, crew, and audience to make the collar. Garron, on the other hand, proposes to bring in Franz Liszt to play Claudin’s concerto, on the theory that the Phantom won’t be able to resist coming out to watch the performance.

Neither strategy quite pans out. Daubert accomplishes nothing but to get the giant auditorium chandelier dropped into the audience by the incensed Claudin, who then abducts Christine out of the chorus in the resulting confusion. And although Erique is thrilled to hear Liszt interpreting his masterpiece soon thereafter, he prefers to play along with the performance in the safety of his underground lair, exhorting Christine to join in on lead vocals. That gets us about as close as this movie will ever come to functioning as a proper Phantom of the Opera adaptation, for while Claudin is caught up in the rock, Christine sneaks up behind him close enough to snatch off his mask, providing us with our first really good look at Erique’s post-burn face. Lionel Atwill’s was much better in The Mystery of the Wax Museum ten years before, and this makeup quite simply ain’t shit compared to the face that Lon Chaney gave his Phantom of the Opera in 1925. The unmasking coincides with the arrival of Daubert and Garron, who bring the rickety ceiling of the Phantom’s lair (but strangely not the opera house for which it serves as the ultimate foundation) down on Claudin’s head with an ill-considered burst of indifferently aimed gunfire, but manage to get Christine to safety. And finally, just in case we’ve forgotten during the past fifteen minutes or so that this isn’t a Phantom of the Opera movie, but rather a Nelson Eddy musical that grudgingly deigns to have a Phantom of the Opera in it, we conclude by resolving the remaining legs of the love-polygon plot in a way that forces me to observe once again that Production Code Administration boss Joseph Breen was an exceedingly dense and imperceptive man.

I will admit to harboring a longstanding personal grudge against this version of The Phantom of the Opera, which might interfere with my ability to judge it fairly. As a small child, I was an avid consumer of picture books on the subject of horror and monster movies, and there were few images in any of them that so captivated me as Lon Chaney’s interpretation of the Phantom. So imagine what it was like when The Phantom of the Opera appeared on the TV schedule at last, and it turned out to be this instead. That said, this may be the one Universal horror “classic” regarding which my opinion lines up with the consensus of fandom, since you’ll look pretty far and wide before finding anyone ready to give it more than a half-hearted defense. Even Nelson Eddy thought it sucked when he saw the finished product, so much that he refused to participate in a planned sequel!

What went wrong was the nigh-inevitable consquence post-Laemmle Universal’s attitude toward its big-ticket productions. Bearing always in mind the cautionary example of Show Boat, without which the studio’s new leadership would never have acquired their positions in the first place, they were adamant about spending A-picture money only on an absolutely sure thing. They wanted the most enticing source material, the biggest stars (even if that meant going outside Universal’s stable of contract players), and the broadest possible audience appeal. And on that level, it makes sense to cast Nelson Eddy, the biggest-selling name in the biggest-selling genre of escapist cinema, in a lavish remake of a colossal hit that was just about to reach the optimum age for nostalgia-bait. It’s just that the hit in question was The Phantom of the Opera, a dark and weird adaptation of a dark and weird novel that would inescapably suffer from any attempt to engineer a four-quadrant crowd-pleaser out of it. The only way The Phantom of the Opera could possibly have worked as a Nelson Eddy vehicle was if Universal had stolen a march on Andrew Lloyd Webber, and cast Eddy as the Phantom. And if Carl Laemmle Jr. were still in charge, he might have done just that. But in 1943, the chairman of the studio’s board of directors was John Cheever Cowdin, who had been a banker before he was a studio head, and would always be a banker at heart no matter what title was stenciled on the window of his office door. Bankers don’t spend the money to hire the most popular singer on Earth only to hide him behind monster makeup and a mask! Nor do they hire him only to have him play second fiddle to a murderous freak. If Eddy was to be the star, then under no circumstances could the Phantom be allowed to steal the spotlight away from him.

In practice, that meant that anything much resembling Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera had to go. In both the novel and the previous film adaptation, the Phantom is neither villain nor love interest, but tragic antihero— and altogether too compelling a figure not to overshadow the kind of personality-free romantic lead that 1940’s Hollywood preferred. He was born monstrously deformed, and if he is now also a monster in the moral sense, we can forgive him because of the profound psychological damage he must have suffered throughout his life. He lives in the catacombs beneath the Paris Opera because he is too hideous to live anywhere else; the employees of the opera know him as the Phantom because he has been there for decades, using his great innate intelligence and his intimate knowledge of the building’s internal layout to mythologize himself as something more than natural, protecting himself from the hatred of those not like him by playing upon their fear of him. He has loved Christine since she first appeared at the Opera, and he has spent years ingratiating himself to her by teaching her to out-sing any rival she may ever acquire. We thus understand what the Phantom is thinking when he hopes that Christine could love him despite his horrid appearance and bizarre lifestyle, even if we recognize that he’s crazy for imagining it.

The 1943 Phantom, in comparison, has no such complexity, and worse still for the movie’s total effect, his new origin prevents him even from making sense as a character. This Phantom is, for all practical purposes, a Batman villain. (Come to think of it, he shares his revised origin almost exactly with Gotham City’s evil ex-district attorney, Harvey “Two-Face” Dent… and considering that the first Two-Face story went to print in October of 1942, it isn’t entirely out of the question that the resemblance is no coincidence.) He has One Bad Day, goes homicidally mad, and turns to a life of gimmick-laden crime rooted in an obsession that he lacked the courage to act upon back when he was sane. However, director Arthur Lubin still wants us not merely to have pity on him, but to have the same kind of extravagant, capital-R Romantic pity that the book and the silent film evoke, and it simply doesn’t work. In those versions, the Phantom’s hopeless love for Christine is pitiable in spite of the enormities he commits in service to it, because it is truly and irredeemably hopeless— nobody’s getting damp in the drawers over a guy with a skull for a face. But Claudin’s love for Christine is hopeless only because he was too chickenshit to make a play for her even before half his face got burned off by that tray of acid. Furthermore, the sacrifices that Erique makes on Christine’s behalf are so extreme that it’s hard to take him as anything less than completely nuts from the word go. I should point out, though, that the latter defect at least is an artifact of clumsy script-doctoring. The Phantom of the Opera had been shambling around Development Hell since 1935, and in a previous draft of the screenplay, Christine was the Phantom’s daughter rather than the object of his unrequited romantic fixation. Once you know that, it becomes immediately obvious that whole scenes were carried over virtually unaltered, irrespective of the effect on Erique’s characterization. No reference to superseded script drafts can help the problem of Claudin’s short tenure as the Phantom, however. Nobody, no matter how resourceful, could build up a bogus legend around himself in so little time, and insisting that Claudin has done so anyway just makes all the other characters look like a bunch of idiots.

What ultimately wrecks The Phantom of the Opera beyond hope of salvage, though, is that it was never seriously intended to be The Phantom of the Opera in the first place. For all the ink I’ve just spilled grousing about what this version does to the Phantom himself, what’s even more damning is that he’s just barely in the movie. Claudin doesn’t have his mishap with the acid until the film is half-over, and he remains largely an offscreen presence until the climactic abduction sequence. Indeed, the mere fact that Christine’s kidnapping now triggers the climax is indicative of how little Phantom we get this time around. It wouldn’t be at all surprising that Claude Rains is so negligible in the role, were it not for the fact I’ve seen him utterly dominate a film in which he is literally invisible for most of the running time. What we get instead is what the producers were really paying for: opera scene after opera scene after Jesus Fucking Christ, another opera scene! Obviously it would be foolish to make a film on this premise without spending some time in the auditorium of the Paris Opera, but I point you toward the Hammer remake another twenty years after this one to see what the balance ought to look like. Nobody who buys a ticket to The Phantom of the Opera wants to see fucking Balalaika or The Girl of the Golden West, okay? Nobody has ever been like, “Hear me out… What if, instead of watching the gross, creepy weirdo with the fucked-up face scheme to turn a girl into his personal sewer-dwelling dungeon diva, we just had her normal-looking drip love interest belt out random bits of opera for, like, a third of the run time?” Or at any rate, nobody ever said that except the producers of this incessantly squawking turkey.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact