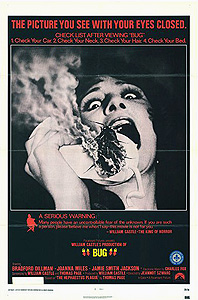

Bug/The Bug (1975) ***½

Bug/The Bug (1975) ***½

William Castle had been more or less all washed up as a director since the late 1960’s, when Paramount’s leadership refused to let him direct Rosemary’s Baby— a project for which he had done just about all the hard work of pre-production development— and handed it over to the up-and-coming Roman Polanski instead. Castle continued to soldier on as a writer and producer, however, and it wasn’t until 1975 that he finally faded from the scene completely. The final film to which he contributed was this obscure oddity directed by Jeanot Swarc. Bug/The Bug, based on Thomas Page’s novel, The Hephaestus Plague, is an unassuming picture, which at first glance could easily be mistaken for one of those made-for-TV horror films that the 1970’s spawned by the truckload. But to those who are willing to give it a fair chance, it offers an unexpectedly compelling character study in psychological breakdown, one of the most scientifically credible treatments of the ever-popular prehistoric-monsters-from-the-inner-Earth theme yet committed to film, the most effective use of live insects I’ve ever seen in a horror or sci-fi movie, and even a few genuinely creepy scare scenes.

The film opens with a church service in a small desert hamlet being disrupted by one of the earthquakes that so often make life difficult for the residents of southern California. It quickly becomes clear that the days and weeks to come will bring something more dangerous than aftershocks, however, because several of the fleeing parishioners are killed when their vehicles explode for no readily apparent reason. Among those barbecued to death in their cars are the parents of Tom and Norma Tackler (Jesse Vint, from Pigs and Forbidden World, and Jamie Smith-Jackson, from House of Evil and Satan’s School for Girls, respectively), and by an unfortunate twist of fate, the crack in the earth opened up by the quake passes straight through one of the fields on their family farm. No one realizes this yet, but the effects of this crack go beyond its obviously detrimental effect on the Tacklers’ property values, and the depth of its consequences for their lives will rival even that of their parents’ deaths. In fact, we shall soon see that there is a strong connection between the two. While Norma and her boyfriend, Gerald Metbaum (Richard Gilliland), inspect the crack, they are too overawed by the spectacle of a rift in the earth to notice the large, strange insects crawling slowly over the ground all around them, but make no mistake, these creatures will make their presence felt soon enough.

Gerald first sees the cockroach-like bugs that night, while having another look at the fissure. To his astonishment, one of the insects burns his fingers when he tries to pick it up. Then, before his horrified eyes, another of the bugs retaliates against the molestations of the Tackler family cat by burning the unfortunate animal to death. It and several of its fellows begin to feast on the cat’s charred flesh once the animal’s struggles have stopped. Something like that is simply too weird to be ignored, and Gerald goes back to his old college the next day to ask biology professor James Parmiter (Bradford Dillman, of The Mephisto Waltz and Escape from the Planet of the Apes) if he knows anything about fire-making roaches. Parmiter doesn’t take Gerald terribly seriously at first, but he changes his tune after he’s had a look at what’s left of the cat, and he accompanies his former student to the Tackler farm immediately thereafter to collect specimens.

Needless to say, the “firebugs” are like no insect species Parmiter has ever seen before. To begin with, the thorny, chitinous appendages on their abdomens, which they rub together to create fire in much the same way as a camper rubbing two dry twigs together, are completely unique in the animal kingdom. (Note that there seems to have been a communication breakdown between screenwriter Castle and the special effects department— though Parmiter explicitly states that the firebugs do their special trick with friction, what we see on the screen just as clearly depicts them using electricity to achieve the effect.) The rest of their physiology is equally strange, though. They lack any kind of conventional digestive system, and subsist on a strict diet of carboniferous ash, which is digested for them by the colonies of symbiotic bacteria that occupy the space in their bodies that would ordinarily be filled by their guts. Strangest of all, every firebug Parmiter and his colleague, Dr. Mark Ross (Alan Fudge, of Brainstorm and My Demon Lover), examine seems to be suffering from the same serious illness. All the insects are sluggish, are breathing far too laboriously, and exhibit no interest in mating. Parmiter soon puts the pieces together— the firebugs are creatures from the depths of the Earth, having evolved since Devonian times to fit an environment of extreme heat and pressure. It was the recent earthquake that brought them to the surface, and that’s why they can be found in the greatest numbers in the vicinity of the crack in Tackler’s Field. The reason they seem sick is that pressures and temperatures are too low for them up on the surface— they’re freezing to death, and they’ve all got the bends!

The firebugs’ infirmity doesn’t stop them from making a nuisance of themselves, though. Spreading out across the countryside by hitching rides in automobile tailpipes, the insects begin causing death and destruction on a scale large enough that no one but Parmiter thinks to look for the cause in something so lowly as a plague of insects from the Earth’s mantle. The one consolation is that the creatures’ reign of terror is sure to be brief, as they cannot long survive under the conditions they find above sea-level. For Parmiter, however, that is no consolation at all; one of the firebugs’ last victims is his wife, Carrie (Joanna Miles, from The Ultimate Warrior and The Orphan).

This is where James Parmiter and his sanity part company. Following his wife’s death, he develops an obsessive need to understand the creatures that killed her. He has Gerald (an engineer) build him a makeshift pressure tank out of an old deep-sea diving helmet, so that he can provide his last living firebug with an environment in which it can live and be studied. Finally, Parmiter hits upon the idea of mating the firebug with what seems to be its closest terrestrial relative, the common American cockroach. He figures the resulting hybrids will be able to survive outside the pressure tank while still retaining enough similarity to the original firebugs to make studying them worthwhile. This is, of course, a disastrous error in judgement, and the new firebug-cockroach crossbreeds (which James dubs Parmitera hephaestus) provide a truly horrifying illustration of the concept of “hybrid vigor,” while Parmiter naturally meets with the fate traditionally prescribed for all men of cinematic science who spend their off-hours making monsters.

My favorite thing about Bug is that it’s really two movies in one. The first half of the film is a good old-fashioned monster rampage on the 50’s model, but is marked by an altogether exceptional degree of scientific rigor. It has its credulity-straining moments, but on the whole, it is a thoughtful and quite plausible examination of what might happen if a new species from an utterly alien environment were introduced into our world. Then, the movie shifts gears to chart James Parmiter’s descent into insanity and obsession, pitting its increasingly unstable protagonist against the increasingly powerful foe that he creates for himself in the Parmitera. Bradford Dillman puts in an admirable performance in this phase of the film, hitting the mark directly on the complicated harmony of negative emotions that underlie his character’s collapse. Meanwhile, Swarc rises above the flat, TV movie-like feel of the first half, and succeeds in investing the Parmitera with an aura of menace drastically out of proportion to anything that a box full of cockroaches ought to be capable of evoking.

And that leads me to the smartest decision the creators of Bug made. Until the very last scene, in which some ill-considered details of the script force the filmmakers to use some extremely cheesy plastic models, all of the insects in Bug are the real thing. I have no idea what species of cockroach was used to portray the otherworldly-looking firebugs, but the Parmitera are really the formidable Madagascar hissing cockroach (I once read an article in which this species was described as resembling “an armored stretch limo,” and that’s not too far from the mark), and in the long-distance shots, the flying, second-generation firebug hybrids are the famous Florida palmetto bugs. The use of real roaches, of species with which comparatively few Americans are likely to be familiar, lends a vital air of realism to the movie, making the more outlandish twists of the plot far easier to swallow than they would have been had rubber bugs of one sort or another been used instead. And considering the extraordinary levels of loathing and disgust that cockroaches inspire in most people, the loving attention Swarc’s camera pays to his cast of armor-plated, four-inch-long roachzillas seems sure to make watching Bug, for many, a harrowing experience indeed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact