Terror Is a Man / Blood Creature / Creature from Blood Island (1959/1964) ***

Terror Is a Man / Blood Creature / Creature from Blood Island (1959/1964) ***

My last visit to the shadowy world of Filipino horror happened almost by accident. This time, however, Iím thinking of making a relatively leisurely examination of the subject in a more or less systematic manner, and consequently, Iím going to begin at the beginning. The Filipino movie industry was both small and primarily inward-looking at first, but that started to change around 1955, when producer/director Eddie Romero met and befriended an American former sailor by the name of Kane W. Lynn, who was then working as a technical consultant for the CBS television series ďNavy Log.Ē The TV gig had inspired Lynn with an interest in movie-making, and it quickly became apparent that he and Romero had something useful to offer each other. Romero, having been in the film business since at least 1947, had the hands-on experience and a solid network of reliable local talent. Lynn, meanwhile, knew people in Hollywood, raising the possibility of Romero penetrating the much more lucrative American market if he and Lynn were to team up. The resulting Lynn-Romero Productions was a short-lived enterprise, surviving only long enough to complete three feature films, but it laid the foundation on which the much more persistent and significant Hemisphere Pictures would later stand.

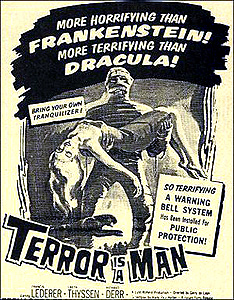

Hemisphere is a mostly story for another time, though. What concerns us right now is the odd picture out among those first three Lynn-Romero films, which can be seen as the clearest early signpost pointing in the direction of Hemisphereís future success. Whereas Lost Battalion and City of Sin were both war movies, Terror Is a Man is a horror film which prefigures the signature Hemisphere style of putting a deeply eccentric spin on tired and shopworn premises. It was quite successful in the Philippines, but initially failed miserably enough at the American box office to pass almost immediately into TV syndication. Perhaps it was simply a question of timingó certainly Terror Is a Man fared much better in 1964, when the newly-formed Hemisphere reissued it under the somewhat boring title Blood Creature. In fact, the reissue made so much money that Romero spent the rest of the decade spinning it off into a loosely organized series of increasingly sex-crazed and blood-soaked horror flicks set on Terror Is a Manís imaginary Blood Island. Thereís a big difference, however, between Terror Is a Man and what was to follow. Whereas the later Blood Island films unapologetically subscribed to the same schlock ethos that informed the output of Hemisphereís then-partners Independent International Pictures (the outfit that brought Al Adamson to the attention of a stunned and horrified world), this movie is an altogether more sober and thoughtful affair, essentially a loose adaptation of H. G. Wellsís The Island of Dr. Moreau.

After a quick peek at a map drawn in the style of the Age of Exploration establishes the setting as a remote locale in the South Pacific called La Ysla de Sangreó Blood Islandó we begin with a drifting lifeboat running aground on said islandís beach. The boat contains but a single passenger, an American named William Fitzgerald (Richard Derr, from When Worlds Collide), who is about to discover that heís the sole survivor of a shipwreck about 1000 miles from nowhere. Fitzgerald is found unconscious by a surgeon/medical researcher of French extraction, named Charles Gerard (The Return of Draculaís Francis Lederer), and his assistant, Walter Perrera (Oscar Keesee Jr., who would return to Blood Island in Brides of Blood), and is brought back to Dr. Gerardís villa for treatment. Upon awakening that night, Fitzgerald soon finds reason to suspect that he picked the wrong night to wash up on that particular beachó and not just because there wonít be any ships coming along to give him a ride home for at least three months, either. Conversation among Gerard, Perrera, and Gerardís wife, Frances (Greta Thyssen, of Journey to the Seventh Planet), keeps returning to the same subjectó that of a dangerous animal that has apparently escaped from the doctorís basement laboratory. The two men appear confident that they can catch it and return it to its cage, but Frances doesnít seem quite convinced.

Meanwhile, at the small village wherein live the only other inhabitants of Blood Island, that animal Fitzgeraldís hosts have been obsessing over is putting in an appearance. Sneaking up on a couple who are seated beside the fire in front of their hut, the beast kills first the woman and then the man. But the simple fact of the pairís death is far from being the most troubling thing about the whole situation. We never get a good look at their attacker, but what inconclusive glimpses we catch hardly make it look like any animal nature ever made.

The islanders seem to agree with that assessment, too. The next morning, every single last one of themó apart from a teenage girl named Selene (Lilio Duran) and her brother, Tiago (Peyton Keesee)ó boards the fleet of small fishing boats from which they apparently make their living, and sets sail for some other island. As for Selene and Tiago, the reason they chose to stick around is because they both work for Dr. Gerard, and are thus a bit more level-headed when it comes to the subject of things escaping from his lab. Fitzgerald learns about all of this when he goes out for a walk, and encounters first the abandoned village and then his hosts, who have spent the entire morning building a series of pit and drugged-bait traps for their wayward beastie. Gerard explains that the animal in question is a black panther that he brought with him as an experimental subject when he left the United States three years ago under somewhat stressful circumstances (presumably related to the reception that greeted his research in mainstream scientific circles). Obviously a pain-addled panther isnít the sort of creature one wants to run into alone, but the doctor figures heíll have it back in his custody by sundown at the latest. And indeed he does, but the recapture of the beast somehow doesnít seem to take the edge off of Francesís fears.

Fitzgerald will spend much of the rest of the movie piecing together precisely why that should be. The first clue comes when he sneaks downstairs to spy on Gerard and his wife (sheís trained as a nurse) while they perform some kind of surgery on the panther. It may be wrapped up completely in bandages when Fitzgerald sees it, but itís still perfectly obvious that the creatureís build resembles a manís far more than it does a big catís. Later, Fitzgerald gets a look at Gerardís notebooks, which the doctor has filled with odd sketches of panthers, men, and other things that seem to be somehow intermediate between the two species. This time, Gerard catches his guest snooping, and somewhat surprisingly, the scientist is perfectly happy to explain the whole strange business to Fitzgerald. Itís just what it looks like; the surgeon really has spent the last several years endeavoring to use his skill with the scalpel (and with other, more arcane instruments, too) to transform his panther into something approximating a man. In fact, Gerard plans to spend the very next morning rebuilding the animalís larynx so as to enable it to speak, and Fitzgerald is welcome to sit in and watch the operation if he wants. Fitzgerald canít say he approves of what the doctor is doing, but heís way too curious about it all not to take his host up on the invitation.

Now by this point, we've got a pretty good idea how everything is going to turn out. Gerardís homemade monster is going to have to escape from its cell in the villaís dungeon-like basement, and when it does, you can bet it wonít go well for the panther-manís creator. We can also safely assume that Frances is going to be on the receiving end of at least some of the creatureís attention. And we might further postulate that Walter will meet with the end prescribed for all monster-movie lab assistants. What makes Terror Is a Man worth the time in spite of its unoriginal plot is its highly original characterizations, that of Dr. Gerard especially. Nowhere will you find a movie about twisted science in which the scientist is so reasonable, so open in his dealings with those who have stumbled upon his hidden laboratory. Even Charles Laughtonís Dr. Moreau in Island of Lost Souls took pains to keep his work secret from his uninvited guests, upon whom he also quickly developed nefarious designs. But Charles Gerard honestly doesnít see anything at all wrong about his project for making a man out of an animal, and the moment Fitzgerald expresses an interest in it, the surgeon accommodates him with what looks like a combination of relief and pleasure at the prospect of finally being able to show off the amazing things that he has accomplished. Furthermore, the audience never receives even the faintest hint that Dr. Gerard means his visitoró or anybody elseó any harm. Whatís even more striking is Gerardís relationship with the panther-man. Though his experiments upon it inevitably cause the creature immense suffering, Gerard exhibits recognizable sympathy and even a strange sort of fondness for the thing. I can easily imagine a real-world scientist coming to feel the same way about his or her lab animals: desensitized to their pain but still genuinely regretful that it is a side effect of the experiments performed upon them. And of the greatest importance, Francis Lederer nails pretty much every aspect of this subtle and multifaceted role.

On the technical side, Terror Is a Man is one of the most beautifully shot movies Iíve seen in quite some time. This is probably the filmís most remarkable feature, seeing as one hardly expects first-rate cinematography from a 40-plus-year-old horror flick made in the Philippines! Terror Is a Man is one of those movies that really benefits from having been shot in black and white; for one thing, day-for-night always looks better in monochrome, and thereís quite a lot of that here. But at least as important is how far all the deep, dark shadows go toward establishing the somber, oppressive mood that director Gerry DeLeon endeavors to create. A strong sense of mood is necessary, because with the panther-man spending so much of the running time as a background presence, it would have been an easy matter for the film to get awfully dull awfully fast. As it is, Terror Is a Man still drags noticeably in the middle. Lucky for us, thereís enough substance at either end to make it all worthwhile on the balance.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact