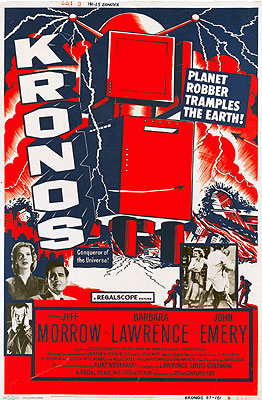

Kronos/Kronos: Destroyer of the Universe (1957) -**½

Kronos/Kronos: Destroyer of the Universe (1957) -**½

So, what’s the goofiest monster you’ve ever seen in a movie? Was it Gabera from Godzilla’s Revenge? Was it Guiron, the 70-meter Ginzu knife in Gamera vs. Guiron? Was it The She-Creature? How about that nearly shapeless green guy with a shovel for one hand and a drill for the other in Infra-Man? All pretty goofy monsters, I grant you, but if any of them are your top pick, then you clearly haven’t yet witnessed the wonder that is Kronos/Kronos: Destroyer of the Universe. The monster in this movie outdoes even Robot Monster’s Ro-Man. What we have here is a kaiju-sized robot whose body consists of (I shit you not) a pair of black metal cubes stacked on top of each other, separated by a stout chrome cylinder, with a shallow dome and a pair of antennae surmounting the upper cube, and an indeterminate number of cylindrical legs projecting downward from the lower one. Pretty amazing, huh? But wait, it gets better: when Kronos “walks,” the lower half of its body becomes a cartoon!!!! Really!

Needless to say, a monster like that can come from only one place. And sure enough, the first thing we see after the opening credits and the obligatory accompanying theramin music is absolutely the most unconvincing flying saucer I’ve ever laid eyes on. Not even the pie-plate saucers from Plan 9 from Outer Space are any worse! This none-too-special effect deploys a tiny glowing whatchijigger as it flies over (of course) the American Southwest, and said whatchijigger proceeds to assume control of a passing motorist’s mind. Under extraterrestrial influence, the driver turns around and pays a visit to an impressive matte painting of an observatory, where he cold-cocks the security guard, sneaks inside, and transfers the hypnotic whatchijigger to the brain of Dr. Hubbell Eliot (John Emery, from Rocketship X-M and The Mad Magician), renowned astronomer and director of the observatory. Having accomplished his mission in both the aliens’ nefarious scheme and movie’s nefarious screenplay, the formerly possessed motorist promptly drops dead of a heart attack.

Meanwhile, two of Dr. Eliot’s subordinates, Dr. Les Gaskill (Jeff Morrow, from This Island Earth and The Creature Walks Among Us) and Dr. Arnold Culver (George O’Hanlon, the voice of George Jetson), have detected the flying saucer, though they don’t yet realize just what it is. As far as they’re concerned, they’ve just discovered a previously unknown asteroid, albeit one that has a mighty peculiar orbit, and it isn’t until they sic their computer, S.U.S.I.E., on it that they begin to suspect anything more. (In case you’re wondering, S.U.S.I.E. stands for “Synchro Unifying Sinometric Integrating Equitensor— that is to say, “The Machine that Exerts a Uniform Amount of Force on Everything It Touches by Calculating a Combined Average for Several Simultaneous Measurements of the Chinese.” What exotic physical and mathematical principles make this remarkable device possible, to say nothing of what imaginable application it might have to the science of astronomy, is anybody’s guess.) And unfortunately for the people of Earth (those of Mexico especially, as we shall soon see), the hypnotic whatchijigger in Dr. Eliot’s brain not only knows what S.U.S.I.E. is capable of, but has the power to scramble her circuits and delay thereby Drs. Gaskill and Culver’s learning the truth about the UFO.

But the scientists were bound to figure it out sooner or later, especially after the spacecraft’s moron pilots decide to draw as much attention to themselves as possible by flying their four-mile-wide vessel straight at the Earth! Remember, the only people on the planet who know about the saucer think it’s an asteroid, so of course an alarm is going to be raised the moment S.U.S.I.E. finishes crunching the numbers related to the ship’s trajectory. A quick call to the pentagon results in the alien craft being pelted with Luftwaffe-surplus V-2’s until it finally crashes into the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Baja California. Gaskill isn’t satisfied, though. His observations of the “asteroid’s” behavior strongly suggest to him that it was being controlled by something other than the laws of ballistics. So he, Culver, and a research assistant named Vera Hunter (Barbara Lawrence, who had been in Oklahoma!, of all things, just two years before) all make the trek down to Mexico in the hope of finding some clue to the saucer’s true nature and origin. After a few days without appreciable success, the scientists are rewarded for their patience when the saucer floats to the surface one evening. It’s gone again when the sun rises the next morning, but it has left a little souvenir behind— that preposterous robot I told you about in the opening paragraph.

While Gaskill and company are hunting UFOs in Mexico, Dr. Eliot is having a hell of a time back home. The rocket attack on the flying saucer did something to the communications link between his parasitic whatchijigger and the aliens, and he now finds himself swinging in and out of their control unpredictably. Much easier to predict is the way the rest of the world responds to Eliot’s “mood swings.” He soon finds himself committed to a mental hospital under the care of Dr. Albert Stern (Morris Ankrum, from Invaders from Mars and Earth vs. the Flying Saucers). Stern doesn’t know what to make of Eliot’s highly unusual EEG readings, but what the astronomer has to say when he’s lucid certainly sounds like the ravings of a madman. It is Eliot’s contention that his mind has been invaded by an alien intelligence from a planet where life takes the form of pure electrical energy. This planet’s energy reserves are dwindling fast, and so all life there faces extinction in the very near future. In order to avert this catastrophe, the aliens have sent “accumulators” out all over the galaxy to search for energy-rich planets to plunder. When these scout “accumulators” find what they’re looking for, they will get in touch with the homeworld, and entire armies of the things will be dispatched to suck the unfortunate planet dry. Chances are you don’t need to be told that the big, stupid robot (or “Kronos,” to use Gaskill’s name for it) is one of those accumulators. Eventually, though, the aliens controlling Eliot decide he’s told his shrink just a wee bit too much, and at the first opportunity, they force Eliot to kill him.

That’s about when Kronos gets down to business. Following instructions from Dr. Eliot, it attacks a power plant in Mexico (shrugging off an attack by the Mexican air force, which is so poorly equipped that it goes after the monster machine with a squadron of P-51 Mustangs!), and absorbs all of its energy. Worse yet, the pilfered power causes Kronos to grow! You’ve all probably figured out what that means, but Dr. Eliot is on hand to explain it all in one of his autonomous interludes just in case. As Einstein teaches us, matter and energy are really two sides of the same coin. Turning matter into energy is comparatively easy— the stars do it wholesale constantly, and a less efficient means to the same end drives nuclear reactors and makes H-bombs possible. Kronos’s creators have learned to do the opposite, turning energy into matter, and what that means is that the military’s big plan for dealing with the giant machine— nuking it— is the very worst idea that a person could possibly think of under the circumstances. Why do you think Eliot is such a big proponent of nuclear attack when he’s under the aliens’ power?

But Gaskill’s desperate efforts to get the airstrike aborted come to naught. The Pentagon calls the bomber home, alright, but not before Kronos has been sighted— and has sighted the bomber in return. And with all those delicious megatons only a few thousand yards away, the monster isn’t about to let them slip through its... well, okay, so Kronos doesn’t exactly have fingers, but still— you get the point. Instead, Kronos uses some of its accumulated energy to magnetize its body, drawing the bomber and its atomic payload inexorably toward itself. When the smoke clears, Kronos is fully double its original size. Having tasted atomic power and found it to its liking, Kronos sets off for a tour of America’s nuclear arsenal, with a short stop for a snack in Los Angeles.

Now obviously, we people of Earth can’t have that, so it’s a good thing Gaskill and Culver are on the case. After going over what Eliot said to them, the two scientists hit upon the idea that Kronos’s energy-conversion process could be interrupted and reversed, and that such a reversal would mean the end for the huge robot, its body literally dissolving away into pure energy. And what’s more, Gaskill thinks he knows just how to do it, even if the explanation he gives his colleagues (and the audience) doesn’t make any kind of sense at all. All you really need to know is that an F-100 Super Sabre drops a canister of what look to be perfectly ordinary fireworks on Kronos just as it is gearing up to drain L.A., and the mechanical titan instantly begins glowing and steaming, until it explodes into a vast mushroom cloud. Los Angeles is saved from certain destruction, Gaskill and Vera are free to get down to the serious business of banging each other, and the people of Earth live happily ever after.

It ought to be pretty obvious why Kronos is such a fun film when you’re in the mood for 50’s sci-fi. Just about every genre cliche in the book is on display: clunky alien technology, electronic mind control, nuclear power, the wanton use of atomic weaponry, computers that fill entire rooms, curiously bumbling men of science, a purely ornamental female lead. If the plot moved a little faster (okay, a lot faster), Kronos would be an instant party. But as is only fitting, the movie’s creators saved the best for last.

It’s been a long time since I’ve felt compelled to don the white lab coat of Dr. Science. After all, most of the movies I’ve reviewed lately have hinged on the supernatural in one form or another, while those that haven’t have concerned themselves mainly with naked girls. And though I’m sure a discursus on the physics of Dyanne Thorne’s breasts would be highly amusing, it just didn’t seem necessary for your understanding of Greta the Mad Butcher. But Kronos... Kronos is another matter. You don’t have to have much of a science background to be alarmed at the prospects for L.A. when Kronos blows itself to bits just outside of town— I mean, the filmmakers used a stock-footage H-bomb blast, for God’s sake!— but if you do happen to have one, this scene becomes one of the sci-fi genre’s great all-time howlers. Allow me to explain...

(And allow me also to apologize in advance for all of the really big numbers I’m about to throw at you. But there’s no other way to make this point, and it will be worth it when it’s all over, I promise.)

As Gaskill explains, the key to Kronos’s destruction is reversing the energy-to-matter conversion process, turning all of the robot’s mass back into energy. That process, as you may recall, is governed by the formula E=mc2, in which “E” stands for energy as measured in joules (1 joule = 0.239 calories), “m” stands for mass as measured in kilograms (1 kilogram = about 2.2 pounds), and “c” stands for the speed of light as measured in meters per second— approximately 297,600,000 mps. Given that Kronos is roughly the size of a Spanish-American War-era battleship, it seems reasonable to conclude that it is comparably heavy— 12,000 long tons (1 long ton = 2240 pounds) would be a plausible estimate. Converting to that figure to kilograms gets us approximately 12,218,000 as our value for m. Multiply that by the square of c, and you get 1,082,096,456,000,000,000,000,000 joules, a number so gigantic as to be completely meaningless to the human mind. Fortunately, there is a way to make this vast quantity comprehensible. Because the joule is such a tiny unit, when most people measure the energy released by very large explosions (those caused by nuclear weapons or asteroid impacts, for example), they generally do so by telling you how much chemical high explosive would be necessary to cause the same effect. The units of choice are usually kilotons (1 kiloton is equivalent to the explosive force of 1000 tons of TNT), megatons (a million tons of TNT), or gigatons (a billion tons of TNT— a unit best suited to asteroid strikes). For an idea of how this works in practice, consider that Little Boy, the atomic bomb that destroyed Hiroshima, had a yield in the neighborhood of 20 kilotons. Given that 1 kiloton = 4,186,800,000,000 joules, we can convert that monster number from the last calculation into the rather more manageable figure of 258,454 gigatons. In other words, when Kronos blows its stack at the end of the movie, it does so with a force equivalent to that of more than 258 trillion tons of TNT! To put that into perspective, the size of the undersea crater left by the asteroid strike that most paleontologists today blame for the mass extinction at the close of the Cretaceous Period (when more than three quarters of all species of life on Earth— including the last of the dinosaurs— disappeared) suggests that the rock which produced it probably hit with a force of 191,793 gigatons— substantially less than my estimate of the power of Kronos’s death-throes! Thus not only would Gaskill’s last-minute eureka! moment not have saved the city of Los Angeles, it would have led, in fact, to the immediate end of civilization and to the destruction of most multicellular life on Earth. Kronos’s happy ending doesn’t seem quite so happy when you put it that way, does it?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact