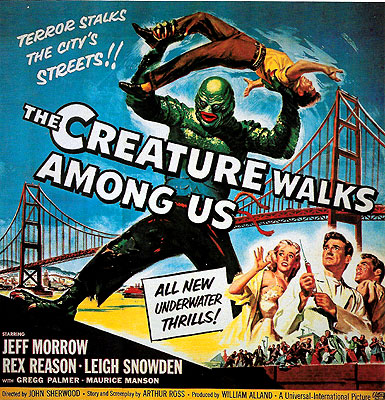

The Creature Walks Among Us (1956) **

The Creature Walks Among Us (1956) **

Universalís third gill-man movie represents a very slight improvement over the slipshod Revenge of the Creature. Itís still a pretty weak movie, especially in comparison to the original Creature from the Black Lagoon, but at least this time the filmmakers had a halfway interesting idea to work with. Sure, that idea constitutes one of the most bald-faced examples of grasping at straws Iíve ever seen, but it still beats the gill-man-at-Sea-World plot from the last film.

As you may recall, when we last saw the gill-man, he was being gunned down on a Florida beach by a squad of rifle-wielding policemen. Though no explanation is offered this time either, this second report of the monsterís death proves to be just as highly exaggerated as the last one, and yet another bunch of scientists have hired yet another boat to take them hunting for him. The mastermind behind the operation is an asshole mad surgeon named William Barton (Jeff Morrow, from This Island Earth and The Giant Claw). His team consists of geneticist Thomas Morgan (Rex Reason, another This Island Earth alumnus), a pair of biologists named Borg (The Undeadís Maurice Manson) and Johnson (James Rawley, who would resurface some 20 years later in The Car), and a professional hunter named Jed Grant (Gregg Palmer, of From Hell It Came). Just for good measure, Barton has brought along his cute blonde trophy wife, Marcia (Leigh Snowden)-- one suspects the man has done his homework, and knows that the gill-man has a weakness for young women in white bathing suits. Grant assesses the situation between Barton and his wife immediately, and with uncanny accuracy: after the girl provokes a fit of annoyance from the surgeon by shooting sharks from the deck of the boat while the rest of the cast are down below, Jed says to her, ďYour husband must be very rich to afford... well... everything he owns...Ē Marcia seems to get the hint, and most of the human drama of the movie hinges on Bartonís borderline-psychotic jealousy of Dr. Morganís friendly interest in Marcia on the one hand and Jed Grantís more avowedly predatory interest in her on the other.

Most of the movieís running time, however, is spent on the hunt, capture, and transportation by boat to San Francisco of the gill-man, which is unfortunate, as the whole process involves very little action. The monster and the boat chase each other around the Everglades for a while, and when the water finally gets too shallow for the boat to go on, Grant and the scientists continue the pursuit in a dinghy. With the odds thus evened, the gill-man makes his move, but he accidentally sets himself on fire when he tries to bludgeon Dr. Morgan to death with a five-gallon can of gasoline. Between the massive third-degree burns and the two hits from Grantís tranquilizer spear gun, the monster proves rather easy to get aboard the big boat, where Barton attempts to treat his burns.

But thereís just one problem-- the creatureís gills were completely burned away, and he is now slowly suffocating. Heís suffocating so slowly, however, that it occurs to the scientists that he must have a set of auxiliary lungs, and subsequent x-rays of his chest confirm their speculation. The lungs are mostly deflated, and they are closed off by muscular flaps, but theyíre there, and Barton sets to work immediately to try to inflate them and get them working more efficiently. You see, this is what the surgeon wanted all along, an opportunity to mess with the creatureís anatomy and physiology in an attempt to prove some crackpot theory that organisms are capable of evolution on the individual level, and not just at the level of population or species. Basically, though the movie of course doesnít say so in these terms, Barton is trying to resurrect the ideas of Jean Baptiste Lamarck, a 19th-century biologist who postulated a somewhat more sedate version of the same thing, and whose theories regarding the mechanics of evolution were eventually discarded in favor of Darwinís (though Lamarckís concepts enjoyed a brief resurgence in the Soviet Union, where they struck some kind of chord in Stalinís mind and thus became a part of official scientific orthodoxy in the Eastern Bloc until the old nutcase finally died in 1953). Barton thinks the body of the gill-man, already a sort of transitional organism, offers the best possible test subject for his ideas, and though his fellow scientists may disagree with him, they realize that letting Barton monkey around with the creatureís respiratory system is now the only possible way to save his life. The operation proves to be a success, and when the bandages come off, the scientists are in for an even bigger shock; though the fire burned away nearly all of the gill-manís skin, it turns out the creature had a second skin beneath his scales, and that this ďunderskinĒ is almost indistinguishable from that of a human being! (While Iím at it, Iíd like to take a moment to point out that the new skin and the revamped respiratory system arenít the only changes the creature undergoes between the time he attacks the doctors out in the swamp and the time the bandages are cut away on the trip to California. When he was in his old environment, the gill-man had the trim physique of an Olympic swimmer [which, of course, is exactly what he was under all the foam latex]; when the bandages come off, heís about seven inches taller, and has the build of a Hellís Angel!) The remainder of the boat trip serves to set up two very important points for the future direction of the movie: first, the gill-man doesnít understand that he can no longer breathe underwater; and second, the monster has the predictable hots for Marcia, and doesnít much like the way Barton and Grant treat her.

When the boat reaches San Francisco, and the locale shifts to the grounds of Bartonís isolated country mansion, the focus of the doctorsí work changes as well. Having rebuilt the gill-manís body, Barton now turns his attention to his mind. It is thus unfortunate for Barton that the creature thinks heís just as big a cock as we do, and has become very protective of the surgeonís put-upon wife. Barton might possibly have been able to control the situation if he were in complete control of himself, but with Morgan and especially Grant spending so much time hanging around Marcia, the doctor would prove an even more interesting subject for psychological experimentation than the captive gill-man. One night, after he catches Marcia and Grant swimming together, he throws the hunter out of his house. Grant says something to provoke his erstwhile host on the way out the door, and Barton flies into a rage, pistol-whipping the man to death. Now heís got a problem, but not nearly as big a problem as heíll have when he tries to ďframeĒ the gill-man by dragging Grantís corpse into the sheep-pen where the monster has been confined. In order to open and close the gate, Barton has to switch off the power to the penís electrified fence, and he doesnít have time to turn it back on when the creature decides the time has come to kick some mad scientist butt. The beast knocks down the gate and then chases Barton down in his mansion, destroying everything he touches. (And I do mean everything he touches!) After giving his captor whatís coming to him, the creature lumbers off to the seaside, and the movie decorously cuts to the closing credits before he wades out into the water and, in effect, commits suicide.

It isnít immediately obvious, but the direction the series took with The Creature Walks Among Us was already strongly hinted at in Revenge of the Creature. Though the filmmakers seem to have intended no such thing, the gill-man ends up being far and away the most sympathetic character in the earlier movie. Itís difficult to imagine anybody who doesnít get off on stealing the eggs out of birdsí nests to smash them or burning insects to death with a magnifying glass watching that film and rooting for anybody but the gill-man. I mean, think about it-- one minute, heís out in the Amazon, minding his own business, and the next, heís been knocked unconscious with dynamite, transported thousands of miles from his natural habitat, and chained to the floor of a great big tank, while arrogant scientists stick him with cattle prods and try to force him to learn tricks with which to amuse the unwashed masses of Floridian bumpkinry. In The Creature Walks Among Us, the gill-man has it even worse, but this time, itís clear that the people in charge of the movie realize what a bunch of fuckheads the human scientists-- even nice-guy Dr. Morgan and jolly old Dr. Borg-- must be to have put the hapless monster in the situation they have. Taking him out of his element was bad enough, but rebuilding his body so that he can never return to it is simply unforgivable. Indeed, itís with something close to relief that we watch the monster waddle out onto the beach toward his this-time-inescapable death-- at least this way, they wonít be able to justify a fourth movie in which to torture the poor fucker any more!

All in all, itís an interesting idea for a film, but also a rather desperate one, and that desperation is part of the movieís undoing. The creatureís transformation is too far-fetched to leave so largely unexplained (or rather, to leave supported by so many muddled, inconclusive, mutually contradictory explanations) as The Creature Walks Among Us does. Barton and Morgan spend much of the movie arguing with each other over whose interpretation of events is the correct one, but at no point is it at all clear what either man is talking about. The movieís somnambulant pace doesnít help things any, either. With even as much action as the original Creature from the Black Lagoon, it would be easier to ignore the desperation of the premise and just sit back and enjoy the ride. But instead, the deliberate pacing gives you all the time in the world to think about how little sense the script makes, while the high overall production values stand in the way of appreciating the movie for its illogic, and the plight of the monster makes the movie too depressing to be much fun. It may be an improvement over its immediate predecessor, but youíd still be better off sticking with the original.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact