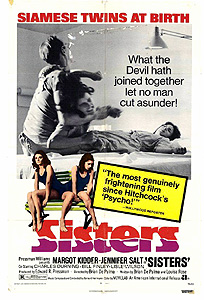

Sisters/Blood Sisters (1973) ***½

Sisters/Blood Sisters (1973) ***½

Sisters was the picture that redefined Brian De Palma’s career. He had been making movies since the mid-1960’s, when a string of experimental shorts culminated in the experimental feature Murder a la Mod, and his earliest professional feature films were a series of strange, counterculturey comedies. Sisters, although its plot also reuses some elements from Murder a la Mod, marked De Palma’s first major effort in the Hitchcockian mode that would figure so strongly in his output throughout the later 1970’s and into the 1980’s. That said, it would be a major oversimplification to dismiss Sisters as a mere Hitchcock copy; this movie is something much stranger and much more interesting than that. It’s more like what might happen if Hitchcock had died while directing a film from a script by David Cronenberg, and Paul Bartel had been hired to complete the project.

We start out with a meet-cute of the rare sort that really is about as amusing as it’s cracked up to be. Phillip Wood (Lisle Wilson, from Cotton Comes to Harlem and The Incredible Melting Man) and Danielle Breton (Margot Kidder, of Black Christmas and The Reincarnation of Peter Proud) are brought together by the TV show “Peeping Toms,” which is sort of like a cross between “Candid Camera” and “Family Feud.” Camera crews secretly film unsuspecting innocents being placed in flustering setups, and the contestants have to guess how they dealt with the situations. Then the participants in the setup are brought onstage to talk a bit about the experience and to be rewarded with some manner of prize. In Wood’s case, he was in the locker room at the gym when Breton, a Quebecois model whom “Peeping Toms” had hired to pose as a blind girl, wandered in (ostensibly having mistaken the men’s locker room for the women’s) and began undressing right in front of him. After they’re dismissed from the studio portion of the episode’s taping, Danielle asks Philip out, suggesting that he might like to cash in his prize (a free dinner for two at the Africa Room) that night. The evening hits its first odd note when Philip and Danielle are interrupted by the woman’s ex-husband, Emil (William Finley, from The Phantom of the Paradise and The Funhouse). According to Danielle, they split up a year ago, but Emil just can’t let go, and continues to follow her all over the place, interfering with her life. Wood summons the head waiter, and has Emil evicted from the restaurant. Even so, Danielle thinks she would prefer to be taken home now— although Phillip is welcome to hang out for a while at her apartment.

In fact, Phillip spends the night there, although he first has to make a show of leaving in order to drive off Emil, who parks himself outside the door to Danielle’s building, in a position from which he can comfortably spy on them through the windows. Once the action begins, Phillip either somehow fails to notice or is simply not put off by the horrid, furrowed scar that covers nearly the whole of the girl’s right hip, and a good time is had by all. The next morning, Phillip hears Danielle arguing in French with another woman while he gets himself cleaned up and dressed. Shortly thereafter, Danielle explains that it is her birthday, and her twin sister, Dominique (also Margot Kidder)— who is extremely difficult, and perhaps slightly unbalanced— is in town to celebrate. (Wait— twin sister? Ghastly scar? You wouldn’t happen to see any great, big wicker baskets lying around the apartment, would you, Phillip? You should check that out. It might be kind of important.) Then she asks him to run an errand for her. Danielle is on some kind of prescription meds, and she doesn’t have but two pills left— would Phillip mind running down to the drug store, and getting the prescription refilled? Not a problem. And while he’s at it, Wood spontaneously decides to stop at the bakery a few doors down, and pick up a birthday cake for the twins. The delay is a significant one, because Danielle actually has none of her drugs left at all; she had set her last dose down on the rim of the sink before Phillip went into the bathroom to shower, and he knocked the pills down the drain without realizing that they had been there in the first place. Danielle begins having some kind of seizure while the lady at the bakery is writing “Happy Birthday, Dominique and Danielle” on the cake in icing, and she has just enough time to phone Emil for help before she falls to the bathroom floor unconscious. When Philip returns with the pills and the cake, he doesn’t see Danielle, but there is somebody (presumably Dominique) asleep on the fold-out sofa in the living room. Phillip lights the candles on the cake, brings it to the sofa along with a knife that seems just a little unnecessarily formidable for cutting it, and awakens Dominique. She grabs the knife, stabs him in both femoral arteries, and chops the hell out of his back once he’s helpless on the floor. Then she wanders off somewhere. Phillip just manages to crawl to the kitchen window and get the attention of one of the neighbors before he dies, scrawling the word “help” on the glass in his own blood.

That neighbor is Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt, of Gargoyles), and she’s a columnist for a second-rate newspaper called the Staten Island Panorama. Grace immediately calls the cops to report a murder in the unit across the courtyard and a floor down from her own, but she is not a popular woman around the station these days because of a story she wrote on the subject of police brutality and violations of civil rights. Something tells me that entitling the column “Why We Call Them Pigs” goes a long way toward explaining the hostility that greets her now. It takes Grace a very long time to convince Detective Kelly (Dolph Sweet, from Death Moon and Colossus: The Forbin Project) that she is neither pulling his leg nor imagining things, and during that delay, Emil arrives at Danielle’s apartment. He’s horrified to learn that Dominique is in town, and more horrified still once he gets a look at what she’s left in the kitchen. Interestingly, there’s no sign of the killer twin herself in the flat at the moment. While Grace argues with Kelly over the phone, Emil takes charge of cleaning up the apartment and getting Phillip’s body hidden (he stashes it inside the fold-out couch); Emil even has time to run out and begin making arrangements for the corpse’s permanent disposal. Danielle’s flat therefore looks very little like a crime scene when Kelly and his partner finally arrive, and when Collier finally convinces them that rushing to the victim’s aid is more important than taking her statement. Nobody notices the one small bloodstain that Emil missed, and Grace ends up looking like a fool.

Collier knows what she saw, however, and while Kelly may consider the case closed, she most assuredly does not. She calls her editor to promise him a hard-hitting story about racist cops refusing to investigate the murder of a black man, and then sets about solving the mystery herself. First she hires a private detective named Joseph Larch (Charles Durning, of The Fury and When a Stranger Calls) to help her stake out the Breton girl’s apartment. After ascertaining that Danielle is off at work, Larch breaks in, and he doesn’t have to look very long before the immense weight of the piece convinces him that the man Grace saw murdered is hidden inside the sofa. He also finds a something very curious in Danielle’s bedroom— a patient file from a special clinic called the Loissel Institute. Unfortunately, Emil arrives just minutes later with a team of movers to haul the incriminating sofa away, and Larch only narrowly avoids getting caught. He hastily tells Grace what he found after making his escape, leaves the file folder with her, and then drives off in pursuit of the moving van— it wouldn’t do to lose track of the key piece of evidence, now would it? Taking a closer look at the folder from Danielle’s bedroom, Grace observes that it details the case history of the Blanchion twins, the first known pair of conjoined twins to be born in Canada; she remembers reading about them in Time Magazine a little over a year ago. What she had forgotten, however, was the girls’ first names: Danielle and Dominique. Fascinated by the possibility that her murder suspect might really be a famous former Siamese twin living under an assumed name, Grace pays a visit to reporter Arthur McLennan (Barnard Hughes, from Tron and The Lost Boys) at Time headquarters to pick his brain for information on the Blanchion girls. From McLennan, Collier learns that the doctors who cared for the twins after their parents died in an accident considered their conjunction too delicate to be separated safely, and that Dominique Blanchion had a reputation for mental instability. Nevertheless, they were indeed separated shortly after McLennan last interviewed them; the voiceover in the video McLennan shows Collier enigmatically states that “nature” forced the doctors’ hands. Even more interestingly, the same video plainly shows Emil at the Loissel Institute— not as Danielle’s husband, but as one of the twins’ doctors. But the most unexpected detail of all is one that McLennan learned off the record from one of the nurses who assisted in the detachment surgery. If that nurse is to be believed, Dominique, regardless of all manner of reports to the contrary, died on the operating table. Armed with that information, Grace decides that the time has come to start keeping close tabs on both Danielle and Emil. Eventually, she follows them both to a recently opened experimental halfway house for the mentally ill in her mother’s neighborhood, where her life suddenly turns into something Franz Kafka might have dreamed up.

What often gets lost today in any discussion of Brian De Palma’s movies is how funny he was capable of being back before he had a reputation to maintain as a Serious Artist. Sisters isn’t quite as mordantly humorous as the slightly later The Phantom of the Paradise, but it can nevertheless laugh at itself without the slightest embarrassment. The “Peeping Toms” telecast with which the movie opens does for early 70’s television what Paul Verhoeven would do for its 80’s counterpart in RoboCop, and does it every bit as well. The scenes with Grace’s mother (the main function of which is to sneak vital exposition in through the back door) have a wonderful comedy-of-manners quality about them, with the “modern,” “liberated” Grace exasperatedly chafing against her old-fashioned mom’s utter cluelessness about the sort of life Grace wants for herself. With the home life those vignettes reveal, it’s no wonder Collier spends so much of the movie trying to tell other people (some of whom need her advice, and some of whom definitely do not) how to do their jobs, and her pushiness becomes as amusing to the audience as it is vexatious for the other characters. Finally, De Palma has even come up with a clever and engaging way to use one of the most irritating filmmaking fads of the late 60’s and early 70’s, the split-screen counterpoint. Grace’s dickering with Detective Kelly is juxtaposed against Emil’s efforts to make Danielle’s apartment presentable after Phillip’s murder, and De Palma somehow manages to make it work as both suspense and high farce simultaneously. In addition, he plays a neat little split-screen trick at the beginning of the sequence that very efficiently explains how Collier became persona non grata with the police force; while she talks first to the police receptionist and then with Kelly in one frame, a succession of her column headings appears in the other, with “Why We Call Them Pigs” coming up at the very moment that Collier gets sidetracked justifying herself to the detective instead of describing the murder she called to report.

That phone call to the police (and the in-person interview that succeeds it) plays up another interesting thing that De Palma does in Sisters. In literature, an “unreliable narrator” is a viewpoint character whom the author has deliberately written so that his or her interpretations of the story’s action are not always trustworthy. What we have in Sisters is a cinematic equivalent to the unreliable narrator— call it an unreliable protagonist instead. When Grace describes the murder in Danielle’s apartment, what she tells the police does not square with what the camera shows us, and the more Kelly presses her, the further afield her version falls from the camera’s. At first, we merely wonder how Grace could identify Phillip as a “black male, about 25 years old” when all she can see of him from her window is his right hand and forearm as it scrawls “help” in blood on Danielle’s. By the time Kelly is in the room with her, Collier is saying that she saw Phillip stabbed, and can identify the killer as a woman meeting Danielle’s description. That’s impossible, though, because the stabbing happened in the living room, where there are no windows to the outside facing Collier’s apartment. De Palma refuses to comment on Grace’s exaggerations, leaving us alone to ponder what they mean for the rest of the film. The final irony is that she’ll still be lying about certain key facts by the end of the movie, but for a very different reason— regardless of whatever her earlier reasons had been.

The last act, though (the events of which will prevent Grace from ever speaking truthfully about her experiences), is the main thing stopping Sisters from being what it might look like on its face, and what De Palma’s reputation would certainly lead you to expect. The initial setup may suggest a snarky revision of Rear Window, and no one would greet such a film with much surprise given the director’s seemingly compulsive Hitchcock emulation in later years, but nothing I’ve seen or heard of in the Hitchcock oeuvre comes close to matching this film’s concluding delving into body horror and psychosexual dread. It’s the best part of the movie, and provides a compelling counterpoint to the muted but ever-present note of farce that underlies the first two thirds. As with Paul Bartel’s Private Parts, the last half-hour or so is the phase in which Sisters finally shows its teeth, and although there is humor even then, it serves to emphasize the horror of the proceedings rather than to lessen it. It also reveals De Palma as a much more agile filmmaker than he is often credited with being.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact