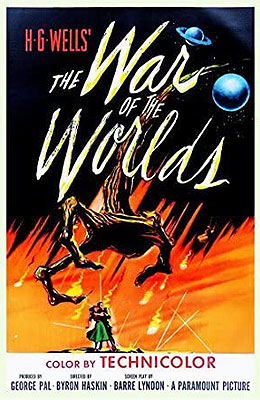

War of the Worlds (1953) ****½

War of the Worlds (1953) ****½

Ask just about anybody to tell you the first thing that pops into their heads about 1950’s sci-fi movies, and I bet you you’ll get something to the effect of “low budgets” or “crappy special effects” or “guys in cheap rubber suits knocking over model train set scenery.” The thing that most people fail to realize, though, is that there is an entirely understandable reason for the tawdriness of nearly all 50’s science fiction movies from America, and that that reason hinges, to a great extent, on the fate of three movies that do not remotely fit the paradigm. Those films are Forbidden Planet, This Island Earth, and this movie, War of the Worlds. The first thing anyone with even the dimmest powers of observation will notice about this triumvirate is the fact that they were all filmed in Technicolor, at a time when nearly every other science fiction or horror film was being shot in black and white. Slightly less obvious, but even more important, is the sheer number of special effects shots that appear in these movies. Both This Island Earth and Forbidden Planet take place almost entirely within more or less intricately constructed, futuristic sets, while easily half of the footage in War of the Worlds involves the Martian invaders or their machines in some way, and much of it also includes non-stock-footage film of what was then still front-line military hardware. Ultimately, all of this boils down to a fuck of a lot of money. In the case of War of the Worlds, the special effects budget alone was something on the order of one-and-a-half million dollars-- one-and-a-half million 1950’s dollars! In fact War of the Worlds actually won the 1953 Oscar for special effects (making it probably the first movie I’ve yet reviewed that ever won any kind of award for anything). The other thing that all three of theses movies have in common is the fact that none of them came anywhere close to making back the money that was spent on them until many years worth of TV syndication royalties and semi-regular revival-house screenings finally pushed their balance sheets into the black. War of the Worlds and company didn’t exactly crash and burn at the box office, but the losses the studios took on these movies were instrumental in convincing the powers that be in Hollywood that A-level science fiction movies were a colossal waste of money, and they would not be persuaded otherwise until the huge success of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes in 1968. In the intervening years, the genre was almost exclusively the province of the B-studios and a low-budget, low-risk training-ground for young filmmakers at the majors.

Kind of perverse, huh, that a movie that is now an almost universally acknowledged classic would have been the first nail in the coffin of big-budget sci-fi in the 1950’s? But that’s basically how it worked. Chances are, you’ve already seen this movie, so a detailed plot synopsis seems a bit silly, but what the hell? As you are probably aware, War of the Worlds is based on the 19th-century novel of the same name by renowned sci-fi big-shot H. G. Wells. In what was probably a sensible move, the filmmakers decided to update the setting of Wells’s book to the present day (well, it was the present day when the movie was made...) in order to preserve the feel of the novel, if not the details of the story. After all, War of the Worlds wasn’t a period piece when it first appeared on the printed page, so to make a film version that was would arguably mean changing the story more than recasting it for the mid-20th century would (and hey, if the movie broke the bank as it was, imagine how much more expensive it would have been to try to combine all those special effects with period sets and costumes). After a brief voice-over introduction (which seems to provide an interesting snapshot of what astronomers thought in the early 50’s), the movie gets down to business. On a beautiful summer evening, the sort on which it seems that nothing could possibly go wrong, an enormous meteor falls in the hills around a small southern California town. Later, it will turn out that this is only the first of hundreds the world over, but for now, it seems to be just an isolated curiosity. And it certainly is curious. To begin with, it’s huge, but it scarcely leaves a crater at all, and there is something odd about its trajectory to the surface-- almost as if it were being controlled.

It is thus understandable that the meteor attracts quite a bit of attention. All the local authorities show up at the crater the next morning (they immediately start talking about the logistics of turning the meteor into a tourist attraction-- this is southern California, after all), along with a famous astrophysicist (played by an almost absurdly virile-looking Gene Barry) named Dr. Clayton Forester (MSTies take note!), and such minor dignitaries as the local pastor and his niece, Sylvia Van Buren (Ann Robinson, sporting some truly surreal early-50’s hair). It is Forester that puts a damper on the mayor’s hopes for financial exploitation of the meteor when he notices that it sets off his Geiger counter (a sure sign that extra-terrestrial intelligence is afoot, that), and advises that people be kept away from the big rock by police deputies. Everyone then goes back into town-- it’s Saturday, and there’s a square dance tonight!

That square dance turns out to be just about the last normal thing that happens anywhere on Earth. While the townspeople are living it up, the three deputies guarding the meteor notice that part of it is unscrewing. Shortly thereafter, something emerges from the meteor that looks a bit like a mutant goose-necked lamp. It casts about, apparently surveying its surroundings, then comes to rest pointed at the deputies (who have concluded, correctly, that it is a machine from another world, and who are attempting to hail its operators, if any) and disintegrates them, their cars, and most of the nearby foliage with a shower of orange sparks. At just that moment, every electronic device in the town goes dead. (You know what that means-- electromagnetic pulse! The Martian heat-ray is nuclear-powered!) Dr. Forester, who knows an EMP when he sees one, uses a compass to trace the pulse to its source-- the meteor, naturally-- and he then rushes to the scene in the company of the local honchos and Sylvia, for whom he is developing the hots. When the Martians respond to the presence of more people by attempting to barbecue everything in sight, our heroes rightly conclude that they are outclassed, and alert the nearest military base to the situation.

The military finds itself just as outclassed. By now, identical meteors are falling like rain as far away as India, in a predictable pattern-- three “landing craft” to an area, three heat-ray machines to a “landing craft.” From this point on, War of the Worlds is almost non-stop ass-kicking, with the Martians’ gorgeous, bronze-hulled, art-deco war machines melting and disintegrating everything in their paths, while the situation becomes increasingly desolate for us humans. Armies are routed, cities are destroyed (the fall of Los Angeles is particularly well done), and A-bombs are dropped to no avail. In between the scenes of carnage, the movie makes surprisingly good use of its characters, never losing sight of the fact that the global crisis postulated by the film has a human dimension. War of the Worlds also wisely avoids showing us too much of the Martians themselves; the creature costumes are not nearly as good as the model war machines or the optical effects associated with them, and if we had to spend as much time looking at them as we do in, say, Invaders from Mars or Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, it might have done this film quite a bit of damage. The best thing about War of the Worlds, though, is probably the fact that humanity is not saved at the last minute by some whiz-bang high-tech gizmo. We are saved, of course, and it is pretty much the last minute of the movie when it happens, but no gadgetry of any kind is involved. I won’t say just what happens, on the off-chance that I’m dealing with the last person alive who’s never seen the movie or read the book, but it works as well today as it did in 1953, or for that matter, in the 1890’s. Unfortunately, the best part of the movie is followed in short order by the worst part, the cloying note of religious piety on which the film ends. It’s not enough to hurt War of the Worlds too badly, but in my estimation, it does cost the film the fifth star which it could otherwise have earned without even working up a sweat.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact