The Giant Claw (1957) -*****

The Giant Claw (1957) -*****

There’s something essentially, fundamentally different about Asian monster movies, largely because there’s something essentially, fundamentally different about Asian movie monsters. Even when the creature is something relatively pedestrian, like a revived dinosaur or a giant bug, the Japanese and their imitators along the western rim of the Pacific can be counted upon to take a more expansive view of the permissible departures from nature, unencumbered by modern Anglo-Saxon notions of how much disbelief an audience can comfortably suspend. This doesn’t mean that their monster movies are better than ours, but it does mean that kaiju eiga are predictably weirder than their Western counterparts. The monsters are bigger, faster, stronger, tougher, more anatomically freakish. They have inexplicable powers and anthropomorphic motivations. The destruction they wreak on the human settlements they visit is on a grander, nearly apocalyptic scale. And the films’ creators appear to subscribe wholeheartedly to Arthur C. Clarke’s famous dictum that technology becomes indistinguishable from magic beyond a certain threshold of advancement, cannily assuming further that for the average person, that threshold was crossed sometime around 1945. I bring all this up here, in the context of a notorious Hollywood monster flick made with no Asian involvement whatsoever, because what makes The Giant Claw truly special, beyond its ludicrously inept dialogue, its impressive misuse of stock footage and voiceover narration, and its legendarily cheap and unconvincing special effects, is that it boldly defies the aforementioned pattern. The Giant Claw is every bit as unrepentantly bizarre as any Japanese or Korean creature film, and in exactly the same characteristic way. It is, so far as I’ve seen, the only true American kaiju movie.

The opening is going to look awfully familiar. Fear not, though— sure, it covers the same material (and may even use some of the same film clips) as the leaden stock-footage intro to Universal’s contemporary The Deadly Mantis, but this picture will shut its fucking mouth about polar radar pickets long before the seven-minute mark, I promise you. Once again, the reason behind all this attention devoted to aerial early warning systems is that we need some plausible excuse for why these people in particular would be the ones to make first contact with a giant monster, and we are quickly introduced to a small team of electronics experts that includes our main protagonists, electrical engineer Mitch McAfee (Jeff Morrow, of Kronos and Octaman) and mathematician Sally Caldwell (Mara Corday, from The Black Scorpion and Tarantula). Today’s order of business is the calibration of a newly installed radar rig, and McAfee is zipping around in a jet that will be represented by stock footage of about four distinctly different aircraft over the course of this single scene, while Caldwell, station commander Major Bergen (Clark Howat, of Earth vs. the Flying Saucers), and an unnamed radar technician attempt to make the air search gear interpret his speed, bearing, and altitude correctly. While they’re at it, something huge— nay, something “as big as a battleship”— flies by McAfee’s plane at incredible speed, and a Stentorian 50’s Narrator inexplicably bursts in to describe the action of the next few minutes, even as we watch it unfold before our eyes. (That Stentorian 50’s Narrator will return for several similar interruptions over the course of the film.) None of the ground-based radars picks up any trace of the giant UFO, nor does the radar that may or may not be aboard McAfee’s jet, depending on what he’s supposed to be flying in any given shot. The engineer insists that he saw something through the cloud cover, however, and on the theory that it is better to freak the fuck out than to be sorry where national defense is concerned, Bergen orders a squadron of fighters aloft to search for the mysterious bogey. Bergen is in a bad mood when McAfee lands, for none of those pilots found anything, and one of them has gone missing. The major is convinced that McAfee (who has a reputation for “kind of making his own rules”) is playing a prank on his military colleagues, and he’s furious that the engineer, as a civilian, is beyond the reach of military discipline. Bergen settles down a bit, though, when he gets the phone call announcing the discovery of the missing plane. It’s been destroyed and its pilot killed, but that news comes bundled with a report that another plane went down in the vicinity, the crew of which also radioed in a sighting of an invisible-to-radar UFO in the moments before their crash. (The countdown to everybody but McAfee’s forgetting the significance of that last detail begins… now.)

McAfee and Caldwell are finished with their work up in the Arctic, and an Air Force transport takes off to fly them to New York. They end up facing an unexpected layover when— that’s right— a UFO that doesn’t show up on radar buzzes their plane over the Adirondacks, and tears up one of the engines. Pilot and passengers alike survive the crash, but the former is hurt badly; luckily, the transport crashed not far from the farm of Pierre Broussard (Louis Merrill), a Quebecois immigrant who takes them all in and keeps Mitch and Sally well lubricated with homemade applejack while they wait for the authorities. The applejack also helps McAfee swallow his rage when he receives a phone call from Bergen’s superior, Major General Van Buskirk (Robert Shayne, from War of the Satellites and Indestructible Man), who (what did I tell you?) insists that he has to be pulling the Air Force’s collective leg, on the grounds that local radar showed nothing in the sky save McAfee’s own plane at the time of the crash. Let us simply observe that it is a committed practical joker indeed who’ll send his DC-5 into a death-dive for the sake of a good gag, and leave it at that. (Well, alright. Let’s also observe that a guy with a name like VAN BUSKIRK— pronounced “Buzzkirk”— ought to be blasting about with a jet-pack and a raygun, punching diabolical outer-space Chinamen in the face, not sitting behind a desk, pooh-poohing UFO reports while his arteries harden and his muscles turn to mush.) Anyway, about the same time that the cops and paramedics arrive to collect the now-dead pilot, Pierre hears some commotion out at his cattle pen, and goes to check it out. He returns to the house in a panic, raving about having seen “La Cacagna,” a legendary Quebecois chimera with the body of a woman, the head of a wolf, and wings of indescribably vast span— an omen of impending death for anyone who lays eyes on it. Now you might think that McAfee— who, let us not forget, has been seeing quite a few humongous and unclassifiable things in the air himself lately— would have a bit of sympathy for Pierre at this point, and might indeed be sharp enough to make the inference that both of them have observed the same phenomenon, interpreting it differently according to their respective experiential frameworks. Mitch will be happy to disappoint you, however. In fact, he scoffs even harder at Pierre’s Cacagna than Bergen and Buskirk had at McAfee’s UFO.

He does something even smarter upon arriving in New York, too, climbing aboard yet another airplane with Sally. This time luck is with them, though, and their flight is the only one we’ll see in The Giant Claw’s complete running time that has no encounter with any battleship-sized flying whatsists. Mitch and Sally pass the time first by launching the obligatory romantic subplot (some of the dialogue that advances it is almost clever, by the way, even if it bears no recognizable resemblance to anything real people might actually say), and then by getting into a huffy argument over McAfee’s interpretation of the pattern formed by the locations of the UFO-connected crashes— which now number five according to a quick consultation with today’s newspaper. Caldwell doesn’t raise the obvious objection that a spiral could be drawn to connect virtually any scattering of random data points, but harps instead on the impossible speed that would be necessary for the same airborne object to have accounted for all five incidents. It takes the intervention of the man in the seat behind Mitch to make the two love-birds abandon their bickering and resume sucking face.

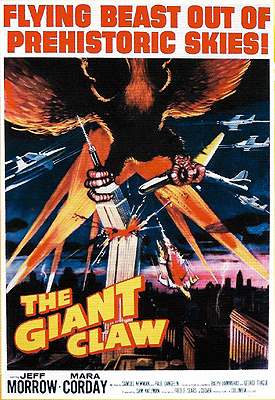

Meanwhile, there’s a team of Civil Aviation Board investigators on the way to look over the wreckage of McAfee and Caldwell’s previous plane, and they too run afoul of the giant UFO. Or on second thought, perhaps that should have been “a fowl,” as this lot enjoy the distinction of being the first observers to get a good look at the thing, and thus also the first to utter the movie’s favorite simile in its fully developed form: “It’s a bird! A bird as big as a battleship!” And what a bird! Columbia Pictures, the company for which The Giant Claw was produced, had close ties with Ray Harryhausen, having already released It Came from Beneath the Sea and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, and supposedly producer Sam Katzman originally hoped that Harryhausen would consent to be his monster-maker, too. Harryhausen didn’t come cheap, though, and Sam Katzman… well, Sam Katzman used to work for Monogram back in the 40’s. He could have given cheap lessons to Roger Corman. So instead of trying to come up with another ten or fifteen grand to invest in Dynamation, Katzman hired some guy in Mexico City to build him a puppet. Nothing I could say would do this puppet justice, either. I could tell you that it’s supposed to be a titanic vulture, but really looks more like a turkey with advanced lymphatic cancer and a bad case of the mange; I could tell you about its googly ping-pong-ball eyes, its flaring nostrils, and its haphazard multitude of snaggly teeth; I could even tell you that it has the same hairdo as Penfold from “Dangermouse.” You still couldn’t imagine how ridiculous this thing really looks. I could say that it would have been perfectly cast as Big Bird’s crack-smoking hoodlum brother in a Very Special Episode of “Sesame Street,” and you would still have an altogether too favorable impression of how credibly former Oscar nominee (and present poor, sad bastard) Ralph Hammeras integrates it with the live-action footage and manipulates it in its attacks on the rest of the movie’s shoddily constructed model-kit miniatures. The Giant Claw’s monster is simply beyond the power of words. And yet everyone who confronts it, beginning with the CAB field team, reacts with such stark, butt-puckering terror that there can be but a single explanation for their behavior— not one person from the cast has actually seen the puppet. They’d all have a hell of a surprise in store come the premiere…

Anyway, the indescribably hilarious demise of the CAB guys finally convinces VAN BUSKIRK! that there’s something to this UFO business after all. Then Caldwell suggests that the high-altitude camera balloons she’s been using for another of her research projects might have photographed the monster, bringing to light the first decisive evidence as to the nature of the Moth-Eaten Peril. Once he sees those photographs, the general responds in the most perfectly 50’s manner imaginable. He declares the whole business top secret, and passes the buck another rung up the ladder of command to Lieutenant General Edward Considine. (Is there a man, woman, or child among you who will be surprised to see that Considine is played by Morris Ankrum, whose other gigs in uniform include The Beginning of the End and The Most Dangerous Man Alive? No, I didn’t think so.) Considine, not one to fuck around, scrambles a flight of interceptors the moment anyone hears so much as a squawk out of the bird; McAfee, Caldwell, and VAN BUSKIRK!!!! all happen to be in his office at the time, and he gloatingly switches his desktop radio to a frequency on which he and his guests may monitor the course of the Great Turkey Shoot of 1957. Of course, what they really monitor is the wholly one-sided slaughter of the interceptor squadron, as the “rockets… cannons… machine guns…” of the fighter planes fail to do any harm whatsoever to the monster, while it gleefully knocks the stock-footage F-80s, F-84s, F-86Ds, F-89s, and F-94s (all of which mysteriously transform into model-kit F-102s immediately before exploding) out of the sky, and gobbles up the plastic army men representing their parachuting pilots.

Obviously a rout like that one means it’s time to call in the White Coat Cavalry, which arrives here in the form of Dr. Karol Noymann (Edgar Barrier, from Cobra Woman and Arabian Nights) of the Research Lab. (Interestingly, this character— but not the actor playing him— would return in screenwriter Samuel Newman’s subsequent Invisible Invaders.) Noymann comes bearing the most astonishing load of faux-physics bullshit I’ve heard in years, explicating the super-power that really lifts the Giant Claw out of the Monster from Green Hell’s league and into Gyaos and Megalon’s. Those bullets and rockets that didn’t hurt the big goony-bird? They never so much as touched it. It has a forcefield, you see— a forcefield made of pure antimatter! This is because the bird, although made of ordinary matter itself, hails from “a Godforsaken antimatter galaxy millions and millions of light-years away.” Noymann further clarifies that the bird can raise and lower its shields at will, enabling it to attack matter-built objects with its beak and talons when it isn’t fending off a volley of rockets or a hail of machine-gun fire. The forcefield also explains why the creature doesn’t appear on radar, for radio waves slip right around it without being reflected. Oh, and the bird’s tissues are composed entirely of elements that are totally unknown to science, and if you subject one of its feathers to spectrographic analysis, the spectrograph will somehow self-destruct in a way that leaves all of its perfectly intact components spread out evenly across the nearest workbench. Wait— what’s that you say? There aren’t any gaps in the periodic table, so naturally occurring elements unknown to science could exist only in a place where the strong and weak nuclear forces were both vastly more powerful than they are in our universe? Radio waves ought to bounce off of antimatter objects just the same as they reflect from ordinary matter? An organism with a material body shouldn’t be able to project an antimaterial forcefield without destroying itself? The forcefield ought to encounter a similar annihilation problem simply from being turned on in an atmosphere? Oh, shut up, you! This is Karol Noymann of the fucking Research Lab talking, here! The outfit he works for is so goddamned important that they don’t even need a name that means anything! His lab coat is way whiter than yours, so you just take your… your… facts and stuff ‘em, you hear?

There is one little question that Noymann hasn’t even attempted to answer yet, though. What imaginable purpose could the bird have in coming to Earth? Sally Caldwell has been wondering about that, and she thinks it’s here to make a nest. Sounds pretty asinine, if you’re asking me, but then again, so does a sea turtle laying its eggs on land or a salt-water fish swimming miles and miles upstream to spawn in fresh water, and yet nature somehow decided that both of those were good ideas… Sally also makes the connection that eluded Mitch earlier, and posits that Pierre’s Cacagna sighting was really the space bird setting down to choose a nesting site. Somebody clearly needs to go back to the Adirondacks and find the creature’s eggs before they hatch! Meanwhile, VAN BUSKIRK!!!!’s brilliant scheme to keep the avian invasion a secret has hit the snag that any idiot could have warned him about, as the monster (being no respecter of security clearances) has finally decided to take its rampage public. The only hope lies in a hare-brained idea of Mitch McAfee’s. Since matter and antimatter annihilate each other when they come into contact, it ought to be possible to batter down the bird’s shield by bombarding it with material particles, leaving the monster vulnerable to conventional attack. (Wait— didn’t somebody say something about that just a little while ago?) For some flagrantly illogical reason that McAfee explains at great length, these particles will have to be muonic atoms (an aside: how the hell does a screenwriter absorb so much legitimate information about muons and muonic atoms while getting so much basic particle physics so drastically wrong?), and that means he, Caldwell, and Noymann are going to have a challenge to rival the Manhattan Project on their hands. Fortunately, a lieutenant general is more than sufficiently high-ranking to authorize such an undertaking, and three scientists laboring unassisted in a two-room laboratory are more than enough to bring it to fruition…

With a movie like The Giant Claw, I’m always strongly tempted simply to describe it, without making any effort at analysis. It is, after all, a tall order to make sense of something so insistently absurd, and to a great extent, a film like this one speaks for itself. In some ways, the difference between The Giant Claw and the run-of-the-mill 50’s Hollywood monster mash is a matter of degree. Other movies have risible premises, lousy dialogue, disgraceful monsters, and so on; this one merely has more of those things, or more extreme versions of them, than the competition. But as I have occasionally observed in other reviews, there is a point beyond which a difference of degree becomes a difference of kind, and The Giant Claw unquestionably stands on the far side of that divide. No other American giant monster movie that I’ve seen (with the possible exception of Kronos) asks its viewers to accept nearly so much utter bullshit with such a completely straight face. I don’t just mean the stuff about the monster’s nature, either. We’re also supposed to believe that despite a radius of operations encompassing the entire globe, Big Bird here invariably manages to show up wherever Mitch McAfee is, any time he tries to do something significant. We’re supposed to believe that Mitch and Sally would keep getting into airplanes even though they know perfectly well that there’s a monster on the loose, destroying any airborne object that crosses its path. Hell, we’re supposed to believe that a civilian electrical engineer— as opposed to, say, an Air Force pilot— would have been up in that test plane in the opening scene in the first place! Then there are the bizarre non-sequiturs, like the quartet of doomed hotrodders (notice that the one girl isn’t even inside the car, really!) whom McAfee and Caldwell encounter after their raid on the bird’s nest in the Adirondacks. They have nothing to do with the story, and there’s no indication that they made it into the advertising campaign as a bid to lure in the teenagers (who, realistically speaking, would surely have turned out to see this movie anyway), so what in the hell are they doing here?! Again, I find myself flashing on later Asian monster flicks, recalling the similarly out-of-place gatherings of reckless youth in Gamera, Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, and Yongary, Monster from the Deep. In the end, though, what distinguishes The Giant Claw is indeed the bird itself and all that it implies. The sight of the stupid thing swooping awkwardly down on a tabletop set with styrofoam landscaping and flying off with an O-scale model train in its talons is the stuff that lifelong crap-movie addictions are made of.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact