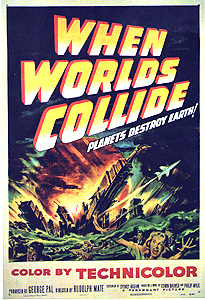

When Worlds Collide (1951) **

When Worlds Collide (1951) **

If you were paying attention a few years ago, it would have been hard for you to avoid noticing that the late 90ís were marked by the latest outbreak of the movie industryís sporadically recurring mania for gigantic objects from space plowing apocalyptically into the Earth. In the theaters, we had Armageddon and Deep Impact, while television weighed in with what seemed like hundreds of films on the order of Asteroid and Doomsday Rock, including (if memory serves me) one or two which bore what many avid B-movie fans rightly consider to be among the most frightening slogans in the English language: ďA Sci-Fi Channel Original.Ē But as I said, those movies were only the latest in a long, long lineage. As with so many of the dominant themes of modern science fiction, the World-Destroying Space Rock made its Hollywood debut in the 1950ís; in fact, its US earliest incarnation, When Worlds Collide, was part of the opening salvo of that decadeís famous science fiction explosion. And though it isnít a particularly good film, When Worlds Collide made a big impression, as it would almost have had to in an era during which the total destruction of the world as we know it was an idea forever lurking at the back of peopleís minds.

At an isolated observatory on a mountaintop in South Africa, astronomer Emery Bronson (Hayden Rorke, from Project Moon Base and The Night Walker) has gathered together the ominous data heís been collecting over the past several months, with the aim of shipping it off to America for examination by his most trusted colleague, Dr. Cole Hendron (Larry Keating). He has summoned a pilot named David Randall (Terror Is a Manís Richard Derr) to act as his courier, primarily because Randall has a reputation for total reliability, and for not caring much about what precisely heís being asked to deliver. Bronsonís data, you see, is potentially the most explosive body of information currently possessed by anyone in the world, and the scientist is greatly concerned about what could happen if it got out to the public before cooler heads had a chance to look over it and determine how to proceed. Bronson has chosen his courier well, for on the trans-Atlantic sea voyage Randall begins after flying the package to Great Britain, the pilot receives a steady stream of telegrams from just about every top-shelf newspaper in existence offering vastly more money than the scientist is paying him in return for a peek inside the box; Randall ignores every one of them.

In New York, Randall meets up with Dr. Hendronís daughter, Joyce (Barbara Rush, of It Came from Outer Space and Moon of the Wolf), who brings him to her fatherís lab. Evidently Joyce doesnít realize how little David knows, because on the car ride from the Port Authority, she lets out that if Bronsonís findings mean what he thinks they mean, then the world is going to be destroyed in less than a year. As Randall learns while hanging around the Hendron lab, Bronson has discovered a new star which he has named Bellus, which is orbited by an Earth-sized planet he calls Zyra. And more to the point, Bellus and Zyra are now hurtling through space on a direct collision course with Earth!

Bronsonís analysis checks out, and Hendron and his colleagues spring into action trying to convince the leaders of the world of the looming danger. Hendronís thinking is that, though our planet will certainly be destroyed, there may yet be a chance for a small segment of humanity to survive. Zyra will arrive in Earthís neighborhood first, not hitting but passing close enough to us to trigger a cascade of natural disasters greater than anything the planet has experienced since at least the end of the Cretaceous period. The upside of that is that Earthís gravity will pull Zyra out of its orbit around the runaway star, and when Bellus comes along nineteen days later and hits the Earth head-on, the unfathomable energy released should be enough to sever any remaining tie between it and Zyra. Zyra will thus be perfectly placed to serve as a replacement home for humanity. Admittedly, it will require an unprecedented feat of engineering to build a fleet of spaceships capable of interplanetary flight in the eight months remaining before the calamity is upon us, and it is far from clear whether or not Zyra is capable of supporting life in the first place, but given a choice between probable death and certain death, it seems perfectly rational to take oneís chances with the former. The trouble is, the leaders of the world (or at least their ambassadors to the United Nations) donít take Hendron at all seriously. They prefer to listen to Dr. Ottringer (Sandro Giglio, from War of the Worlds), another astronomer who contends that Bronson and Hendron are completely full of shit. In the words of the newspaper headlines that pop up the next day, Hendron and his colleagues are laughed out of the U.N.

Luckily for the species, governments werenít the only organizations that seemed capable of marshaling the necessary resources for a viable space program in 1951, and Hendron has rather more success in the private sector. He secures the cooperation of several multimillionaires, most notably the reprehensible Sydney Stanton (John Hoyt, from The Lost Continent and Curse of the Undead), and work immediately begins on the construction of a 490-foot rocketship designed to carry about 50 human beings, along with commensurate amounts of livestock, food plants, and non-living cargo. Rumor has it there are other such private projects in the works elsewhere in the world, but the movie doesnít much concern itself with any of them. Rather, its focus is on the building of Hendronís rocket, and on the process by which he and his fellow scientists gather together the talent necessary to make it fly by the time Bellus arrives to declare Game Over. As a sideshow, weíll also have a rather tiresome love-triangle plot involving David Randall, Joyce Hendron, and Joyceís fiance, Dr. Tony Drake (Peter Hansen), along with Sydney Stantonís continuing efforts to recast Hendronís mission as his own private life insurance policy. Thereís one point on which Stantonís assessment of the situation is much closer to the mark than the scientistsí, though. The closer Bellus looms in the night sky, the greater the chances that those not selected to survive the worldís death throes will rise up and try to take a seat on the space ark by force.

When Worlds Collide was based on a 1932 novel by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer. The book, perhaps unsurprisingly, is much more rigorous, scientifically speaking, than the later movie version, and presents an altogether more coherent vision of how the two rogue planets (and they are indeed both planets in Wylie and Balmerís telling) are going to destroy the world. What is a little bit surprising is how much more conservativeó and thus less interestingó the movie is than the novel from which it derives. Whereas screenwriter Sydney Boehm seems to envision the space travelers rebuilding society more or less as it stood once they make landfall on Zyra, the novel depicts the scientists running the show as being much more hard-headed about the tribulations the butt-end of humanity is going to face on its new homeworld. As an example, consider the very different handling the Randall-Hendron-Drake love triangle receives in the print version as compared to the celluloid. The movie casts it in exactly the same terms as every other love triangle weíve ever seen. Joyce and Tony plan on getting married, but then along comes this international man of adventure, who is far more enticing than Joyceís current love, instantly undermining the coupleís visions of their future together. The men, for their part, follow the expected evolution from strangers to rivals to friends-in-spite-of-themselves. In the book, however, the problem isnít Miss Hendronís vacillation between her two suitors but her and her fatherís belief that life on Bronson Beta (as Wylie and Balmer called the smaller planet) will necessarily be far different from life on Earth. With the total human population reduced to just a few hundred individuals (the novel also contemplates two vastly larger space arks), Homo sapiens may no longer be able to afford the luxury of monogamous pair-bonding in accordance with Western notions of romantic love. With that in mind, the novelís Joyce refuses to become attached to either man, hoping to lessen the emotional blow in the event that society should rebuild itself along totally different lines. A similar flinching from the stark pragmatism of the novel can be seen in the way the crew of the rocketship is chosen. The movie makes it a lottery, with everyone given an even chance of making it aboard, while the novel had Hendron and his colleagues hand-pick the crew on the triple bases of health, fertility, and useful skills or knowledge.

Probably the most unexpected thing about When Worlds Collide, however, is its generally lackluster quality as a simple spectacle. After all, weíre talking about a movie that posits the ultimate apocalypse, the complete physical destruction of the world. Considering the breathtaking vision of the worldís end that producer George Pal would serve up just two years later in War of the Worlds, youíd think this movie would have a little more oomph to it. The space ark and its construction site never look like anything more than the dinky toys that they were; most of the earthquakes, floods, and volcanic eruptions that attend the Earthís brush with Zyra have a remarkably chintzy feel to them; and when the ship finally reaches its destination, the otherworldly landscape of Zyra is depicted by what might just be the single worst matte painting Iíve ever seen. The only point at which When Worlds Collide really works the way itís supposed to is during the drowning of New York City, which seems very real indeed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact