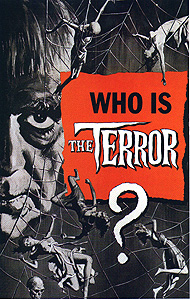

The Terror/The Castle of Terror/Lady of the Shadows (1963) *½

The Terror/The Castle of Terror/Lady of the Shadows (1963) *½

There have been many occasions over the years that I’ve been doing this (Pissing Jesus! Has it really been almost four?!) on which I’ve disdainfully described a movie as seeming to have been made without benefit of a script, as though the people responsible for it just made stuff up as they went along. Well today we're going to have a look at a flick that can be so described without the slightest exaggeration or hyperbole— Roger Corman’s The Terror really didn’t have a finished script when shooting began, and the details of the story were still being hammered out long after principal cinematography wrapped a scant two days later!

You want to know how a thing like that can happen? Okay, it’s like this... We all know what a skinflint Roger Corman is, and how eager he’s always been to get his movies made as fast (and thus cheaply) as humanly possible. In the case of The Raven, Corman raced so far ahead of schedule that he soon realized he’d have the picture wrapped up a couple of days early. He’d already paid for the studio time, though— to say nothing of the rather elaborate castle set that The Raven required— and the experience of making The Little Shop of Horrors had already taught him that two days was plenty of time for him to shoot a film. With that in mind, Corman offered The Raven’s cast and crew the chance to make a second picture’s worth of money for what seemed at the time to be only the most minimal additional time commitment, and a lot of them took the bait. The only problem with this scheme was that neither Corman nor any of his favorite screenwriters had a script already in hand that needed a castle, and there was no time to write one before the set was scheduled to come down. So in a fit of truly inspired audacity, Corman hired Leo Gordon (who had written The Wasp Woman for him back in the 50’s) to write him one a piece at a time, which he could then film scene by scene as Gordon delivered it to him. The result, of course, was that nobody but Gordon had even the vaguest sense of what the story was until shooting was almost completed, and even then, so many on-the-fly rewrites were carried out (all of which had to be at least superficially consistent with scenes already shot for the project to work) that it's no wonder it took Corman and four (four!) second-unit directors a total of nine months to create anything like a coherent movie out of what became The Terror.

Since The Terror was originally a spin-off from The Raven, it makes perfect sense that it would have much of the feel of a Corman Poe movie. That’s just about the only thing in this movie that does make sense, however. Lieutenant Andre Duvalier (Jack Nicholson, who happens also to be one of those second-unit directors I mentioned), an officer in Napoleon’s army, has been wandering for days around the German countryside, having been separated from his regiment in the aftermath of an especially hectic battle. It isn’t until he reaches the very shores of the Baltic Sea that Duvalier encounters another human being, and even then, it may be that he’s jumping to unwarranted conclusions. There’s a girl on the beach (Sandra Knight, from Frankenstein’s Daughter and Tower of London), and though she is extremely reticent and withdrawn, she seems friendly enough, leading Duvalier to drinkable water and eventually introducing herself as Helene. She has an odd habit of disappearing when the lieutenant turns his back, though, and does something even stranger after the two of them have had a little while in which to get to know each other. “Come with me— I want to show you something,” the girl says, and leads Andre back to the seashore. She then wades right out into the surf, straight toward a semi-submerged rock formation that channels the breakers into a series of ferocious liquid bludgeons. Understandably concerned for her safety, Andre splashes after her, but she has vanished by the time he reaches the treacherous stretch of water. Strangely enough, Duvalier is attacked at that very moment by a big, brown falcon which was nowhere to be seen a moment before. It’s almost as though the girl had transformed into the bird when the waves hit her.

And maybe that’s just what she did. Duvalier loses consciousness under the pounding of the waves, and when he comes to, he’s in a small cottage in the forest. The shanty’s apparent owner is an old woman named Katrina (Dorothy Neumann, of The Undead and The Ghost of Dragstrip Hollow), whose retarded, mute handyman Gustav (Jonathan Haze, from Teenage Caveman and The Little Shop of Horrors) rescued Andre from drowning. Katrina keeps a pet too, incidentally, and that pet is a strangely familiar falcon she calls “Helene.” She denies any knowledge of a girl living anywhere nearby, however. You don't buy that either, do you? Well Duvalier shares in your skepticism, especially when he is awakened that night by the falcon flying out the window and into the woods, and finds the human Helene hanging out in a clearing when he goes to pursue. Again, the messages the girl sends are decidedly mixed, for no sooner has she kissed him than she runs off and damn near leads him into a quicksand pit. Only a timely warning from Gustav (who is evidently not so mute as Katrina would like people to believe, and who looks to have been awakened in his turn by Andre’s noisy movements through the underbrush) saves Duvalier from sinking to certain death. Gustav also has a few interesting tidbits of information for Andre: the girl behaves the way she does because she is possessed, and the answers to all of the lieutenant’s questions may be found at the Castle Leppe. Andre puts about as much stock in Katrina’s protests that the castle is uninhabited as he does in her similar claims that her falcon is the only one answering to the name Helene in these parts.

Actually, by castle standards, the old place is pretty much derelict. Its owner, Baron Victor Frederick von Leppe (Boris Karloff), does still live there, but he does so accompanied only by a single manservant by the name of Stefan (Dick Miller, from The Premature Burial and War of the Satellites). And despite the baron’s obvious displeasure at having his solitude disturbed by a nosy young officer from France, he does open up enough to let it slip that he’s got some idea what Andre is talking about when he says he saw a girl skulking about on the castle grounds. Leppe leads Duvalier into the next room and shows him a portrait of a young woman who meets Helene’s description exactly. The catch is that said portrait was painted some twenty years ago— right before the girl it depicts died. Her name was Ilsa von Leppe, and despite the vast age discrepancy, she was the baron’s wife. Knowing now that something really weird is going on, Andre finagles a room for the night out of Leppe, and sets his mind to solving the mystery.

Rather than lead you through the search a piece at a time the way the movie does, I’m just going to drop it all on you in a heap. After all, it’s not like I’ll be ruining much by giving away the secrets of such a dismal little film. Baron von Leppe hasn’t been entirely honest with his guest. Ilsa was indeed his wife— his second one, in fact, raised from the peasantry when her seigneur found in her a cure for his grief at the death of his first. And Ilsa did indeed die twenty years ago, but what Leppe has tried to keep to himself is that the girl died by his own hand. He had been called off to military service, and when he returned a year later, he found her in bed with a man named Eric— Katrina the woodswoman’s son— and went quite berserk. Eric escaped from Leppe’s wrath, but it did him little good; Stefan shot him dead in a struggle to prevent his flight from the castle. Now, or so the baron believes, the spirit of Ilsa has begun visiting him to express her forgiveness of his rash actions, and to reveal to him a way by which they may be reunited. What Leppe doesn’t realize is that Ilsa’s spirit has (I think) been channeled by Katrina into the body of another peasant girl— the mysterious Helene— because the ghost’s true purpose dovetails nicely with the witch’s own. It’s not forgiveness Ilsa has on her mind, but vengeance, and as the mother of the girl’s murdered lover, Katrina figures that vengeance suits her just fine, too. The plan is for Ilsa/Helene to con Leppe into killing himself, incurring thereby eternal damnation for his soul. What neither conspirator has reckoned on is Andre’s inexplicable love for Helene, which gives him plenty of incentive to try to separate the malevolent spirit from her body. And what nobody has reckoned on is that Baron von Leppe isn’t really Baron von Leppe at all, but rather the missing Eric, who turns out to have murdered the baron and then gone so mad with remorse that he literally absorbed his victim’s personality. That means Katrina’s clever scheme will really achieve the precise opposite of the revenge she desires. It all ends (and how could it be any other way?) with the destruction of the castle— but by this time, even Corman had started to feel uncomfortably like he was repeating himself, and that destruction comes in a flood rather than a fire.

All things considered, The Terror turned out much better than it had any right to, which is to say that it’s not totally unwatchable. By this point in their respective careers, Corman and Karloff could do this sort of thing in their sleep, and their unshakable self-assurance goes some way toward making up for the movie’s almost innumerable faults. They can’t disguise the complete lack of a pre-planned story, however, nor paper over the fact that none of the pieces of what eventually came to pass for The Terror’s script quite fit together. The “climactic” revelation of Karloff’s true identity is completely pointless, adding nothing of value to the tale that leads up to it and adding a number of logical difficulties to a plotline that already had more than it could support. The true nature of Ilsa/Helene is never fully explained, and what hints are dropped by the time “The End” appears on the screen are so flatly contradictory that no sense could possibly be made of them. There’s far too much recycling going on, both of “plot” points and of visual cues, and attentive viewers will have much more fun trying to figure out which previous Corman Poe opus the various props, sets, and matte paintings originally appeared in than they will from just watching the movie. And to cap it all off, Jack Nicholson shows that he simply was not ready to take on a leading role at this early stage of his career. He had been excellent in his supporting role in The Raven, but his turn here on center stage makes even Nick Adams’s somnolent performance in the subsequent, similar Die, Monster, Die! look good. The knowledge that it was made without a real screenplay confers a certain perverse fascination upon The Terror, but while failing so signally to be good, it never quite sinks to such depths of craptitude as to become enjoyable for its shortcomings.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact