The Bad Seed (1956) **½

The Bad Seed (1956) **½

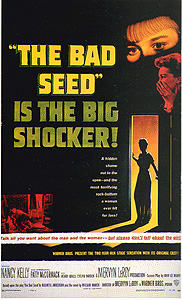

It would appear that the evil child genre as we know it today began with a little novel by William March, called The Bad Seed. Short, blunt, and often artlessly brutal, The Bad Seed is a nasty piece of work about a nasty piece of work; it’s been a favorite of mine for many years now. It can hardly be a coincidence that March’s novel arrived on the scene in 1954, just as the cultural fissures between young and old were first beginning to widen into the generation gap, but while most contemporary artifacts of intergenerational strife concerned themselves with teenagers and their newly incomprehensible and seemingly threatening ways, The Bad Seed plays for much higher stakes than fast cars and rock and roll. Its central figure is an eight-year-old murderess, whose winsome smile and impeccable manners conceal the pitiless, amoral heart of a scorpion. The cultural milieu being what it was at the time, the novel became a major phenomenon in spite of its uncompromisingly disturbing subject matter, and within a year, it had been adapted into a hugely successful Broadway play. The success of the play in turn inspired Warner Brothers to try their hand at a film version, and conventional critical opinion has it that the result was an enduring classic of suspense cinema. My opinion, predictably, is somewhat at variance from that of the conventional critics.

I’m not saying Warner’s The Bad Seed is an outright failure, mind you, but I frankly can’t see how any Hollywood studio could have done justice to the novel in the mid-1950’s. In fact, it was expressly to prevent such movies from being made that the Production Code had been written in the first place, so it was probably inevitable that The Bad Seed would be toned down and gussied up significantly so as to make it more “presentable” in the translation from print to celluloid. But of at least equal importance, Warner made a mistake which was endemic to Hollywood in those days, and turned not to the novel but to the stage play as the immediate basis for their adaptation. Consequently, The Bad Seed turned out talky, draggy, and stagebound, with a ponderously leaden midsection to compound the damage wrought by the obviously tacked-on new ending.

The Penmark family— Kenneth (William Hopper, from The Deadly Mantis and 20 Million Miles to Earth), Christine (Nancy Kelly), and eight-year-old Rhoda (Patty McCormack, who, as an adult, would appear in Invitation to Hell and Bug)— are fairly typical of the top end of the upwardly mobile middle class in 1950’s America. Kenneth is a colonel in the US Army, and his income is sufficient to support his wife and daughter in comfort, cover the rent on a stylish but modest apartment at the Tidewater Arms, and pay for Rhoda’s tuition at the self-consciously old-fashioned private school run by Claudia Fern (Joan Croydon). The Penmarks are relatively recent transplants to the area, and as yet, Christine has made no friends except for her jovially eccentric landlady, Monica Breedlove (Evelyn Varden, who played essentially the same character in Night of the Hunter); Monica’s hen-pecked brother, Emory (Jesse White); and a crime-journalist acquaintance of theirs by the name of Reginald Tasker (Gage Clark, from The Return of Dracula and The Invisible Boy). She’s about to find out just how satisfactory this small circle of friends is, too, because Kenneth has just been called out to Washington for the next month or so, leaving Christine entirely to her own devices. Naturally, this means trouble is on its way, on a scale beyond anything either Christine or her husband had previously imagined.

The source of that trouble is Rhoda. Externally, she seems like a model child. She is faultlessly polite, academically exceptional, pretty, charming, and self-sufficient to a degree that seems almost unnatural in a child her age. But she is also extremely cold emotionally, and she displays a marked acquisitive streak. Rhoda likes things, and she is not at all ashamed to ask for them— indeed, you might say that she is developing a real sense of entitlement. And while her parents do not yet realize this, Rhoda is also entirely devoid of conscience; asking for presents and favors with indecorous bluntness is the least of what she’s willing to do to get what she wants. The chain of events that will eventually bring Rhoda’s sociopathy to her mother’s attention begins with, of all things, the gold medal for penmanship which the Fern School gives out at the end of each year. Rhoda considered herself a dead lock for the medal, but it ended up going to a boy named Claude Daigle instead. (The book clarifies that the medal is awarded on the basis of improvement over the year— Rhoda unquestionably had the best handwriting, but the Daigle boy started off sloppy and finished not far short of the standard set by his rival.) The girl is understandably upset about this, but she goes a lot farther than most children in acting on her ire.

The handing out of the penmanship medal isn’t the only event that marks the end of the year at the Fern School. There is also a school picnic held at the nearby lakeside park each June, and I believe we can safely say that this year’s picnic is never going to be forgotten by any of its attendees. Why not? Because this year, the picnic is called off before it can even get properly underway when the lifeguards pull Claude Daigle’s lifeless body from the water by the old pier. There are plenty of suspicious circumstances surrounding the kid’s death, too, and all of them point to some sort of involvement on the part of Rhoda Penmark. For one thing, a guard saw Rhoda walking down the pier less than an hour before Claude’s body was discovered. For another, one of the teenage chaperones saw Rhoda chasing Claude around all morning, apparently trying to snatch the coveted penmanship medal from his shirt. Finally, Claude’s hands and forehead were marked by odd, crescent-shaped bruises, and while it’s possible that the wounds were inflicted by banging against the pier’s pilings, the highly specific pattern of their placement suggests a rather more sinister explanation. There may be no conclusive proof one way or the other, but it’s hard to fault Claudia Fern for visiting Christine Penmark a few days later and informing her that Rhoda will not be readmitted to the school for the following year.

Miss Fern isn’t the only one with suspicions, either. Hortense Daigle (Eileen Heckart, later of Burnt Offerings) soon begins making a pest of herself by showing up drunk at the Penmarks’ apartment, and trying to pump Christine and Rhoda for information she’s sure one or the other of them has. She’s especially fixated on the mystery of what became of Claude’s medal after he fell into the lake. (It was no longer pinned to his shirt when his body was recovered, and a search of the lake bottom nearby turned up no trace of it.) Meanwhile, Leroy the Tidewater Arms groundskeeper (Arachnophobia’s Henry Jones) starts pestering Rhoda by telling her he knows that she killed the Daigle boy. Really, Leroy just resents the fact that Rhoda is the only child in the neighborhood who isn’t afraid of him, and he thinks he’s finally found something to scare her with. But if he could be in the bedroom when Christine accidentally finds Claude’s medal hidden under the lining of her daughter’s jewelry box, he might get it through his thick head just how dangerous a game it is that he’s playing. But he never sees the inside of that jewelry box, and he keeps pushing the homicidal little tyke until he seals his own doom.

As I have already mentioned, the factors that prevent The Bad Seed from living up to its potential fall into two distinct categories: those imposed by the era’s censorship regime and those caused by the filmmakers retaining too much structure from the Broadway play. Of the two, the former are the more conspicuous. Enshrined within the Production Code were two clauses which were flatly incompatible with the story as William March wrote it, and as it was adapted to the stage. First, it was forbidden to show anybody getting away with a crime; second, there was an uncompromising interdict against the use of a character’s suicide to tie up a plot thread. Since March had Christine shooting herself with her husband’s pistol after giving Rhoda an overdose of sleeping pills, and the Breedloves intervening in time to make sure the child survived to kill again and again, the aforementioned rules effectively meant that the entire original conclusion had to go. It would appear, however, that this was not realized until after the scenes in question had been shot, because the movie as released to theaters does include them— it just follows them up with a new ending which re-balances the karmic scales in a most heavy-handed and unbelievable manner. Furthermore, the studio feared that even the new ending was not enough. As if to assure the audience that what they had just seen was not real, the traditional closing credits were replaced with a Broadway-style curtain call, which culminates in an absurd shot of Nancy Kelly slinging Patty McCormack across her lap and spanking her! “We were afraid the movie had turned out too good,” this three-hit combo of suck seems to say, “so we thought we’d leave you with something really stupid to take home as your final memory of The Bad Seed.”

However, I think it’s the holdovers from the stage that wreak the more damaging havoc on the film. Plays, of necessity, are generally tightly contained, spatially speaking. For simplicity’s sake, a small number of sets is a must, and the more of the action you can confine to a single room, the better. There isn’t the same pressure to go that route in a movie, however, and when a filmmaker does it anyway, the effect is extremely conspicuous. In the case of The Bad Seed, entirely too much time is given over to people sitting around and talking in the Penmarks’ living room. Indeed, in the midsection of the film, it feels as though we spend an hour at a stretch looking at the same three people having the same two anguished conversations while sitting on the same two sofas surrounded by the same four walls. At 129 minutes, The Bad Seed could have used a bit of streamlining as it was, but the boxed-in quality of the second and third acts magnifies the problem considerably. It also may not have been such a good idea to reuse so much of the Broadway cast. All the major players had been transplanted from the stage, and their acting is much too artificial for a movie. Most of them were nominated for industry awards anyway, and Eileen Heckart actually won hers, but unless, for example, Nancy Kelly were honored with a special Oscar for Longest Continuous Onscreen Weeping Fit, the adult Broadway transplants scarcely deserved such recognition.

It says a lot about the strength of March’s original story that The Bad Seed often works in spite of all those handicaps, and it says even more about the effectiveness of Patty McCormack’s performance. She fumbles frequently enough, to be sure (it looks to me like she’s trying to copy the stilted effusiveness of Nancy Kelly and Evelyn Varden), but when she relaxes and plays it natural, she’s absolutely chilling. There are few films of this vintage that contain anything as disturbing as Rhoda riding off on her roller skates and scoffing at Leroy’s reproachful observation that she isn’t at all sorry about what happened to Claude: “Why should I be sorry? It was Claude Daigle who drowned, not me!” To some extent, you have to pity an actress with as long a career as McCormack’s, who nevertheless hit her professional peak at the age of eleven, but at the same time, it’s hard to imagine anybody living down a role like this one, no matter how long they spent in the Hollywood trenches thereafter.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact