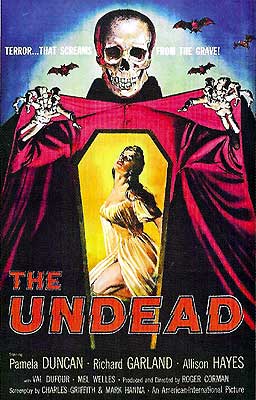

The Undead (1957) ***½

The Undead (1957) ***½

You know what? Fuck it. Since I’m already reviewing The Bride and the Beast for this update, let’s cue up The Undead, too, and make it a double feature. The theme? Bridey Murphy Goes to the Drive-In!

The Search for Bridey Murphy falls a bit outside the purview of this site as I currently understand it, but it’s been surprisingly influential for a film (and previously a book) that’s fallen so far out of pop-culture visibility. The story of that influence began inauspiciously enough, on an evening in 1950 when a previously undistinguished Coloradan named Morey Bernstein saw hypnosis demonstrated as a party trick, and became fascinated with the phenomenon. Over the next two years, Bernstein taught himself to put people under, and to hear him tell it, he became an amateur hypnotherapist of some ability. By 1952, he was experimenting with hypnotic regression, and while plying the technique on an acquaintance by the name of Virginia Tighe, he got it into his head to try sending her back to a time before her birth. I gather that Bernstein was searching for buried memories of life in the womb, but what he apparently got was something even stranger. Upon reaching the desired depth of regression, Tighe began exhibiting an entirely different personality, who spoke with a pronounced Irish accent, and called herself “Bridey Murphy.” This second self claimed to have been born in Cork in 1798, and to have died in 1864 of injuries sustained in a fall. Over numerous subsequent sessions, Bernstein teased out a great deal more information about this apparent previous incarnation of Tighe’s, until eventually he’d collected enough material to interest a reporter from the Denver Post. The paper ran a series of articles on the strange affair throughout 1954.

Bernstein retold the story himself in book form two years later, and so big a stir did the pre-publication announcement cause that his agent was able to sell film rights to Paramount before The Search for Bridey Murphy even appeared in bookstores. That title proved ironic, because a small army of curious journalists would subsequently reveal that searching for Bridey Murphy was precisely the thing that Bernstein never bothered to do. Barely any of the details that Tighe had revealed about Murphy’s supposed history stood up to even the most rudimentary fact-checking: there were no birth, marriage or death records in the appropriate times or places, no grave on the grounds of the church where she was said to be interred— and the church in question wasn’t even built until 1921, anyway! More interestingly, though, quite a few other elements Murphy’s ostensible biography lined up with events or figures from Tighe’s own earliest childhood, a period of which she claimed to have no conscious memories. So although The Search for Bridey Murphy was a bust as a case study in reincarnation, it sheds considerable light on the phenomenon of cryptomnesia and the interaction between hypnotic suggestion and the subconscious mind.

Nevertheless, popular fascination with the Bridey Murphy story, and with the concept of past-life regression more generally, persisted for years. The concept was just too much fun to play around with, even for people who didn’t actually believe in it. My personal favorite manifestation of late-50’s Brideymania was the vogue for “come as you were” parties, to which attendees would show up dressed as people whom they fancied they’d been in previous incarnations, but of course what we’re really here to talk about is how Hollywood’s less reputable operators rode the same wave. American International Pictures made at least two bids to cash in on the strangely resilient fad, entrusting them to some of the studio’s most prolific directors, but the trash auteurs in question weren’t content to limit the premises of these movies to mere reincarnation. As we already discussed long, long ago, Edward Cahn’s The She-Creature used the Bridey Murphy case as the jumping-off point for a loopy monster rampage, asking what might come of regressing someone into an identity from half a billion years before the emergence of the human species. Roger Corman’s The Undead is a lot more conventional than that, but it treats its subject matter more thoughtfully, intelligently, and even creatively, once you look past the absence of attention-getting lunacy like torpedo-tittied lobster girls called forth from the depths of time. It might even be Corman’s single best movie of the 1950’s.

Quintus Ratcliff (Val Dufour) has just hired a whore. But instead of taking the surely pseudonymous Diana Love (Pamela Duncan, from Attack of the Crab Monsters) to either his home or a cheap motel, he brings her to the Institute for Psychic Research— specifically to the on-campus residence of Professor Ulbrecht Olinger (Maurice Manson, of The Creature Walks Among Us). That’s because Ratcliff wants Olinger to witness an ethically dubious experiment, meant to prove the validity of the “crackpot” ideas that got the younger man hounded out of the institute some years ago. Ratcliff, you see, is a sort of scientific mystic. Not only is he a believer in the power of hypnosis to grant access to the memories of our previous incarnations, but he also contends that a hypnotized consciousness can reach across time to communicate directly with its former selves— and even that is only the beginning, if the techniques that Quintus studied in a Tibetan monastery are all they’re cracked up to be. What Ratcliff now proposes is to put the lamas’ ancient teachings to the test. He will send Diana into the deepest possible hypnotic trance, and hold her there for fully 48 hours while she goes reconnoitering through all her former lifetimes in search of an incarnation sufficiently well attuned to her current self for her to merge with it temporarily and direct its actions from across the ages. Olinger wants nothing to do with it, but acquiesces once Ratcliff makes it clear that his participation is the only way to ensure the woman’s safety. As for Diana herself, well… This probably isn’t the kinkiest thing a man’s ever tried to pay her to do, you know?

Diana Love’s Bridey Murphy turns out to be a woman of the unspecified European long-ago, called Helene. Soon after contact between Diana and Helene is established, the temporal focus shifts to the latter’s era, where she finds herself unjustly condemned for witchcraft. Diana, being considerably grittier and more streetwise than her previous self, easily guides Helene in outwitting and neutralizing her jailer (The Raven’s Aaron Saxon), permitting her escape from the keep where she’d been locked up to await her date with the headsman the following dawn. Now if Helene could afford to hang around in the vicinity of the tower, she’d have shortly enjoyed a reunion with her lover, Pendragon (Richard Garland, from Son of Ali Baba and Panic in Year Zero!), who is even then on his way to assess the prospects of rescuing her. Her circumstances demand a more proactive approach, however, for not only could the jailer recover at any time, but the area is under patrol by a knight (Don Garrett) whom the accused witch will find far more formidable, even with Diana calling the shots for her from inside her mind. Helene completes her escape by hitching a ride inside the coffin that crazy old Smolkin the gravedigger (Mel Welles, of She Beast and The Little Shop of Horrors) is on his way from the nearest village to bury.

There’s some irony in that, because Smolkin is the very man whom Helene was accused of bewitching. Nevertheless, he bears the supposed sorceress no grudge— for if he’s mad, then surely his own memories are untrustworthy, and he has no reason to believe anything that he recalls being said or done at her trial. When Smolkin hears Helene hammering for release from the coffin as soon as the coast seems clear, he not only doesn’t hand her over to the aforementioned patrolling knight, but even gives her directions to the best imaginable safehouse for accused witches. That would be the cottage of Meg Maud (Dorothy Neumann, from 13 Frightened Girls and Private Parts), a witch so clever that she cheated the Devil out of her own soul when the time came to hand it over. Meg’s a kind sort, though, and once she satisfies herself that Helene really isn’t a witch, she undertakes to do everything in her considerable power to keep the girl safe from the headsman until past sunup. You see, the law in these parts stipulates that servants of Satan must be executed at the crack of dawn following the night of the Witches’ Sabbath— which is tonight— so if Helene can stay out of trouble until then, she’s in the clear for a whole ’nother year. It should further go without saying that Pendragon has already vowed to spend that year exonerating her.

But if Helene truly is innocent, then who cast the spell depriving poor Smolkin of his wits? Meet Livia (Allison Hayes, from The Disembodied and The Zombies of Mora Tau), a conjuror comparable to Meg Maud in power, but not half so scrupulous. Livia covets Pendragon, and she’s convinced that he’d be hers for the asking if Helene were out of the picture. Thus the frame-up over Smolkin, and thus also the evil witch’s determination to see Helene back in the dungeon before sunrise. Livia will trick Helene into the waiting arms of the authorities if she can. She’ll use magic against her, too, if Meg Maud will but allow her an opening— be it her own magic or that of the imp (Billy Barty, of Demon, Demon and Willow) assigned to her by the Prince of Darkness. And if all else fails, Livia is fully prepared to turn Pendragon’s love for Helene against her. After all, the power of Satan (Richard Devon, from War of the Satellites and The Seventh Sign) would certainly suffice to free the unfortunate girl from her fix, and Old Scratch is always open to purchasing new souls during his appearances at the Witches’ Sabbath. Livia cannily reckons that Pendragon, if pushed hard enough, will deem even damnation an acceptable price to pay for Helene’s safety, and that in the long run, his payment of such a price will mortally wound the couple’s relationship in one way or another. A woman with black magic at her disposal can afford to take an awfully long view of “the long run,” too.

Meanwhile, back in the 20th century, a new and altogether more complicated factor in the age-old drama has come to light. Through the kinds of channels that one gains access to when one learns past-life regression from Tibetan monks, Ratcliff discerns that Diana’s intervention into Helene’s life is on track to alter the timeline irrevocably. From the standpoint of 1957, Helene’s execution was an accomplished fact. By throwing it into question from the standpoint of Once Upon a Time, Diana has opened the door to a new course of history in which neither she nor any of her past or future selves subsequent to Helene will ever be able to exist. Despite his general lack of principles, that’s a far more serious bad outcome to his experiment than Ratcliff is willing to countenance. Fortunately, those monks taught him one more trick with which he might salvage the situation even yet. So long as Diana remains both entranced and in contact with Helene’s consciousness, Ratcliff can hypnotize himself into a state capable of riding that connection from his own time to Helene’s. And once there, he can project an astral body in which to undo what Diana, Helene, Pendragon, Meg Maud, and a helpful innkeeper called Scroop (Bruno Ve Sota, from Creature of the Walking Dead and Hell’s Angels on Wheels) are in the process of doing to history. Watching that contest play out is going to make for the most entertaining night the Devil has spent on the material plane in centuries.

Very few Hollywood movies have made smarter, more effective use of ridiculously limited resources than The Undead. Upon close examination, the film resolves itself into little more than several small groups of characters repeatedly racing back and forth among the same three locations (the dungeon tower, Meg Maud’s cottage, and Scroop’s inn) by traversing a fourth (the woods surrounding all of the above). What’s more, all of those places had to be built on a five-figure late-50’s AIP budget, on a soundstage converted hastily from a department store that had gone out of business not long before. The whole affair should look cheap and shoddy, but instead it takes on a Val Lewton-ish dreamlike quality, which dovetails perfectly with the conceit that we’re watching events of the distant past through the subconscious perception of a woman in deep hypnosis.

That dreaminess is heightened further by the slipperiness of when and where Helene is supposed to have lived. Cannily, The Undead never offers a date more solid than “the second year of the reign of King Mark,” and never specifies a country at all. The King Mark that springs immediately to my mind, however, is the one who supposedly ruled Cornwall sometime during the 6th century— the one who figures in the Arthurian Cycle as the husband whom Isolde cuckolds in her affair with Sir Tristan. That would place Helene very early in the Dark Ages, but the sets and costumes are designed instead to suggest in various ways every century from the 12th to the 14th. That’s plausibly Arthurian in a different way, though, because it was precisely during those latter centuries that the stories, songs, and epic poems comprising the Matter of Britain were largely written. On the other hand, the heyday of witch trials was later still, spanning the mid-15th century through the late 17th. History in The Undead thus collapses to form a sort of composite mythic past, of exactly the sort that one encounters in the literature of any of the eras that we might posit as Helene’s “true” time. Consider Hamlet, for example, which presents an 8th-century Denmark culturally and politically indistinguishable from England 800 years later, seemingly peopled by members of every nation in Europe except the Danes.

It isn’t just to be snide that I draw a connection between The Undead and Shakespeare, either. Another of this movie’s remarkable traits is the extremely convincing counterfeit of blank verse that writers Charles B. Griffith and Mark Hanna used for the dialogue in the Olden Days sequences. As someone who quickly and easily becomes exasperated by modern writers’ frequently fumbling attempts to render outmoded manners of speech, I often found myself wanting to stand up and applaud Griffith and Hanna’s efforts here. What might be even more impressive, though, is the cast’s success in consistently sounding like they mean it when the script gives them mouthfuls like, “I know not— some torture that my brain doth conceal from me! Nor may I speak his name. But this much I do know: be he man or monster, demon or saint, his heart doth hunger for the death of me.” Allison Hayes is the clear MVP in that department, rattling this stuff off like it’s the way she naturally talks, and giving it a depth of feeling that many B-movie performers of the 1950’s struggled to achieve with dialogue that really should have come naturally to them.

But the biggest surprise in The Undead may simply be how hard it commits to what could easily have been a throwaway premise, teasing out all sorts of thought-provoking angles, and hiding even more for the viewer to find. The metaphysics get particularly interesting when it comes out that Helene’s escape from the headsman has put all of her subsequent incarnations in jeopardy. Not only does that lead to such extraordinary turns of events as Quintus traveling back in time to meet Satan face to face, or Helene taking a psychic straw poll of her future selves regarding whether they consider their lives worth living, but it also sets up an even darker reading of the accused witch’s future than the script ever openly puts forward. Think for a bit about why Helene making her getaway from the chopping block in that life might foreclose her from having any future incarnations. Think about what reincarnation of the sort posited here would mean for the nature of the soul. And think about what would have to happen at next year’s Witches’ Sabbath for Helene’s soul to get pulled out of play in the eras to come. The overt twist ending is pretty great too, mind you, but it’s this sotto voce hint of still grimmer tragedies waiting in the wings that gives The Undead’s final act its bite.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact