This Island Earth (1955) **½

This Island Earth (1955) **½

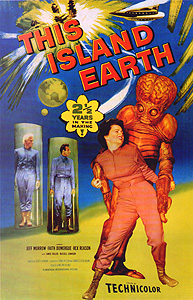

Of the handful of big-budget science-fiction movies that were made in Hollywood during the early-to-mid-1950’s, Universal’s This Island Earth was one of the first— if not the first— to get underway. At a time when most sci-fi films were being slapped together in a month or less, This Island Earth spent some two and a half years in the incubator, the earliest pre-production work having begun in 1952. The studio’s marketing department made sure everybody knew how much effort went into this movie, too— hardly a one of the several designs for posters and print advertisements was without a little atom-shaped seal in the corner reading “2½ years in the making!” As it happened, however, that come-on wasn’t nearly powerful enough, even when combined with a huge picture of the wondrously grotesque monster that became This Island Earth’s best-remembered feature, and the film was a box-office failure. What’s more, history has not redeemed its reputation to anything like the extent enjoyed by the decade’s other A-level sci-fi money-pits. While War of the Worlds, Forbidden Planet, and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea are now generally accorded at least some degree of classic status, This Island Earth wound up being mocked by Mike and the ‘Bots in Mystery Science Theater 3000: The Movie. And although that level of scorn was hardly deserved, neither does This Island Earth merit a particularly vigorous defense against it.

We begin by meeting the world’s smoothest scientist, nuclear physicist and electronics expert Dr. Cal Meacham (Rex Reason, from The Creature Walks Among Us). Just how smooth is Meacham, you ask? Well, he’s cool enough that Lockheed has given him his own T-33 (the unarmed, two-seater training version of the F-80 Shooting Star) on a sort of personal lend-lease, and the way I score it, that’s at least a 40-ounce of smooth right there. Meacham has just finished up with some conference or other, and he’s itching to get back to his real work, which centers on synthesizing uranium from lead in order to increase the available supply of fissionable material for nuclear reactors. After jawing for a while with some reporters, he climbs into his jet and zips off to his federally funded laboratory, deep in the desert of the American Southwest— he almost doesn’t make it. Not far from the lab’s landing strip, the T-33 inexplicably stops responding to the controls, but it is arrested in mid-crash by some kind of energy field, which steadies the aircraft and brings it in for a safe, soft landing. Nor is that the only curiosity which confronts Meacham upon his arrival. His partner, Dr. Joe Wilson (Robert Nichols, later of Westworld and God Told Me To), had been continuing the research in Meacham’s absence, but had succeeded only in burning out a vital piece of equipment. The parts that came in response to Wilson’s requisition for replacements, rather than being the big, bulky gizmos to which he was accustomed, took the form of two tiny, bead-like objects. Yet when Meacham and Wilson test the new parts out, they prove to be far more effective than the versions they had been using before. What’s really peculiar is that headquarters has no record of ever receiving Wilson’s supply order, raising the question, where the hell did the superior new parts come from?

The answer to that question comes the next morning, when a courier arrives with a catalogue from an electronics company neither Meacham nor Wilson has ever heard of. The little bead-like conductors are listed on an early page, but most of the gear in the catalogue pertains to something called an “interociter”— Meacham and Wilson have never heard of one of those, either. His curiosity piqued as much by the sensation that somebody is playing games with him as it is by the unfamiliar equipment listed in the mysterious catalogue, Meacham decides to place an order for everything he would apparently need to build an interociter of his own. The gear comes just days later, and the delivery invoice lists no charge, despite what must be the enormous cost of both the equipment and the delivery, and the two scientists set to work, more baffled than ever. As Meacham and Wilson discover after they finish, an interociter is a something very much like George Orwell’s telescreen, and as soon as they have the thing plugged in, they are greeted by a man with bushy, white hair and a strangely-shaped forehead, who introduces himself as Exeter (Jeff Morrow, from Kronos and The Giant Claw). Exeter tells Meacham that he is the head of an organization of scientists who have dedicated themselves to ending war by using advanced technology to eliminate its root causes— and we may surmise that the mysterious tractor beam which pulled Meacham’s jet out of its crash was a sideline product of their research. Exeter knows of Meacham’s work, and he hopes to persuade him to join the team; assembling the interociter is the entrance exam, as it were, and Meacham has passed with flying colors. If the professor is interested, a plane belonging to Exeter’s group will be landing at the lab tomorrow morning, just before dawn. It will remain on the ground for five minutes only, so Meacham had better do all of his soul-searching the night before. Exeter professes confidence that Meacham will sign on, and then the interociter self-destructs after incinerating both the parts catalogue and the blueprints with some sort of directed-energy beam. The strange man’s confidence is well founded, and when the remotely-piloted DC-3 lifts off early the next morning, Meacham is aboard in the passenger compartment’s single seat.

The person who greets Meacham when the robot airliner sets down is Dr. Ruth Adams (Faith Domergue, of Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet and The Atomic Man), whom he believes he has met before. In fact, Meacham thinks he and Dr. Adams had an abortive week-long romance during a conference in Vermont a few years ago. Adams says he’s got the wrong woman, however, although she does believe they might have crossed paths momentarily at a similar function in Boston. Meacham knows she’s lying, but it will be another day or two before it becomes apparent why. Actually, Adams is far from alone in putting up a smokescreen for Meacham’s benefit; in fact, you’d be hard pressed to name a single person whom the scientist meets on his first day at “the Club” who doesn’t seem to be hiding something. Exeter’s line about finding technological ways to render warfare obsolete is obviously 24-carat bullshit (Robur the Conqueror aside, peacenik eggheads aren’t exactly known for spending their time inventing super-weapons like Exeter’s neutrino ray), and there has to be a reason why Ruth Adams, Steve Carlson (Russell Johnson, of It Came from Outer Space and Attack of the Crab Monsters), and all the other scientists act like they’re terrified of the boss’s assistant, Brack (Lance Fuller, from Voodoo Woman and The She-Creature), who has the same white hair and huge, wrinkly forehead as Exeter. Would you believe the true story is that Exeter and Brack are really aliens from the planet Metaluna, who have been sent by their ruler, the Monitor (The Thing’s Douglas Spencer), to recruit— by force, if need be— the best and brightest physicists on Earth to aid them in their all-out war against the Zagons? Metaluna is on the defensive and losing fast, its people’s only remaining line of defense the nuclear-powered shield that surrounds the entire planet, deflecting the remote-controlled meteors the Zagons use as strategic bombardment weapons. (Say… do you suppose Reiji Matsumoto ever saw This Island Earth?) The enormous amount of power that shield consumes is such that Metaluna is almost out of uranium, while the attrition from many years of high-intensity warfare is such that Metaluna is also almost out of scientists, and that’s why the Monitor wants to pick the brains of Earthlings like Meacham and Adams, whose work promises to make radioactive heavy metals a renewable resource. The aliens are split into two camps regarding the best way to obtain the humans’ cooperation, however. Exeter believes the only viable approach is to treat the borrowed scientists as equals, and to deal with them in the spirit of trade. Brack and the Monitor, on the other hand, want to subject Meacham and company to a form of electronic mind-control, and make an end-run around the whole problem of trying to elicit the humans’ trust. (This is why Adams and Carlson tried so hard to give Meacham the runaround on his first day— they knew Exeter and Brack were up to something fishy, and they were afraid the new recruit might already have been brainwashed.) The latter faction seems to be gaining the upper hand right about the time that Meacham, Adams, and Carlson decide to try their luck at escaping, so it’s a fortunate break for them, in a sense, that the situation on Metaluna has now become so desperate as to render the debate mostly irrelevant. Exeter is to return home, bringing Meacham and Adams with him.

Alas, it is here that any pretense toward actual storytelling on the filmmakers’ part goes right out the window, and from the time the Metalunan ship lifts off until the fade to the closing credits, This Island Earth has nothing much to offer except simple spectacle. In its defense, the combination of sets, props, and matte paintings used to create Metaluna works stunningly by the standards of the mid-1950’s, and the movie’s eye-candy appeal is great enough that a first-time viewer might not notice until after the fact that nothing much goes on during the second half of the film. What does go on, meanwhile, involves the two captive scientists only tangentially. In a rather striking throwback to the fantasy shorts of the silent era, Meacham and Adams just kind of wander through their time on Metaluna, listening as Exeter explains that the years of constant meteoric bombardment have forced his people below the surface of their world, looking as their alien host points out all the really nifty stuff to be seen in the background, and occasionally cowering as one of the hideous insectoid mutants (which Jeff Morrow amusingly pronounces “mute ants”) inexplicably turns mean on them. By the time Exeter bundles his captives back into his ship to return them to Earth, they have done nothing to reset the balance in the war between Metaluna and Zagon, and even their own escape has come about through no action on their parts. As soon as the setting shifts from the country mansion housing the Club, Meacham and Adams become nothing more than spectators to their own adventure. Even more than the top-heavy technobabble, the undignified giant foreheads on the aliens, or the occasional dialogue stinkbomb (Ruth Adams explains how the cat at the Club got its name: “We call him Neutron because he’s so positive!”), it’s that crumbling of the narrative after the halfway point that I think accounts for why This Island Earth is known better today from stills reproduced in books about old sci-fi movies— or from toys and model kits depicting one of the mutants— than it is from actually being seen. It’s a beautiful film, but its beauty is of an empty sort. The movie gets so caught up wallowing in wonders that it seems to lose track of its purpose, regressing into a cinematic style that was obsolete already a quarter of a century before its time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact