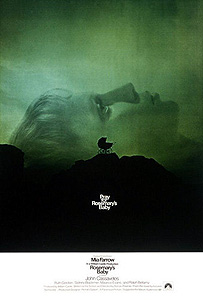

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) ***½

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) ***½

Of all the movies I know of which almost got made but didn’t, I think the one I would most like to have seen is William Castle’s Rosemary’s Baby. Castle, who was working for Paramount at the time, bought a three-year option on Ira Levin’s novel of big-city Satanism before it was even published. (He somehow got a look at the proof galleys, and decided the property was a sure-fire winner.) His bosses at the studio, however, thought the project had so much potential that they couldn’t afford to let Castle direct, lest he give them something along the lines of Strait-Jacket or The Night Walker. And they had a point, too— I willingly concede that. Roman Polanski turned in a much more sober and mature movie than Castle probably would have, and since Paramount’s leadership wanted to handle Rosemary’s Baby as a highbrow horror film for a mainstream audience, giving the job to somebody like Polanski was the only sensible thing to do. But at the same time, I like those weird, cheap, garish little movies that Castle was making in the mid-1960’s, and I would love to have seen how the man behind The Tingler would have handled a conspiracy to bring the Antichrist into the world through the womb of a lapsed Catholic. I’m sure we came out ahead with the version we got, but still…

TV and stage actor Guy Woodhouse (John Cassavetes, of The Incubus and The Fury) and his wife, Rosemary (Mia Farrow, from Secret Ceremony and The Haunting of Julia), are in the market for a new apartment. After looking around a few other places, they stop by a very old, very beautiful building called the Bramford, where there is a spacious, four-room suite available at the very top end of their price range. As the superintendent (Elisha Cook Jr., of Voodoo Island and Salem’s Lot) shows the Woodhouses around, he explains that the previous tenant has just recently died, and that if they’re interested, they could probably snap up most of the old lady’s furniture along with the apartment. The old-fashioned, oppressive furnishings aren’t to Rosemary’s taste, but she loves the space itself, and she leans hard on her husband to make a deal. Guy caves to the pressure (the Bramford is, after all, within easy walking distance of the theaters where most of his jobs are likely to be), and a week or two later, the Woodhouses are firmly ensconced within their new digs. Rosemary even makes a new friend, a young woman named Terry Gionoffrio (Victoria Vetri, from Invasion of the Bee Girls and When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth), who lives on the same floor as Rosemary with an old couple called the Castevets. In fact, their unit shares a common wall with Rosemary’s, and the two flats had originally been sections of a single huge apartment. Evidently Minnie (Ruth Gordon, from Whatever Happened to Aunt Alice?) and Roman (The Lady and the Monster’s Sidney Blackmer) Castevet never had children of their own, and it scratched their parental itch to take Terry in and straighten her out when they discovered her on the streets, whoring and doping and shoplifting her way to an early grave.

Guy and Rosemary’s friend and former landlord, Edward Hutchins (Maurice Evans, from Terror in the Wax Museum and Planet of the Apes), has a slightly different take on the Bramford, however. Over dinner with his vacating tenants, Hutch spins a long series of yarns detailing a history of ugly events that have happened in the old building. First, there were the Trench sisters, a pair of spinsters who lived at the Bramford when it was new, and who made a name for themselves by killing and eating several small children. Then there was Adrian Marcato, another illustrious Bramford tenant of the 19th century, and a self-proclaimed warlock and practicing Satanist. And of course, there was the usual succession of murders, suicides, and descents into insanity without which no haunted house— or haunted apartment complex, either, for that matter— would be complete. Hutch doesn’t take any of that colorful history terribly seriously, but he figures Guy and Rosemary might want to know about it if they’re going to be leasing a flat at the Bramford. A lot of folks wouldn’t want to live under a roof that had seen that kind of action.

In point of fact, the Bramford’s troubled past is about to carry over into a troubled present. Soon after moving in, Guy and Rosemary come home from a late night out on the town to discover that Terry has leaped to her death from the window of the Castevets’ apartment. Roman and Minnie were out at the time, too, and they, like the Woodhouses, return just as the police are cleaning up the mess and trying to make sense of the situation. Roman seems to take Terry’s death more or less in stride, but Minnie is devastated. In the days that follow, Rosemary finds herself spending a great deal of time with Minnie, who is obviously in need of some youthful company just now. The old lady strikes Rosemary as nosy, intrusive, and vaguely uncouth, but not without a certain grandmotherly charm for all that, and in any case, Rosemary herself is far too polite to tell Minnie that she’s invading her personal space by popping over at all hours of the day. Guy initially shares his wife’s feelings, but after he meets Roman when he grudgingly accompanies Rosemary to dinner at the Castevet place, he decides that his elderly neighbors aren’t so bad after all. Roman has led a busy life, traveling to just about every inhabited spot on Earth in his 79 years, and his mind is plenty sharp enough for him to pour out his accumulated stories in a cogent and entertaining manner, unhindered by the rambling and repetition that so often attend the reminiscences of the very old. Indeed, before long, Guy starts spending enough time with the Castevets to make Rosemary jealous!

Soon after Guy starts making a point of hanging out with Roman, the circumstances of his life take a major upturn, although in a somewhat macabre manner. He unexpectedly lands a role in an important play which he had been turned down for, the actor who was chosen instead having been suddenly and inexplicably stricken blind. About the same time, he spontaneously suggests to Rosemary that the two of them have a baby, something she had long desired, but which it is implied Guy had been resisting. He even goes so far as to work out which dates would be most auspicious for conception. On the first of these dates, Minnie comes over unannounced to give her neighbors some test samples of a new chocolate mousse recipe she’s trying out, but she uncharacteristically allows herself to be shooed away after handing over the experimental desserts, rather than sticking around and scuttling Guy and Rosemary’s romantic evening. Rosemary complains of a chalky taste in her mousse, and an hour or so after dinner, she is struck by a wave of dizziness. It gets so bad that Guy has to carry her to bed, where she spends the night having strange and disconcerting dreams. In the worst of these, Rosemary is tied down to a bed in the Castevets’ living room, where a huge crowd of chanting old people look on while some kind of inhuman thing (it rather reminds me of the creature in The Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow, actually) has sex with her. When she awakens the next morning, her body is covered with shallow scratches, and Guy sheepishly admits that he had sex with her while she was passed out. “Didn’t want to miss Baby Night,” he justifies rather lamely.

Rosemary does indeed become pregnant, and in her excitement, she fails to notice at first the odd reactions the news elicits from Guy, Roman, and Minnie. Her friend Elise (Emmaline Henry) had steered her toward an obstetrician named Hill (Charles Grodin, from the Dino DeLaurentiis King Kong), but the Castevets insist that she go instead to a friend of theirs named Dr. Abraham Sapirstein (Ralph Bellamy, of The Wolf Man and The Ghost of Frankenstein), who is widely regarded to be one of the best (and, not coincidentally, most expensive) OB/GYNs in New York. Minnie even talks him into giving the Woodhouses a substantial discount. The course of prepartum care which Sapirstein prescribes is curious indeed (it involves lots of herbal potions prepared by Minnie Castevet), but Guy is adamant that Rosemary adhere to it, even when she begins losing an alarming amount of weight and experiencing steady, intense pain in her abdomen. In fact, Guy has pretty much turned into a yes-man for Minnie ever since word came back that Rosemary was pregnant. Eventually, Rosemary’s other friends begin to suspect that something may be wrong, and Hutch discovers that some of the rarer ingredients in Minnie’s herb drinks had historically been used in the practice of witchcraft. Before he can progress any further in this line of inquiry, however, Hutch lapses into a coma, where he remains until his death three months later. But just before the end, he regains his senses sufficiently to send an old friend, Grace Cardiff (Door-to-Door Maniac’s Hanna Landy), to Rosemary with a book he picked up and the message, “the name is an anagram.” The book is called All of Them Witches, and in it Hutch has highlighted several passages which have eerie parallels in Rosemary’s life since she moved into the Bramford. It also has a chapter on the notorious Adrian Marcato, which contains the information that Marcato had a son named Steven, who was born the same year as Roman Castevet. And after a few futile stabs at rearranging the letters in “all of them witches,” Rosemary realizes that “Roman Castevet” is an anagram for “Steven Marcato.” All at once, Rosemary thinks she understands what’s going on. Steven/Roman is a Satanist like his father, the circle of well-heeled old geezers who periodically convene at the Castevet apartment are a coven of witches, and Guy has thrown his lot in with them in order to advance his wobbly acting career. That dream she had on the night when her child was conceived was no dream, and as soon as the baby is born, the Marcato coven will take it to use for some unholy ceremonial purpose. And of perhaps the gravest import, Hutch’s death and the blindness which afflicted Guy’s professional rival were almost certainly the result of hexes cast by the Devil-worshipers. The only person Rosemary can think of who might be able to help her is Dr. Hill, but how the hell is she going to convince him that she isn’t just out of her mind with prepartum hysteria?

Rosemary’s Baby takes a noticeably different tone at each stage of the story, and some of those combinations of narrative voice and subject matter work better than others. The soap-opera-like first act begins to grate after the initial exposition is out of the way, and the second act is compromised by Polanski’s insistence upon treating the strange goings-on around Rosemary’s pregnancy like a mystery, when in fact it is immediately obvious that the devil-sex “dream” sequence is really happening, and that its loose and hallucinatory quality is due to the chalky-tasting drug which Minnie Castevet slipped into Rosemary’s chocolate mousse. We already know what’s going on, and Polanski risks eroding our sympathy for Rosemary to the breaking point by taking so long to have her catch up to us. However, once Rosemary gets it into her head that she has been the victim of some kind of Satanic plot, Rosemary’s Baby whips itself into shape and turns into one of the screen’s best-ever variations on the theme of “just because you’re paranoid, that doesn’t necessarily mean everybody isn’t out to get you.” The scene in which Rosemary explains herself to Dr. Hill is terrific; as she spills it all out from beginning to end, it gradually dawns on the audience how utterly demented the story sounds, until even we are no longer so sure of Rosemary’s sanity. It’s a commendable trick Polanski pulls off there, suddenly making us doubt what we have accepted without question for the full length of the film up ‘til then. Finally, when the baby’s birth ushers in the climax, the film takes another sharp tonal turn, veering into black comedy for the last few minutes. Out of nowhere, the Castevets’ hitherto menacing cult comes to seem absurd— a bunch of old fogies trying to bring about Armageddon when they can’t even get it together sufficiently to quiet a squalling baby. And unlike the last time Polanski tried to combine humor and horror, the final scene of Rosemary’s Baby really works.

More than anything else, I think it’s Mia Farrow’s performance that holds Rosemary’s Baby together. From the beginning until nearly the end, she seems totally out of her depth, but in a way that inspires compassion rather than dismissal. When you think about it, the whole story is predicated upon a woman of weak will, accustomed to trusting in others to keep life running smoothly and constantly second-guessing her own instincts. At the age of 23, Mia Farrow had a childish quality about her that suited this movie’s purposes perfectly, but combined with enough palpable intelligence to make it just as believable when Rosemary finally turns the corner and starts looking out for herself and her unborn child. When the turnaround comes, the reaction it inspires is akin to that which elementary school teachers must feel when a bright but struggling pupil makes the decisive mental connection that enables him to grasp a difficult math problem. Mounting frustration disintegrates, and you want to exclaim, “There! You see? I knew you could do it!” With a less engaging actress in the part, we might well give up on Rosemary during the long stretch between her date with the Devil and the cascade of eurekas that comes when she deciphers the puzzle of Roman Castevet’s name. But there’s something about Mia Farrow that makes you want her to be okay no matter how dense or hapless she might seem, and so the audience continues pulling for Rosemary even against its better judgement.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact