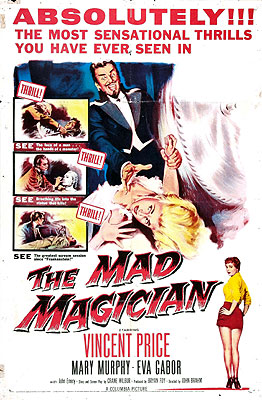

The Mad Magician (1954) **Ĺ

The Mad Magician (1954) **Ĺ

The first thing that struck me about The Mad Magician was how young Vincent Price looked. Yeah, I know-- 1954 was a long time ago. But even so, itís a very strange thing to see somebody at the age of 43 when your first impression of that person was made when he was 30 years older. The fact that Price was an unusually well-preserved 43 only adds to the effect. For the most part (although its story has some implications that I want to discuss at length later), this is just your basic killer-maniac-on-the-loose flick, the sort of movie that would gradually evolve into the slasher film over the next 25 years. And as if you couldnít tell that already, the role of the maniac is played by Price.

Don Gallico is his characterís name, and youíve probably already figured out that heís a magician. Actually, the events of the first scene show that it would be closer to the truth to say that he wants to be a magician. The scene in question depicts Gallicoís first performance ever, during which he means to debut two astounding illusions. To begin with, he plays the first half of the show pretending to be another, rival magician called the Great Rinaldi (the real Rinaldi is played by John Emery, from The Woman in White and Rocketship X-M). As Gallicoís assistant, Karen Lee (Mary Murphy), points out to her boyfriend, detective Lieutenant Alan Bruce (Patrick Neal, who would appear many years later in The Stepford Wives and Larry Cohenís The Stuff), the impersonation is uncanny; not only does Gallico perfectly imitate the other magicianís physical appearance and mannerisms, his mimicry of Rinaldiís voice is so close as to be all but indistinguishable from the real thing. Secondly, in the main body of his act, Gallico unveils a new twist on the old sawing-a-woman-in-half trick, which features the amazingly believable decapitation of Karen by a 30-inch circular saw. Or at any rate, it would have. As it turns out, Gallico never gets to carry out the trick, because at the critical moment, a pair of policemen arrive with a court injunction stopping Gallicoís show. You see, Gallicoís real job is the invention of magic tricks for a company owned by Ross Ormond (Don Randolf, who would go on to play the general in The Deadly Mantis), a company which then sells those illusions to magicians like Rinaldi. According to the terms of Gallicoís contract, Ormond owns any and all of Gallicoís creations, even those that he produces on his own time. Thus, the decapitation trick belongs to Ormond, and thus Gallicoís performance of it constitutes copyright infringement. Isnít the world of entertainment law grand?

To add insult to injury, Ormond has arranged for Gallicoís subsequent 44th Steet booking to be cancelled, and the date handed over to Rinaldi, who will naturally be performing Gallicoís decapitation trick as part of his act. To add yet further insult to injury, Ormond turns out also to have stolen Gallicoís wife, Claire (Eva Gabor), some years ago by playing to the womanís voracious appetite for other peopleís money. Not long after putting Gallico in his place, Ormond takes advantage of a quiet moment in Gallicoís studio to gloat about both of his victories over the younger man. A word of advice: if you should happen to encounter a man who is being played by Vincent Price, donít piss him off!!!! Ormond makes that mistake here, and sure enough, itís the last time he ever screws up anything in his life. (Notice the complete lack of spraying blood when Gallico turns the decapitation machine on its owner.)

But now Gallico has a problem-- what to do with whatís left of Ormond? Luckily, Karen comes to his rescue. She stops by the studio and tells him that the local university is having a big bonfire party to celebrate its victory over a rival schoolís football team. Remember, Gallico is a master of disguise. He had already been working on a mask that would render him indistinguishable from Ormond, and at Karenís mention of the bonfire, he decides to dress up as Ormond and go to the university to throw the real Ormond on the pyre, the body disguised as an effigy of a player from the defeated team. Afterwards, he means to arrange for the rental of an apartment on the other side of town, still wearing his disguise, so as to give the impression that Ormond has gone into hiding for some reason. Itís a good plan, but it almost falls apart before it can get off the ground because, when she leaves Gallicoís studio, Karen confuses her handbag with the one in which Gallico had concealed Ormondís severed head. Gallico manages to get his bag back, but not before it had found its way into the hands of a cop, who (fortunately for Gallico) never bothered to look inside.

The other major flaw in Gallicoís plan, and the one which ultimately proves his undoing, is the fact that the woman (The Batís Lenita Lane) from whom he rented a room as Ormond happens to be a writer of mysteries. Thus, when the curious happenings begin to pile up, they do so under the scrutiny of someone capable of putting all the pieces together. For instance, it doesnít take long for Claire to notice that her husband has vanished. She concludes that he is hiding from her, and that Gallico is helping him do it. When Claire puts an ad in the paper, it is spotted by Mrs. Prentiss (the novelist), who recognizes the photo of Ormond as her new boarder, and who promptly gets in touch with Claire. Because Gallico had, for the sake of appearances, been in the habit of turning up from time to time at the Prentiss house in the guise of Ormond, itís only a matter of time before he does so and finds Claire waiting for him. Claire, of course, is the only person who can see through Gallicoís ruse-- after all, she has lived with both Gallico and Ormond-- and Gallico is forced to kill her to keep his secret from being revealed.

Itís all downhill from here for Gallico. Not only is Mrs. Prentiss now in full Agatha Christie mode, but Rinaldi, too, catches on to Gallicoís scheme, forcing him to commit yet another murder, while Lt. Bruce closes in on Gallico as well, using the new and experimental technique of fingerprint identification. (Did I mention that The Mad Magician is set in the late 19th century?) Iím sure you can see where this is going, and if I tell you that Gallico had earlier developed a spectacular new illusion employing a crematorium capable of producing 3500-degree heat, Iím sure you can also predict how Gallico is going to get whatís coming to him.

Thereís something very interesting going on in this movie that I want to draw your attention to, particularly because it is merely a more extreme manifestation of a phenomenon I have often observed in horror movies from the 1950ís. If you really look closely at Gallicoís character, you will see that he is not, at his core, an evil man. Granted, he murders three people and attempts to murder a fourth, but all of his victims are completely amoral scumbags who have wronged him in the past, and who threaten to wrong him even more egregiously in the present and future. The only innocent on whom Gallico turns his sights is Bruce, the policeman who finally corners him and threatens him with the disciplinary power of the state. It is thus hard to see Gallico as the villain of the film, and this identification is not made any easier by the fact that, of all the characters, Gallico gets by far the most screen time. As I said, this is by no means the first time that I have encountered this particular form of moral ambivalence in a 50ís horror movie, though Iím not sure Iíve ever seen it presented so baldly before. In fact, I would almost be willing to say that I canít recall a single truly evil 50ís Hollywood villain that didnít climb out of a flying saucer. Aliens and atomic monsters seem to be just about the only ones that seriously and willfully harm the innocent in these films. The human villains, for the most part, are (like Gallico) motivated to do evil out of an entirely understandable desire for revenge upon characters who are far more corrupt than they are, or (like most of the mad scientists) have admirable intentions that are derailed into evil by naivety or hubris. And, interestingly enough, on those rare occasions when we are presented with a genuinely despicable villain (Dr. Brandon from I Was a Teenage Werewolf springs to mind), the story is usually constructed in such a way that they do evil by causing an otherwise innocent character to harm others, rather than by doing the deeds themselves. I find it fascinating that this phenomenon should crop up in movies made during a decade now regarded as a time of simplistic, black-and-white notions of morality. The great irony of the situation is that Iím almost sure that the explanation for it has something to do with the eraís high-profile crusades against ďimmoralityĒ in entertainment. My theory is that the moralists of the day found the depiction of random violence against the innocent so objectionable, and were so successful in making their objections heard, that the entertainment industries (the movies, for our purposes) were forced to respond by making sure that those who suffered at the hands of their villains could not be perceived as innocent. The main, probably unforeseen, consequence of this practice was to make the nominal villains of the movies seem sympathetic in comparison to their victims, who, after all, clearly deserved what they were getting. What Iím suggesting here is that the efforts of those concerned citizens who sought to reign in what they saw as the immorality of the horror movie, by their very success, led to a decadeís worth of movies that depicted a moral universe which the moralizers ultimately responsible for their creation would have found even more disturbing had they actually given the subject any thought. Like the saying goes, be careful what you wish for...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact