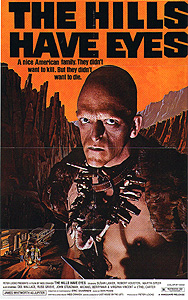

The Hills Have Eyes (1977) *****

The Hills Have Eyes (1977) *****

Wes Craven’s career has been an uneven one, even by the erratic standards of other star directors in the horror field. On the one hand, he brought us A Nightmare on Elm Street (the only supernatural slasher movie you really need) and Scream (not the work of genius it’s been hailed as, but still the best teenagers-vs.-maniacs flick in most of a decade). On the other hand, Craven was also responsible for turkeys like Vampire in Brooklyn, and a string of dismal made-for-TV horror films including the absolutely soporific Invitation to Hell. And in contrast to the careers of many filmmakers, it isn’t even possible to detect a real trend in quality among Craven’s movies, one way or the other— The Serpent and the Rainbow, maybe the most effective voodoo movie since the 30’s, stands bracketed between the contemptible Shocker and the utterly abysmal Deadly Friend. All told, Wes Craven might best be described as “fitfully brilliant,” with the stipulation that, when he fails, he tends to fail spectacularly. But while I’m sure I’ll get around to one of those spectacular failures eventually, I’m equally sure we’d all rather I let the man make his first appearance in these pages with one of the good ones. So, then— the finest movie about cannibals ever made by an American director, the pinnacle of Craven’s career, and one of my five favorite horror flicks of all time, The Hills Have Eyes.

Lots of people have talked about the incredibly versatile and virtually sure-fire atmospherics of the American Southwest. Few environments on Earth can match the Southwestern desert’s combination of tranquility and menace, of beauty and hostility, or compete with that region’s imperious air of nature’s sheer indifference to the concerns and requirements of human life. It’s a great place to set a movie, because only the most incompetent cinematographer can fuck it up, and in the hands of people with real talent, a well-chosen desert setting can hugely multiply the impact of the goings-on onscreen. Don’t believe me? Then just have a look at the slow pan across the craggy, rubble-strewn, iron-bearing desert hills at dusk that plays beneath The Hills Have Eyes’ opening credits. The text on the screen may be little more than a bunch of mostly unfamiliar names, but what that credits sequence is really saying is, “Hi. I’m Wes Craven, and I’m going to kick your ass.”

The script then drops us shrewdly into the middle of something we don’t understand, but instinctively know is bad news. An old man named Freddy (John Steadman, from The Unholy Rollers) is puttering around outside his forlorn edge-of-nowhere gas station/general store when he is snuck up on by a teenage girl with a sack full of junk. The girl’s name is Ruby (Janus Blythe, of Eaten Alive and The Incredible Melting Man), and it seems she’s Freddy’s granddaughter. She and Freddy talk about trading Ruby’s sack of random crap for food and bullets, about how Freddy plans to close up shop and move away to someplace less isolated, and about how somebody named “Papa Jupiter” is going to be very upset if he finds out that the old man means to skip out on the run-down old store. There’s also some worrisome business from Freddy about the Air Force sending MPs into the desert to hunt down “you coyotes.” Suddenly, Fred is struck by a realization— Ruby wants to get away too, and she’s hoping her grandfather will take her with him! Freddy doesn’t think this is a good idea; not only will the mysterious Papa Jupiter be just as pissed about Ruby’s desertion as he will about the old man’s, the girl’s social skills are apparently seriously wanting— “Why, you don’t know a knife and fork from your own two hands, and you smell like a horse!”

But before any final decision can be reached, the pair’s conversation is interrupted by the arrival of the Carter family’s station wagon and trailer home at Freddy’s shop. The Carter patriarch is a newly retired cop named Bob (Russ Grieve, from Dogs and Foxy Brown). He, his wife, Ethyl (Virginia Vincent, of The Baby and The Return of Dracula), and his teenage offspring, Bobby (Robert Houston, from Cheerleaders’ Wild Weekend and Strange Behavior) and Brenda (Susan Lanier), are on their way west to California; their eldest daughter, Lynn (Dee Wallace, of The Stepford Wives and The Howling— the closest approach to a name actor we’ll be seeing), and her husband, Doug Wood (Martin Speer), are also along for the ride with their infant daughter, while two German shepherds named Beauty and Beast finish out the trailer’s compliment. The reason the Carters are so far off the beaten track is that Bob has inherited the title to an old silver mine out in the Nevada desert, and he wants to have a look at it before moving on to the family’s real destination. Freddy tells the Carters not to bother; the silver in the mine dried up decades ago, and the closest thing to a human settlement out in that part of the desert is an Air Force bombing range. If the Carters are asking Freddy, they should head straight back to the interstate, and continue on to California by the direct route. Thanking Freddy for the gas and the advice— which they have no intention of following, mind you— Bob and his brood drive off down the increasingly ill-repaired road into the increasingly desolate countryside. And in doing so, they just miss the show when Freddy’s pickup truck explodes into an immense ball of flame. Looks like the old man won’t be pulling up the stakes any time soon, after all...

But getting back to the Carters, Bob’s foolhardy quest for his extinct silver mine has taken them off of any road that appears on their map, and the gravel track they’re currently following leads straight into that bombing range Freddy warned them about. Everybody else in the car figures out pretty quickly that they’ve gotten themselves lost, but stubborn old Bob doesn’t believe it until a low-flying F-105 Thunderchief streaks across the sky above them at just below the speed of sound. In the resulting confusion, Bob loses control of the station wagon and drives clear off the road, snapping the car’s rear axle on an especially sharp boulder. Freddy isn’t the only one who won’t be going anywhere now. The inherent hostility of the desert is the least of the Carters’ worries, though, because somebody is watching them from the surrounding hills, talking among themselves about the stranded family’s plight over military surplus CB radios. And judging from the way they’re talking, helping the Carters out of their fix isn’t on those people’s agenda.

Bob Carter swiftly concludes that there’s nothing for it but to walk back to Freddy’s gas station and call for help. And while he’s running that errand, he sends Doug off in a perpendicular direction to see if he can find the base that Air Force fighter-bomber operates out of. The ex-cop leaves Bobby with one of the two pistols he brought with him on the trip, and tells everyone that the boy is in charge until he and Doug return, which, given the length of the journeys ahead of them, probably won’t be until well after sunset. This is about when those watchers in the hills begin making their presence felt. The two dogs have been on edge from the moment the car came to a stop, and Beauty manages to break away from Bobby, running off into the arid hills. Bobby chases after the dog, but by the time he finds her, someone or something has slit her belly open, and left her lying in the burning sand surrounded by her own entrails. Whatever killed Beauty lunges at Bobby a moment later, but by that time, the boy is too busy running back to the crippled trailer to see just what it is. Beast runs off, too, around dusk, and for the next several hours, the predators in the hills torment the Carters by mimicking the whining of an injured dog, alternating at strategic moments with an amazingly broad— and ecologically impossible— range of other animal noises, just to make sure Bobby knows that whatever’s stalking his family is at least biologically human. Doug’s return from the vicinity of the Air Base brings little encouragement; the only section he could find within reasonable walking distance appeared to be completely deserted.

Meanwhile, Bob makes his way back to the gas station, and has a very strange encounter with Freddy. The two men play an armed game of cat and mouse for the first few minutes after Bob arrives at the place, and when Carter finally corners his opponent, he finds him trying to hang himself from the rafters with his own belt. “I thought you were someone else,” the old man cryptically explains. Bob obviously wants to know just who he’d been mistaken for, so Freddy pulls out a bottle of rotgut booze and sits him down for a little story. It seems Freddy didn’t always live alone. When he first came to this godforsaken corner of the desert in 1929, he had his little daughter and his pregnant wife, Martha, along with him. The baby Martha was carrying was, to say the least, not quite normal. To begin with, he was huge— nearly 20 pounds at birth, and as big as his father by the time he was ten years old— and he “came out sideways”; his mother, needless to say, did not survive the experience. And Jupiter, as Freddy named his freakish son, was as aberrant psychologically as he was physically. He killed animals for fun— with his bare hands and even his teeth— and simply could not be socialized to fit in with other people. Then one day, while Freddy was at work, Jupiter burned down the house with his sister in it. Freddy went a little nuts when he saw that. He smashed the boy’s face with a tire iron, and left him out in the desert to die. Now Bob, apparently, is a rather dense man, and he doesn’t quite see the point of Freddy’s story— “But that was a long time ago,” he says. The old man agrees: “Time enough for a devil kid to grow up to be a devil man! Time enough for him to steal a whore nobody’d miss and raise a passel of monster kids of his own!” Just then, a huge man with a distinctive, deep scar down the center of his face (James Whitworth, from Sweet Sugar and Planet of the Dinosaurs) lunges through the window, grabs Freddy, and pulls him out into the night. Bob gets his turn just a few minutes later.

The rest of the Carter family meets Jupiter and his brood after another hour or two. The patriarch of the savages crucifies Bob to a big mesquite bush, rigs his body with firebombs, and then uses him to get Bobby and Doug’s attention. With all the men thus occupied, Jupiter’s sons, Mars (Lance Gordon) and Pluto (the unforgettable Michael Berryman, whom Wes Craven liked enough to hire again for Deadly Blessing and Invitation to Hell), attack the women in the trailer, while his youngest boy, Mercury (Peter Locke), keeps watch from the nearest ridge. Mars and Pluto gut-shoot Ethyl and Lynn, and attempt to rape Brenda before Doug and Bobby figure out what’s going on back at the trailer, and though the two brute-men are chased off, they carry away most of the Carters’ food and ammunition— and Doug and Lynn’s baby— with them. In the ensuing all-out war between the two families, the remaining Carters are going to have to learn to be as vicious as Jupiter and the cannibals if they’re going to stand the slightest chance of survival.

Some people are going to look at The Hills Have Eyes and see only the primitive production values, the non-professional cast, and the lack of glossy, elaborate gore effects. Those people are to be pitied. They’re like the Danzig fans who can’t appreciate the Beware-era Misfits because they can’t get past the old records’ junky, low-fi sound quality. This is a movie about deformed cannibal mountain men, for God’s sake! If it were as slick and glossy and thoroughly polished as something like Scream, it wouldn’t have a hundredth of its current impact. That raw, gritty, primitive immediacy is The Hills Have Eyes’ greatest strength. With production value only a few steps up from what you’d expect of a Bolivian snuff film, the distancing effect that comes naturally with all the usual Hollywood varnish is totally absent here, and the Carter family’s peril seems far more real than it would if the film had been made according to modern big-studio practices. This is doubly important in this case because of Craven’s utter refusal to pull any of his punches or allow his audience any ground on which they can feel safe. Not only does the usual rule that no dog can ever be killed in a horror movie not apply here, when Mars and Pluto run off with that baby, there’s no reason in the world to believe they won’t be eating her later on! Furthermore, all of the characters here are written like real people— I’ve personally known someone who reminded me of every single member of the Carter family— and when they die (and a lot of them do), it really does matter. A lot has been written about The Hills Have Eyes’ deeper psychological themes, most notably the “all people are savages when they need to be” angle, but I’m not going to go into that sort of thing here. Mainly, this is because watching The Hills Have Eyes for the first time is too awesome an experience for me to want to ruin it by cutting the film open and pointing out how every little muscle, organ, and nerve fiber works. But it’s also because one needn’t even dig that far in order to feel this movie’s power. There’s more at work right on the surface of things than can be extracted from most other horror movies with all the bullshitting might at a film-school professor’s command.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact