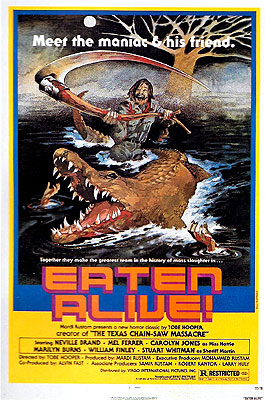

Eaten Alive / Death Trap / Brutes and Savages / Horror Hotel Massacre / Horror Hotel / Legend of the Bayou / Murder on the Bayou / Starlight Slaughter (1976) **

Eaten Alive / Death Trap / Brutes and Savages / Horror Hotel Massacre / Horror Hotel / Legend of the Bayou / Murder on the Bayou / Starlight Slaughter (1976) **

We’ve talked before about Tobe Hooper’s undeserved reputation as a one-hit wonder, about how he spent most of his career being the Guy Who Never Lived Up to the Promise of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, even as solid pictures like Salem’s Lot, Poltergeist, and Lifeforce accumulated under his byline. I’ll grant you that nothing I’ve seen of Hooper’s subsequent work ever equaled his magisterial debut, but just the same, it seems odd that horror fandom as a whole was so hard on him all those years. It starts to make sense, though, once you see Hooper’s second feature, Eaten Alive. Talk about sophomore slumps! Despite a B-movie dream cast and an interesting, prescient visual sensibility, Eaten Alive was never going to come as anything but a disappointment to fans fresh from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It’s a shambling, shapeless exercise in time-killing, with no clear point and no apparent appreciation for its own best features. I didn’t find it as totally worthless as I’d been warned to expect, but if I’d seen it in its original release, my reaction would definitely have been something along the lines of, “What kind of bullshit is this?!?!”

Clara Wood (Roberta Collins, from Saturday the 14th and Wonder Women) simply isn’t cut out to be a whore. Even when her johns are handsome and enthusiastic like Buck here (Robert Englund, of A Nightmare on Elm Street and The Mangler), the poor girl can barely stand to let them touch her, and anything even a little bit kinky sends her to the verge of hysterics. The mutiny Clara stages when Buck announces his intention to fuck her in the ass is the last straw for Miss Hattie (Carolyn Jones, from Invasion of the Body Snatchers and House of Wax, unrecognizable beneath ghoulish and rubbery old-age makeup), the proprietress of the cathouse where she notionally plies her trade. Miss Hattie sets Buck up with a substitute (plus a second girl on the house), then sends Clara packing. On her way out the door, Clara is accosted by Miss Hattie’s housekeeper, who always liked and took pity on her; she gives the girl ten dollars, enough to rent a room for the night at a skanky bayou flophouse called the Starlight Hotel.

Some favors are better left unbestowed. The Starlight is a lonely, eerie, menacing sort of place, which is only rendered more so by the star attraction at the “zoo” which the proprietor (Neville Brand, of Without Warning and Killdozer) attempts to lure passing curiosity seekers: a huge crocodile whose fenced-in pond comes right up to the edge of the hotel’s porch. Mind you, the owner is no bundle of joy himself. An irascible old man with spectacularly poor hygiene and a prosthetic leg, Judd looks like trouble when you meet him for the first time, then looks ever more like trouble with each subsequent second you spend in his company. He mutters to himself constantly, his conversation is full of disturbing non-sequiturs, and if anybody ever had the Evil Eye, it’s this guy. If Clara could afford to stay anyplace else, she surely would. And worse luck, Judd recognizes her while showing her to her room. Evidently he’s been around to Miss Hattie’s a time or two himself since Clara hung up her shingle there, and now that he knows his new customer is a whore, he feels entitled to take part of the night’s rent out in trade. That’s just what Clara was trying to escape, so naturally she doesn’t cooperate. Judd, apparently not one to take snubbing lightly, kills Clara and feeds her to the crocodile.

An indeterminate amount of time later (anything from half an hour to a month and a half seems equally likely), a very odd family checks into the Starlight. The woman is called Fay (Marilyn Burns, from Sacrament and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), the man is Roy (William Finley, of Sisters and The Fury), and the little girl is Angie (Kyle Richards, from Watcher in the Woods and The Car). Fay is clearly in charge here, projecting an image somewhere between financial sector dragon lady and professional dominatrix. Also, she seems somehow to be in disguise— although I guess she could just be one of those women who put great stock in affecting separate public and private personas. Either way, she looks like an entirely different person when her lustrous black wig and severe Fifty Shades of Theresa May suit come off. Ray is either the most neurotic person I’ve ever seen, or a lifestyle sub for whom literally everything is an opportunity to indulge his kink. Maybe he’s both. And Angie is extremely high strung and given to positively Byronic tantrums, but she looks relatively normal in comparison to her parents. Also, Byronic tantrums are arguably called for under the present circumstances, since Angie’s first impression of the Starlight Hotel comes when Judd’s crocodile eats her dog. That’s about as good as this night is going to get for her, too. Just barely has the family settled in before Judd kills Roy, ties Fay to the bed in their room, and chases Angie into the crawlspace under the hotel.

Judd’s next customers threaten to be real trouble. Their names are Harvey (Mel Ferrer, of Blood and Roses and The Pajama Girl Case) and Libby (Crystin Sinclaire, from Caged Heat and Hustler Squad) Wood, and they’re the father and sister respectively of Clara. Evidently the girl ran away from home, and her relatives have been searching for her ever since. When Harvey shows Judd a photo of Clara, the old loony lets slip that he recognizes her from Miss Hattie’s brothel before he fully wraps his mind around the likely implications of the question. That sends the Woods tearing off to see Sheriff Martin (Stuart Whitman, from Invaders of the Lost Gold and Night of the Lepus), which is obviously bad news for a guy who has a woman tied up in his hotel, a child trapped underneath it, and the remains of two human beings in the crocodile pit out back. And as if that weren’t complication enough for the reclusive madman, Buck (who looks like he may be Judd’s ne’er-do-well son once we get a chance to watch them interact) brings a floozy (Janus Blythe, from The Hills Have Eyes and Drive-In Massacre) around with an eye toward availing themselves of one of the Starlight’s beds. That’s way too many people in a position to discover way too much, but it’s also too many for Judd to knock off safely. I mean, how much can one crocodile eat in a night?

The galling thing about Eaten Alive is that it puts all the pieces of a more interesting movie on the table, but then sets them aside having just barely played with any of them. I’m talking about Fay, Roy, and Angie, a collection of loose screws that initially seem to promise something like an American In the Folds of the Flesh, but with Paul Bartel’s sense of humor. For a glorious handful of scenes, Marilyn Burns and William Finley tease us with implications of lunacy beyond anything we could plausibly expect from Judd, with his slow wit and senile simplicity. A nightmare of weaponized gender politics, passive-aggressive masochism, and parallel-universe parenting, what we see of Fay and Roy’s misshapen marriage is at once blackly funny and genuinely disturbing. If only they, and not the insipid Wood family, had been the focus of the picture! I would much rather have watched “psycho family takes room at psycho hotel; hilarity ensues” than just another pedestrian riff on Psycho. Makes it hard to evaluate the film strictly on its own merits, you know? Especially when those merits are so slight to begin with.

Eaten Alive has these two little plot circles, and it spends most of its 91 minutes going around and around in them, pausing only to shift from one to the other. In the first circle, a guest shows up and does or says exactly the wrong thing, after which somebody gets fed to the crocodile. In the other, Judd takes a crack at extracting Angie from her hiding place under the hotel. Neither ever amounts to much on its own, beyond running out the clock until it’s time to give Judd his comeuppance. That’s boring in and of itself, but it also causes problems by leaving us with neither any one victim to root for against Judd, nor a group of survivors to form an ensemble for the final act. The latter is closer to what actually happens, but Eaten Alive’s conclusion is missing the part where the participants come together. It’s more that they’re all sort of in the same place at the same time when Judd finally becomes croc chow.

Against all that, the main thing that Eaten Alive has to show for itself is a visual aesthetic most of a decade ahead of its time. All the way back in 1976, Tobe Hooper anticipated the look of mid-80’s horror films— the return of stylization and contrived atmospherics not only to movies premised on the fantastic, but to those of thoroughly mundane subject matter as well. Inside and out, the Starlight Hotel looks like something even more sinister than a murderer’s lair. The use of minimalist soundstage sets for the supposed exteriors gives the place a disquieting unreality, especially in combination with the forthrightly unnatural lighting schemes that Hooper uses on it. It’s almost as if the hotel were at the bottom of some kind of cosmic cul-de-sac, from which there may or may not be any way out. The interior sets aren’t as stylized, but there’s still a strange, unfinished quality to most of the Starlight’s insides. That’s quite a change from the agonizingly immersive realism of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Nevertheless, it could have been just as effective in its way. It simply required Eaten Alive to be a better movie in other respects.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact