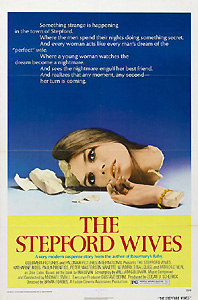

The Stepford Wives (1975) ***

The Stepford Wives (1975) ***

One thing that has amused and baffled me for many years is the almost superstitious terror with which many suburbanites regard the big city. I’ve marveled over it ever since I was a teenager trying to convince my girlfriend’s mom that I wasn’t going to get her daughter killed by taking her to see my band play at the World Headquarters in Curtis Bay— a fairly crappy neighborhood in the early 90’s, to be sure, but hardly Ice Cube’s Compton or Frank Henenlotter’s 42nd Street. Equally baffling and amusing, however, is the almost superstitious terror with which many urbanites regard the suburbs, a form of paranoia that I find far more interesting, simply because it is so often allowed to go unengaged. Media scholars can make and have made entire careers examining all the ways popular culture teaches us to fear the Concrete Jungle, but much more rarely does one see the same sort of critical attention paid to how we’re encouraged to believe that the first time you mow the lawn, your soul dies. In fact, I don’t believe I personally have ever seen such a thing. Perhaps it’s because media scholars themselves tend to be city people by temperament, regardless of where circumstance has actually sent them to live. Let me then take a small step toward redressing that cultural oversight, for The Stepford Wives is more than an allegory of backlash against women’s liberation. Underneath that thinly disguised subtext is a sub-subtext warning that the suburbs suck the humanity out of anyone foolish enough to venture there, replacing even the most vital and progressive individuality with reactionary selfishness and empty-headed conformity.

Like a lot of well-to-do white Manhattanites in the 1970’s, attorney Walter Eberhart (The Exorcist’s Peter Masterson) and his wife, Joanna (Katharine Ross, from The Swarm and The Legacy)— the latter an aspiring photographer— have decided that the time has come to make their escape from the big city. The Eberharts have two young children, and as they see it, New York is increasingly becoming no place to raise a kid. With that in mind, the family is relocating to the charming suburb of Stepford, Connecticut, close enough for Walter to commute to his office uptown more or less painlessly, but comfortably far away from the rising tide of urban blight. It sounds like a reasonable plan, but one major flaw in it is evident from the outset. Despite the fiction she tries to maintain that moving to Stepford was as much her idea as Walter’s, Joanna really has no desire whatsoever to leave the city. So far as she’s concerned, the Connecticut suburbs might as well be the far side of the moon, and she not-so-secretly resents her husband for banishing her there.

There undeniably is a strong element of culture shock to the move. Stepford is the kind of place where new arrivals are instantly set upon by the daffy old lady (Paula Trueman) who writes the gossip column in the cheesy local paper, interrogating them about their jobs, interests, hobbies, and histories. It’s also the kind of place where your across-the-street neighbors send the lady of the house over to welcome you with a freshly made casserole. Said lady of the house is Carol Van Sant (Nanette Newman, from House of Mystery and Captain Nemo and the Underwater City), and while Walter greets her with what looks like a mix of discomfiture at the old-fashioned-ness of the gesture and nostalgia for a bygone era’s notions of domesticity, Joanna’s reaction is much purer. She’s not one tiny bit impressed with Carol or her husband, Ted (Josef Sommer, of Iceman and The Henderson Monster). It takes her very little time to suss out that Ted is a domineering prick, but Carol presents herself with such bovine docility that it’s difficult to drum up much sympathy for her. Either she spends her whole life pilled up, or there’s something seriously wrong with the woman. I mean, raising no objection when her husband feels her up in the front yard might fall under the heading of Different Strokes, but who the fuck apologizes to the paramedics for putting them to so much trouble while they load her into the ambulance after a head-cracking car accident?

There’s one thing about Stepford that Joanna hates more than any other, the avowedly-all male status of the only apparent social organization in town, and when Walter accepts an invitation to join it, it touches off what might just be the most serious fight in the history of the Eberharts’ couplehood thus far. Joanna does see the logic behind Walter’s decision to join the Stepford Men’s Association (professionally speaking, it behooves him to be well connected to the local well-connected, and there’s supposedly an internal movement afoot to open the association to women anyway), but she still takes it as an affront to everything she believes in— and to everything she thought her husband believed in, too. Her distaste for the Men’s Association (and by extension, for Stepford) increases still further when Walter invites the key members over to the house one evening, permitting her to meet a few of Hubby’s new cronies. Apart from Ike Mazzard (Macabre’s William Prince), a formerly famous men’s-magazine pinup artist whom Joanna apparently dislikes on principle (but dislikes slightly less after he presents her with a portrait he sketched of her during the association leaders’ visit, in which she looks fully worthy of her own wartime Esquire pictorial), the whole lot of them are unendurable bores— and association president Dale “Diz” Coba (Patrick O’Neal, from The Mad Magician and Silent Night, Bloody Night) is an unendurable boor as well. Rude as it is, one can’t entirely blame Joanna when she insults Coba to his face as soon as circumstance places them alone together. (“Why do they call you ‘Diz’?” “I used to work for Disney World.” “No, really.” “That is really.” “I don’t believe you.” “Why not?” “Because you don’t look like someone who enjoys making people happy.”)

In fact, it seems the only person or thing in Stepford that Joanna does like is Bobbie Marcowe (Saturday the 14th’s Paula Prentiss), the rather irascible fellow newcomer who looks her up after reading the little puff piece on the Eberharts in the Stepford Chronicle. Extrapolating from Joanna’s answers to the stock new-in-town questions, Bobbie rightly figures that she’s finally found someone else “who, given complete freedom of choice, doesn’t want to squeeze the goddamn Charmin.” Joanna and Bobbie very quickly agree that their big project will be to drag the other women of Stepford into the 1970’s, whether they want to make the trip or not. In particular, they want to set up a feminist counterpart to the Men’s Association, so as to engage in a bit of that most quintessentially 70’s sociopolitical activity, consciousness raising. They don’t meet with very much success. Between the two of them, Joanna and Bobbie talk to just about every adult female in town, but the only nibble of interest they encounter comes from Charmaine Wimpiris (Tina Louise, from Evils of the Night and Look What’s Happened to Rosemary’s Baby), a tennis-loving wannabe femme fatale who might just be pricklier than the two self-appointed activists combined. The rest of the Stepford wives might as well be so many clones of Carol Van Sant. Not only do they uniformly assert no interest in women’s liberation, but they all plead impossibly busy schedules of cooking, cleaning, and looking after the kids. What’s more, those whom Bobbie and Joanna ask directly aver that their lives of seemingly obsessive homemaking offer all the personal fulfillment that they require, and when the two agitators finally do succeed in finagling a meeting of the Stepford women, it quickly devolves into a forum for comparing notes on the virtues of various cleaning preparations. I believe we can safely say that that was not the sort of consciousness-raising Joanna and Bobbie had in mind!

Now that’s all very frustrating for our heroines, but we’ve also been seeing hints for some time that Stepford holds dangers far worse than boredom and social dissatisfaction. For example, shortly after Carol Van Sant’s car crash, Joanna sees her acting incredibly strange at some sort of community event organized by the Men’s Association. Carol explains later that she was making a drunken fool of herself (confessing, while she’s at it, to a history of alcoholism), but she didn’t look like any drunk I’ve ever seen. What she looked like was a piece of malfunctioning animatronics, cycling through a repetitive set of motions over and over again and repeating the same inane sentence, with exactly the same cadence and inflection, at disturbingly regular intervals. Later on, an encounter with the Chronicle gossip columnist brings to light the head-scratching information that not only was Stepford once a hotbed of women’s lib activism, but that Carol of all people was the president of the now-extinct Women’s Association. Meanwhile, the Stepford police seem suspiciously vigilant in chasing non-members off the grounds of the historic mansion that now serves as the Men’s Association headquarters, and somebody has made off with the Eberharts’ small but very noisy dog. Then Joanna and Bobbie notice Charmaine’s husband (Franklin Cover) overseeing the demolition of her beloved backyard tennis court, and when they pop in to see what in the hell that’s about, they find that the only other fully autonomous woman in Stepford has somehow transformed into a domestic zombie like all the others. Bobbie freaks out good and proper at that, concocting a paranoid theory that some chemical runoff from the numerous tech-sector manufacturing plants outside of Stepford is leeching into the water supply, and doping the women who drink it into a stupor of placid obedience and compulsive housekeeping.

By a remarkable coincidence, Joanna is in a position to test her friend’s hypothesis, because an old ex-boyfriend of hers (Robert Fields, of Frankenstein Meets the Space Monster and The Blob) is now a professional chemist. He finds nothing out of the ordinary, however, when he performs a chemical analysis on the water sample that the women bring him. Really, though, clues to the mystery of the Stepford wives are all around Joanna, if she would just look closely enough in the right places. Places like those very detailed drawings of her that Ike Mazzard made when he was over at her house with the rest of the Men’s Association. Places like the weird favor Association member Claude Axhelm (George Coe, from The Entity) has Joanna doing for him, recording herself reciting a long list of relatively common words, ostensibly as part of a project to map regional accents scientifically. Places like the community party where Carol’s bump on the head manifested itself in a repeating loop of stock words and gestures. Places like Coba Industries, where the man with his name on the building is also the head of the Men’s Association, and used to devote his engineering talents to creating animatronics for Disney World before he got rich enough to found his own company.

On the allegorical/satirical level, The Stepford Wives doesn’t really work for me. The film’s sexual politics look quaintly dated, naturally, but there’s more too it than that. After all, creating the perfect woman artificially to circumvent the hassles that inevitably come with the real thing is a fantasy that never goes out of style. The trouble is that I can’t buy into the form that fantasy takes here. I mean, come on— the men of Stepford have it in their power to remodel their wives into any kind of women they please, and without exception, they opt for dowdy, matronly, dim-witted things that do nothing but bake, dust, and garden all day? Even accepting that the whole town is mentally stuck in the 50’s, you’re telling me that not one of these guys would rather have his own personal Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, or Bettie Page? Sorry, but that’s ridiculous. If the aim is to critique what men want in a woman, it’s important for the fantasy to be plausibly attractive— that it actually represent something that you can imagine a man wanting. But as the behavior of the Stepford husbands plainly shows, even they don’t really want this reductio ad absurdum of 1950’s motherhood. The Stepford men neglect and avoid their robot wives just as thoroughly as they presumably had the originals; it’s just that the mechanical versions are programmed to be content with neglect and avoidance. I could understand this bizarre interpretation of male relationship fantasies if The Stepford Wives had been written by a woman, but with William Goldman adapting the screenplay from a novel by Ira Levin, I must admit that I’m pretty completely flummoxed.

Or maybe not. Maybe it does make a certain amount of sense if instead of looking into their own ids to develop the Stepford programming, Levin and Goldman were attempting to extrapolate what those men would find desirable— those scary sons of bitches who reject the self-evident superiority of the city lifestyle and actually like dwelling in the world of cul-de-sacs and two-car garages. (Sarcastic? Who, me?) The Stepford wives may be risible as embodiments of male desire, but as a straw-man argument against the burbs, they do have a fair amount of crude rhetorical power: “Here— you see how horrible it is out there beyond the beltway? Not only do those people enjoy their boring lives, but spend a few months among them and they’ll make you want to live that way too!” The greatest strength of The Stepford Wives is that it does a really good job of making that straw-man argument. It’s still bullshit (I’ve lived in the suburbs all my life; if doing so turns you into a shallow conformist, chalk it up to your weakness of character, not to the insidious power of the environment), but it’s bullshit put forth with a terrible and momentarily persuasive eloquence. However little scrutiny the motives for the conspiracy against Joanna can withstand, there’s no gainsaying the commitment the filmmakers bring to bear in presenting its effects, and as a tale of paranoia that turns out to be all too well justified, The Stepford Wives falls only a little short of the standard set by Rosemary’s Baby seven years earlier. It helps a lot, given the thematic concerns of the film, that Katharine Ross’s Joanna is (with one inexplicable lapse at a key moment during the climax) such a legitimately strong and resourceful character. There’s no mistaking how much would be lost if she were replaced by another of Coba’s robots, and it is thus truly horrifying when Walter gradually accommodates himself to the idea of trading her in. The scene in which Joanna confronts her unfinished doppelganger is the movie’s real masterpiece, not least because of the unique way in which this specific gynoid is portrayed. Bustier, curvier, and all-around sexier than the real Joanna, the fake one is the only “improved” Stepford wife to offer any recognizable benefit to counterbalance what she lacks in intelligence, drive, and personality. Maybe that’s significant, too, because Walter, after all, is not naturally a Stepford man. He had to be seduced by this suburban dystopia, and it had to offer him something for which one could believe him selling out. If only this movie’s creators had understood that the same applied just as much to the other men, The Stepford Wives would be a much stronger satire than it is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact