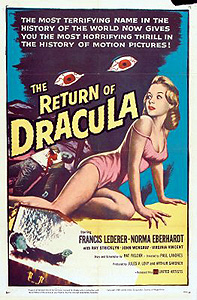

The Return of Dracula/The Curse of Dracula/The Fantastic Disappearing Man (1958) ***

The Return of Dracula/The Curse of Dracula/The Fantastic Disappearing Man (1958) ***

We all know what a big year for Dracula 1958 was. That was the year Christopher Lee first donned fangs and opera cape, giving rise to a series of films about the character nearly as iconic as Universal’s— nearly as long-lived and even more prolific, too. But there was another Dracula movie in 1958, an independent Hollywood production little seen and not nearly as highly regarded as Horror of Dracula, but in my estimation significantly more effective in realizing its limited and unusual aims. The Return of Dracula was part of the same little-noticed late-50’s horror cycle as Pharaoh’s Curse and The Werewolf, in which traditional gothic menaces like vampires, lycanthropes, and living mummies were brought into an immediately recognizable modern world, to be presented with few if any of the expected cobwebby trappings. And while it refrains from redefining vampirism on rationalistic, science-fiction terms in the manner of the same creative team’s The Vampire, The Return of Dracula arguably goes further than any of its contemporaries in updating the familiar premise. In The Return of Dracula, it is not the stagnation of the local peasantry that leads the undead count to abandon Transylvania for more promising hunting grounds, but rather the threat posed by the panoptic tyranny of Romania’s newly consolidated Stalinist regime.

That threat is established in the very first scene, when a government agent who will later be introduced to us (probably under an assumed name) as John Meierman (John Wengraf, of 12 to the Moon and Gog) leads a priest and a band of rough-looking men armed with crosses and stakes to the cemetery where he believes the infamous Count Dracula has established his latest hideout. Letting themselves into a large mausoleum just minutes before dawn, Meierman and his accomplices prepare to pry open the vampire’s coffin, and drive a stake through his heart in the first rays of the rising sun. But when the moment arrives, the coffin proves to be completely empty— nor is there any clue to Dracula’s whereabouts to be found in the crypt.

Meierman should have tried the train station. On what is either the next evening or perhaps even some hours before the cemetery raid, a young artist named Bellack Gordal (Frankenstein 1970’s Norbert Schiller) parts with his parents at some Transylvanian town’s railroad stop, and sets off on what was supposed to be the first leg of his journey out of the country, across the sea, and into the home of some cousins in America. Unfortunately, the man with whom Gordal is to share his compartment on the overnight train is none other than Count Dracula (Francis Lederer, from Terror Is a Man), and as soon as Bellack is settled in, the vampire strikes, helping himself to the traveler’s blood, baggage, and identity documents, and tossing the corpse down the railway embankment once everyone else on the train is safely asleep. Dracula continues along Gordal’s intended route, all the way to the small, Southern California hamlet of Carleton, where three and a half members of the Mayberry family are waiting to greet Cousin Bellack.

The matriarch of the clan is named Cora (Greta Granstedt). Presumably a war widow, she has been left alone to raise the now-teenaged Rachel (Norma Eberhardt) and her little brother, Mickey (Jimmy Baird), and she looks forward to having a man in the house again. Rachel likes the idea, too— or at least she likes the idea of having this specific man around. She’d apparently spent most of her childhood in correspondence with her old-country cousin, and Bellack’s tales of the hardships he’s had to endure as an artist living under a totalitarian regime have given her an idealized, almost Byronic image of him over the years. (Informed viewers, incidentally, will escalate their mental picture of those hardships considerably, based on the Hungarian-language sign on the platform at the train station back in Europe— so far as I know, no Romanian government yet has refrained from subjecting the Magyars of Transylvania to some manner of special mistreatment.) The auxiliary member of the Mayberry family who drives them all out to meet the train is Tim Hansen (Ray Strickland, from the 1960 version of The Lost World), Rachel’s boyfriend and the Mayberrys’ next-door neighbor. Tim is a lot sharper than he looks, and it takes him no time at all to discern that he is being compared to the false Gordal, and found distinctly wanting. Need I mention that Tim will spend a fair proportion of the movie being the only one who doesn’t trust this Bellack guy?

Speaking of distrust, it’s a good thing for Dracula that he’s picked an artist to bump off and impersonate. Without that longstanding cultural assumption that all artists are weirdos working for him, there’s no way he’d be able to get away with acting the way he does— sleeping all day, coming and going at all hours of the night, snubbing Reverend Whitfield (Gage Clark, of The Bad Seed and The Invisible Boy) when he comes over for dinner at the Mayberry house— without anybody other than Tim looking askance at him. And naturally the odd behavior that the Mayberrys and their neighbors see is the least of what Dracula gets up to. The reason “Bellack” always keeps his bedroom door locked during the day is that he isn’t really sleeping there at all, but rather in a coffin concealed in a disused mineshaft outside of town. The reason Mickey’s pet cat disappears, only to turn up dead a day or two later, is that Dracula was in the mood for a midnight snack. And most importantly, the reason Rachel’s friend, Jenny Blake (Virginia Vincent, later of The Hills Have Eyes and Invitation to Hell)— the blind girl who lives at the charity house run by Reverend Whitfield— suddenly starts wasting away is that the count has taken a liking to her, and has been visiting her while she sleeps. Jenny dies after only a few days of Dracula’s attentions, then rises again as The Return of Dracula’s Lucy Westenra figure. And if Jenny is Lucy Westenra, then that surely makes Rachel Mina Murray and Tim Jonathan Harker.

Fortunately, the ersatz Van Helsing is already on his way. Evidently it did eventually cross Meierman’s mind that Dracula might have hopped a train out of the country, and his search of the railway lines leading through the village where the count was last seen led him to discover the body of Bellack Gordal. Once the corpse was identified, it was a simple enough matter to guess the rest of Dracula’s itinerary, and now Meierman and an associate (Charles Tannen, from Gorilla at Large and The Monster that Challenged the World)— who almost certainly isn’t really named Mack Bryant— have come to Carleton, posing as agents of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. “Bryant” doesn’t last long; no sooner has he interviewed Cora Mayberry on the subject of her foreign cousin than Dracula sics Jenny on him. In an especially cool touch, she transforms into a wolf with fur the color of the dress she was buried in, and savages the vampire hunter to death at the train station where he had been searching for evidence to confirm that the man calling himself Bellack Gordal is really Count Dracula. That gets Sheriff Bicknell (John McNamara, of From Hell It Came and War of the Colossal Beast) involved, but cops don’t enjoy much of a track record against the undead in these movies. No, if Meierman is going to stop Dracula, he’d be better off courting the alliance of Reverend Whitfield— or, for that matter, of Tim Hansen.

The operative theory behind The Return of Dracula is essentially the same as that behind the much later Salem’s Lot— to transplant the basic plotline of Bram Stoker’s Dracula to small-town America and to update it to the present day. It doesn’t do it quite as well as Salem’s Lot, mind you, mostly because it depends far too heavily on the sustained inability of the Mayberry family to see what’s right in front of their noses. There’s no Marsten House in The Return of Dracula, nor any Richard Straker to conduct the vampire’s business for him during daylight hours and furnish him with cover stories as needed. Instead, Dracula just moves right in with the white-breadiest white-bread family you ever did see, and gambles on their naivety to keep him out of trouble. Since it’s hard to imagine anybody outside of a sitcom being that naďve, The Return of Dracula calls its credibility into question with its very premise, even without the undermining effect of the uneven acting, the cheap sets and completely unconvincing “European” locations, and a “wolf” that is all too obviously a big, friendly dog.

Fortunately, it has a few things working for it to make up for the credibility shortfall. Francis Lederer is an odd choice to play Dracula, but a pretty good one once you get used to him. His Czech accent is an asset, for one thing, and while he lacks the virility of Christopher Lee or the sheer peculiarity of Bela Lugosi, he has his own brand of gravitas that meshes well with the film’s deliberately prosaic setting. This is a Dracula who has been observing the modern world for long enough to fake a few of its ways, and while the palpable frustration that informs Lederer’s performance is probably really his dissatisfaction with the movie peeking through (near the end of his life, Lederer told an interviewer that The Return of Dracula was the only film he truly regretted making), it also strongly suggests the count’s distaste for a world that has lost all of its respect for hereditary nobility. Lederer takes full advantage, too, of those opportunities the script affords him to do something memorably unique with the character. Quite radically for a 1950’s film, The Return of Dracula implicitly paints the vampire as a sort of Antichrist figure; witness the almost liturgical monologue Dracula delivers when calling Jenny from her tomb for the first time, or his statement during one of his nightly visits to her room at the charity house that Jenny “will arise reborn in me.”

As the latter should make clear, The Return of Dracula goes its own way in terms of vampire lore, and this is to its advantage as well. Among other things, it is the earliest movie I know of to portray the vampire’s risen victims as both his active agents and a source of power for him. Dracula becomes bolder and more confident once Jenny has been converted, and even gains some ability to face up to a cross. The power transfer works both ways, too, for when Jenny is staked (theatrical prints showed the bloody penetration in full color, although the studio didn’t bother preserving the gimmick in the cheaply made 16mm prints they sold to TV stations), Dracula physically feels her death-throes. The Return of Dracula was also among the first to have its vampires turning into wolves (well, it’s supposed to be a wolf, anyway), a shape-shifting power with a much more ancient pedigree than the now more familiar bat transformation. (The connection between bats and vampires was not made, in Europe at least, until the 16th century, when reports of blood-drinking bats in the Americas began filtering back to the Old World.) That sort of thing combines with the unusual setting, the unexpected characterization of Dracula himself, and an atmospheric sensibility that interweaves the esthetics of late German Expressionism with those of Film Noir to help The Return of Dracula overcome a lot of its handicaps.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact