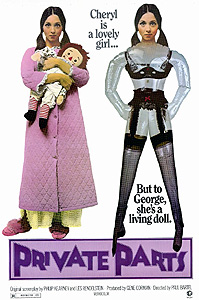

Private Parts/Blood Relations (1972) ***Ĺ

Private Parts/Blood Relations (1972) ***Ĺ

No, itís not the Howard Stern movie. Shame on you for even entertaining such a possibility. Rather, this is the film with which Paul Bartel, perhaps most visible as a member of Roger Cormanís stable of character actors in the 70ís and 80ís, first tried his hand at feature directing. Most of the movies Bartel directed subsequently were strange, subversive comedies (Death Race 2000, Eating Raoul, etc.), but Private Parts is something altogether differentó though no less subversive. His only horror film, Private Parts might usefully be thought of as Psycho reinterpreted in light of the urban decay and malaise of the early 1970ís. In many respects, it reminds me of something the young Frank Henenlotter might have made.

We begin with a time-honored cinematic tradition, a couple of small-town girls who have run away to the big city to find their fortune. It isnít going too well. Judy (Dear, Dead Delilahís Ann Gibbs) has managed to get herself a boyfriend at least, but to judge from the rather raggedy bedroom in which she and Mike (Len Travers) are having sex, an exciting and lucrative career has as yet eluded her. Meanwhile, Judy and her roommate, Cheryl (Ayn Ruymen), seem to be having some personality troubles. Guys treat Cheryl like a leper, and the closest thing she can get to any action in the bedroom is to spy on Judy and Mike. This time, Judy catches her, leading to a fight which ends with Cheryl packing up all her stuff and moving outó and taking Judyís wallet with her when she does.

As it happens, Cheryl has family in town, an aunt named Martha (Lucille Benson, of Halloween II and Duel) who owns the King Edward hotel. Donít let the name mislead you. Though itís possible that the King Edward was The Shit in its day, the place is now nothing more than a rapidly deteriorating flophouse, tenanted by all manner of wackos, eccentrics, bums, and losers. Even so, Martha initially refuses to rent Cheryl a room, on the theory that sheís an underage hooker, the one type of resident which she absolutely will not tolerate. Eventually, though, Cheryl convinces her aunt that they are indeed relatives, and that while she may be a shiftless parasite, Cheryl is no prostitute. Martha still insists that she wipe that skanky makeup off her face before she takes up residence in room 223, however. And honestly, thatís a pretty good call on Aunt Marthaís partó Iíve seen Parkinsonís patients do a better job of putting on lipstick and eye shadow.

Letís take a moment now to introduce the King Edward Weirdos. After Martha, who is plenty weird herself, what with her goofball mysticism and obsessive condemnation of female sexual expression, the first person Cheryl meets in the hotel is Mrs. Quigley (Dorothy Neumann, from The Terror and The Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow), a daffy old lady who thinks every young woman she sees is somebody named Alice. Then thereís the drunk who lives down the hall from Cheryl, whom nobody sees much except when heís on his way to or from the liquor store. The most colorful of the bunch is the leather queen priest up in room 337, who calls himself the Reverend Moon (Laurie Main)ó somehow I donít think the handle is just a coincidence. But for our purposes, the most important resident of the King Edward is George (Alien Loverís John Ventantonio), the reclusive photographer who lives in what I take to be the King Edwardís penthouse. Cheryl finds George attractive, but for some reason Martha is determined to keep the two of them apart.

A few hours after Cheryl moves into the King Edward, Mike stops by looking for her. Judy has sent him out to retrieve her stolen wallet, and at some point she remembered hearing that Cherylís aunt ran a hotel downtown. Martha is out at a friendís funeral when Mike arrives (she takes pictures of funerals because she hopes one day to capture on film the exact moment when the deceasedís spirit abandons the body), but the Reverend Moon tells him the girl heís looking for has just moved in. He also suggests that Mike should come up to his room a bit later, but thatís another matter. Mike never has to worry about talking his way past Moonís come-on, however, because the hunch that leads him down to the cellar in search of Cheryl brings him instead to somebody who chops off his head with an axe and then feeds his body into the hotel furnace.

Meanwhile, we are seeing that the attraction Cheryl feels toward George is fully reciprocated, but that the photographer has an extremely strange idea of courtship. There is an unoccupied room between Cherylís and the second-floor bathroom, which Martha uses as a storage space for all manner of junk, and George likes to hang out inside so as to spy on Cheryl in both bed and bathtub. He also takes to leaving things for the object of his affections to discover, depositing them on Cherylís bed while she is out of the room helping her aunt maintain the hotel. The first is an erotic manuscript (presumably his own composition), into which he inserts a note reading, ďHow do you like it so far, Cheryl?Ē at a key passage. Next, he gives her a slinky black negligee with a silver-glitter spider web pattern embroidered on it, again with a note. By this time, Cheryl has identified the source of these mysterious presents, and gotten wise to the underlying motivation as well. While you and I would probably greet Georgeís advances with nothing but horror, I suppose we have to make allowances for the fact that this is apparently the first time Cheryl has ever caught a manís eye. A freaky guy is still a guy, after all. The trouble is, Cheryl has no idea what a sick fuck George really is, or how much danger sheís getting herself into by flirting with him. Itís Judy who makes that discovery, when she comes looking for Cheryl and is led by Martha to the darkroom George has set up in the cellar. In that darkroom, Judy finds enlargements of photo-booth pictures of her and Cheryl, which George snagged from the latter girlís room. Something about these life-sized blowups feels decidedly sinister, and Judy has just enough time to start thinking about why when she is attacked and killed, just like her boyfriend. It seems safe enough at this point to conclude that George is the killer, and that Martha knows very well what heís up to. In fact, it will gradually become apparent that George is really Marthaís child, introducing a queasy current of incest to the already strong ďnothing good will come of thisĒ vibe that the developing relationship between him and Cheryl gives off. If Cheryl knew what was good for her, sheíd listen to her aunt, leave George alone, and give her romantic attention to Jeff (Stanley Livingston, from Bikini Drive-In and Attack of the 60-Foot Centerfold), the boy from the photo development shop down the street, who took a liking to her when she dropped off some film a few days ago. On the other hand, it seems that Jeff used to date that mysterious Alice whom Mrs. Quigley is always going on about, and because itís also looking increasingly like the vanished Alice was the last girl George took an interest in, too much time spent at the King Edward would probably prove fatal to Jeff, too. Itís also worth pointing out that the inflatable sex dolls which George likes to fill up with warm water and inject with his own blood donít begin to exhaust the warps, kinks, and distortions in Georgeís sexuality. Martha has given the photographer an upbringing that would win raised eyebrows even from old Mrs. Bates.

Someone who knew no more about Private Parts than what they could glean from the back of the video box might be tempted to dismiss it as nothing more than an early American experiment in the slasher genre, and move on to seemingly greener pastures. That would be a mistake. Though there is a slasher element to this movie, Private Parts gives the great bulk of its attention to setting up the head-on collision between the naÔve and relatively innocent Cheryl and the sexual monster which her aunt has created in the form of George. In fact, some commentators have gone so far as to call the slasher-style murders of Judy and Mike a gratuitous add-on, a mere bone tossed to the grindhouse horror audiences to keep them in their seats until Cheryl and George finally get together and the real action begins. Thereís something to that line of reasoning, too, as this film otherwise spends little time trying to meet the expectations of any generally recognized market segment. Really, Private Parts is a movie with no obvious natural audience, and it is a testament to the risk-taking spirit of the early 70ís that it was released at all, let alone by so weighty a studio as MGM. Gorehounds will probably want more bloodshed, the arthouse crowd which would most appreciate the movieís qualities as a character study will most likely be put off by its aura of filth and grime, and the sleaze factor will probably scare away most fans of dignified, old-fashioned horror films as well. That leaves Private Parts for the aficionados of true maverick cinema, and for us lovers of the weird, it is a treat indeed. Itís no exaggeration to say that Iíve seen no other movie quite like it, uniting as it does the study in evil in the same spirit as The Killing Kind or Maniac with the more traditional innocent-in-peril school. Like those later mind-of-a-killer movies, it gives us access to a great deal of the landscape inside Georgeís head (though, significantly, it also keeps from the audience the big secret which George is apparently keeping from himself), yet at the same time, it provides us with a more or less normal identification figure in Cheryl, and gives her enough attention to be taken seriously as a character. The result is a sort of double perspective which is almost unknown among horror films, in which we get to watch the deadly intersection of two lives from both points of view at once.

Another important point of distinction between Private Parts and the conventional serial killer movie is this filmís sardonic sense of humor, and it is here that Private Parts shows its kinship with Bartelís later work as a director. One can easily imagine the two snide and sarcastic policemen who are called in to pick up the pieces at the end showing up to perform the same function in Eating Raoul. The Reverend Moon would not have been out of place had he resurfaced in Death Race 2000. But what is most remarkable about the humor in this film is that it heightens the pervasive sense of unease rather than defusing itó who could Cheryl possibly turn to for protection with this Mad Hatterís tea party going on all around her? What we have here is not comic relief, but comic exacerbation. Itís too bad Bartel never made another horror movie, because his quirky, black wit meshes much better with the genre than the farcical antics with which most horror directors try to leaven the shocks, only to destroy them outright instead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact