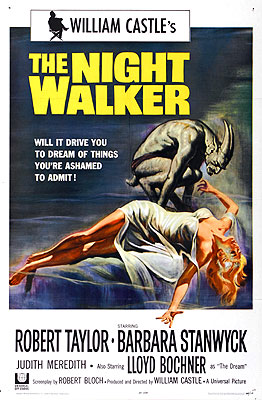

The Night Walker/The Dream Killer (1964) ***

The Night Walker/The Dream Killer (1964) ***

Itís always a pity to see someone give up on something for which they have a real gift. In director William Castleís case that gift was for carnie-style ballyhoo and showmanship. Who can forget the mad, desperate gimmicks Castle used to woo audiences to his movies between the mid-50ís and early 60ís? Percepto, Emergo, Illusiono, Homicidalís Fright Break, the poll to determine the villainís fate at the end of Mr. Sardonicus, the insurance policy against death by fright that Castle bought to cover the first-run audiences of Macabre. Ingenious scams all, and better still, scams that made the movies they served even more enjoyable. But as the 60ís wore on, Castle mostly turned away from such things, increasingly allowing his films to stand or fall according to their own intrinsic merits. Gimmicks or no gimmicks, however, Castle was still Castle, and his 60ís-vintage movies retain his distinctive directorial stamp. And as The Night Walker/The Dream Killer shows, that was ultimately good enough.

Many people call The Night Walker a Psycho ripoff, but while you could make a case for that, to say so is misleading. This movie really has very few echoes of Psycho, despite having been written by Psycho author Robert Bloch; rather, its model is Castleís own Homicidal, with its emphasis on insanely complex webs of backstabbing and intrigue. And although Homicidal unquestionably was a ripoff of Psycho, none of the elements Castle cribbed from Hitchcock were reused in The Night Walker. Thereís no psychosexual perversity on display here, just good old-fashioned avarice.

The Night Walker begins by introducing us to Howard Trent (Hayden Rorke, from When Worlds Collide and Project Moonbase), a blind scientist of undisclosed specialty who has become convinced that his wife, Irene (Barbara Stanwyck, in her last theatrical featureó it was strictly TV from this point on [The House that Would Not Die, for example]), is having an affair. Trent first came to this conclusion when he began to overhear Irene talking in her sleep. Every night (or as close to every night as makes no difference), Ireneís nocturnal mutterings reveal that she is dreaming of romance with a man other than her husband. And because the dreams seem to involve the same man every time (Irene drops enough hints about her dream loverís appearance for her husband to form a pretty good mental picture of him), Trentís belief that thereís more going on than mere subconscious longing is understandable. The question is, who could Irene be seeing on the side? She rarely goes out, and no one ever comes to the house.

No, waitó strike that. There is one man, after all. Trentís lawyer, Barry Moreland (Robert Taylor, Barbara Stanwyckís real-life ex-husband), comes around quite a lot, as a matter of fact, and come to think of it, he does fit the sketchy description Trent has pieced together of Ireneís dream lover (though sightless Trent naturally doesnít know that for certain). Moreland denies any dalliance with Irene when confronted by Trent, of course, and while the familiarity with which he treats Mrs. Trent does seem just the slightest bit suspicious at first, the conversation the lawyer has with the scientistís wife immediately after his talk with Trent establishes beyond a doubt that if Irene is having an affair, itís with somebody else.

But all of this is really just background, because on the very night that Trent brings his suspicions out into the open, he is killed in an explosion in his attic laboratory. So violent is the explosion, in fact, that not a trace of Howard Trent is left for the police investigators to find. Irene never gets much of a chance to enjoy her new-found freedom, however, because she immediately begins having extremely vivid nightmares in which Howard returns from the dead to take revenge on her. At first, she thinks the dreams will stop if she moves out of the house she and her husband shared, that if she puts some distance between her and the charred and twisted wreckage of Howardís ruined lab, her subconscious imagination will have less raw material from which to construct nightmares. But even after she moves back into the apartment she used to occupy in the back of the beauty parlor she owns, the dreams keep coming.

The move does seem to have had some effect on her, though, because in addition to dreaming of Howardís vengeful revenant, she begins to dream about her imaginary lover (Lloyd Bochner, from The Dunwich Horror and Satanís School for Girls) again. You might think this an improvement over her former situation, and maybe it is, initially. But one night, Irene has a very vivid dream in which her lover comes for her, takes her to his apartment for champagne, and then to a small chapel where the two of them are married in a ceremony in which all the other participants are decidedly creepy-looking wax dummies. Her lover vanishes immediately after slipping the ring onto Ireneís finger, and then the ceremony begins anew, with Howard as the groom! And when Irene awakens the next day, she canít shake the feeling that it was no dream she had the night before.

Barry Moreland is skeptical when Irene comes to him with her story, of course. You would be too. But eventually, he agrees to take her around town looking for the locations that figured in the dream. The apartment building is real alrightó in fact, it turns out to have belonged to Howard!ó but the dream loverís specific unit is empty when Barry and Irene go to check it out. The chapel is empty too, abandoned years ago by its congregation, but like the apartment, it is nevertheless very real. More to the point, so is the wedding ring Irene finds on its floor, a ring exactly like the one which her lover gave her in the dream. And even more to the point, so is the man of Ireneís dreams, who comes out of hiding in one of the chapelís side rooms just after Irene and Barry leave. Obviously, somebody is fucking with Mrs. Trent.

Could it be Howard? After all, nobody ever found any trace of his body after the explosion, and if he were still alive, it would be just like him to try to torment his wife into insanity in revenge for her ďinfidelityĒó hell, Howard would probably think Irene caused the explosion in the first place, to free her to pursue her mysterious boyfriend! Or maybe Fuller, the private investigator Howard hired to spy on Barry and Irene, is behind it all. Itís hard to imagine what the P.I. would stand to gain from such a thing, but he undeniably is a dead ringer for the dream lover, and his direct involvement in a conspiracy against Irene would at least explain how a man from her dreams could turn up in the real world. She would have been seeing Fuller out of the corner of her eye on a daily basis for months, giving her subconscious mind a face to attach to her unreal paramour. And while weíre at it, we ought not to rule out Barry as a suspect either. Heís been getting awfully close to Irene as a result of her little problem, and itís just possible that heís trying to maneuver himself into her heart while simultaneously messing up her mind enough to give him unobstructed access to Trentís fortune. Letís face it, who could know better how much money the old bastard was sitting on than the lawyer handling the probate on his estate? No matter what, you can be sure of two things. First of all, Joyce, the new girl at Ireneís beauty parlor (Judi Meredith, from Queen of Blood and Dark Intruder), is an accomplice in the plot. And second, Iím sure as hell not going to tell you what the real story isó Iíve got way too much respect for this movie for that.

Like I said in the beginning, itís something of a disappointment to see a William Castle movie with no tacky gimmick, but the fact of the matter is that by the time he got around to making The Night Walker, Castle had honed his talents as a director to the point that he no longer needed that kind of a crutch. True, the ending of this movie teeters precariously on the edge of the ďScooby DooĒ abyss, with the true nature of the plot against Irene revealed in a manner best suited to the mentality of the disproportionately young Saturday matinee audience, but given the fact that this audience had always been Castleís bread and butter, this shortcoming is both understandable and forgivable. And true again, the conspiracy proves to be so incredibly complicated as to put a real strain on audience credulity, but villainous schemes of Byzantine complexity had been a staple of Castleís work since at least The House on Haunted Hill, and Iíve always found them to be much of the fun in these films. Itís probably no coincidence, in fact, that the movie in which Castle kept the shortest leash on this tendency of his, Mr. Sardonicus, is the one that I found the least satisfying to watch. With those two potential complaints disqualified, the only significant problem remaining with The Night Walker concerns Ireneís reaction to the ďdreamĒ in which she is married to the mystery man. There is nothing in the way this sequence is handled that suggests it to be anything but a dream until Irene discovers the ring in the chapel the next day, and thus it is more than a little baffling when she awakens in the morning convinced that the surreal chain of events we witnessed actually did occur. Because this is such a pivotal moment in the story, its mishandling does real damage, and it is a strong testimony to Castleís capability as a director that he was able to regain his footing and bring the movie back under control. The Night Walker is far from being Castleís finest achievement, but it is nevertheless a much better movie than it is generally given credit for being.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact