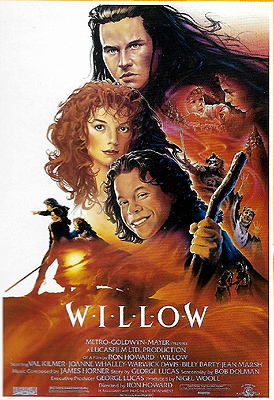

Willow (1988) **½

Willow (1988) **½

In much the same way as the Star Wars saga was George Lucas’s Flash Gordon, Willow was his Lord of the Rings. The two properties had their genesis at about the same time, too, for the earliest recognizable version of the story that became Willow dates all the way back to 1972. There was an important difference between the developmental track of Star Wars and that of Willow, however, which largely comes down to a matter of timing. The former movie, derivative though it was, was nevertheless out in front of the zeitgeist. So many years had passed since anything with its sensibilities had been seen on theater screens that the “everything old is new again” principle came into play, and the material aspects of the production raised the bar so high that they legitimately did constitute something previously unseen in terms of miniature and optical effects, monster makeup, and prop design. Star Wars was a cinematic watershed, and other, even more mercenary filmmakers would devote themselves to ripping it off repeatedly for years to come. Willow, on the other hand, appeared when the resurgence of fantasy movies initiated by Excalibur, Dragonslayer, and Clash of the Titans (and boosted into orbit by Conan the Barbarian) was long past its apogee. It lacked even the illusory freshness of revival after a long period of dormancy, so that every one of its innumerable cribs from antecessors both recent and antique was glaringly obvious. Audiences had both been here and done this by 1988, and Willow’s eight-figure production cost hadn’t bought all that noticeable an improvement over Legend, Labyrinth, or even Krull. In the end, this movie’s principal legacy was to finish convincing the major studios that there was no more money to be made in genre fantasy, and while that wasn’t entirely fair either to this movie or to fantasy films as a whole, it wasn’t entirely indefensible, either.

There is, inevitably, an opening crawl, in which we are made acquainted (also inevitably) with a Chosen One prophecy and a villainous ruler’s plans to counteract its fulfillment. The wicked sorceress-queen Maleficent… no, wait— Bavmorda (Jean Marsh, from The Changeling and Unearthly Stranger)— has learned from her staff of soothsayers that a girl is about to be born who is destined to overthrow her. You’ll never guess what Bavmorda’s response to that news is— unless, I suppose, you’ve seen any fantasy movie since Jason and the Argonauts, or even just read the Gospel According to Matthew. That’s right, Bavmorda takes it upon herself to kill her foretold usurper in infancy, to which end she has her soldiers round up every pregnant woman in the realm for incarceration in her castle dungeon. Then the fortune-tellers can examine each baby as it is born for one of the morphologically improbable birthmarks that always seem to go along with prophecies of this sort. As soon as the right kid comes to light, Bavmorda will not only kill her, but subject her as well to a ritual that will banish her spirit to a dimension from which it can neither reincarnate itself nor exert any influence at all upon the mortal plane. This scheme pans out exactly as well as it did in The Beastmaster (or in the Bible, for that matter), for the mother of the prophesied deliverer manages to smuggle her child out of the dungeon in the hands of a compassionate cleaning lady. (Moral of the story: just let the damn prisoners languish in their own filth like a Borgia would have.) Bavmorda sics a pair of the Killer Shrews that she uses as bloodhounds on the disloyal servant once she figures out what has happened, but it’s a bit late for that. By the time the shrews catch up to their quarry, she’s set the baby in a watertight basket, and floated her off to whatever safety there may be for her down the river.

Baby Jesmoscules eventually washes up in the Shire (or at any rate, its Route 66 roadside attraction equivalent), where she is discovered by a pair of Hobbit— er, Nelwyn— children. Their father, Bilbo Baggins— I mean, Willow Ulfgood (Warwick Davis, from Leprechaun and Return of the Jedi)— recognizes her at once as a Daikini (that is, human) infant, and is adamant that no one in his household is going to adopt the tiny giant. Willow has plenty to worry about already between Mr. Burglekutt (Hardware’s Mark Northover), the richest man in the village, attempting to lever the Ulfgood farm out from under him with an unpaid debt, and the pressures of his own efforts to earn an apprenticeship in magic under the High Aldwin (Billy Barty, of Legend and The Undead). However, the moment his wife, Kiaya (June Peters), sees the kid, it looks like Willow might as well just resign himself to a supporting part in an all-dwarf high-fantasy version of Mighty Joe Young, with Kiaya as Jill Young and Baby Jesmoscules as the gorilla. Meanwhile, the long-suffering farmer is running behind on the spring planting (meaning that he’s also running behind on acquiring the means to pay back Burglekutt), and he ends up flunking the High Aldwin’s entrance exam for apprentices.

That’s about where matters stand when the Killer Shrew shows up. Far from giving up on her prophecy-thwarting efforts, Bavmorda has brought out the big guns, dispatching both her daughter, Sorsha (Joanne Whalley), and her military commander, General Kael (Pat Roach, of Kull the Conqueror and Conan the Destroyer), to scour the land for the missing baby— the former in defiance of the soothsayers’ advice that Sorsha is fated to betray her mother. No, I don’t understand the point of employing seers if you’re not going to listen to them, either. Be that as it may, it would appear that the hounds have picked up the scent at last, and although Vohnkar (Phil Fondacaro, from Troll and Bordello of Blood), the best fighter among the Nelwyns, succeeds in killing the beast, Burglekutt is not wrong in asserting that there are surely more where it came from. At an emergency meeting of the village council, Willow has no choice but to admit that he and his family have been looking after a Daikini foundling, and the High Aldwin’s prescription is that someone must carry the child out of the Pseudo-Shire to the Daikini Crossroads, there to palm her off on the first Daikini to pass by. Burglekutt “magnanimously” nominates Willow for this “honor” (his real motivation, of course, is to further delay Willow’s planting in the hope of hastening the day when he can foreclose on the outstanding loan), but the seriousness of the situation quickly turns the trip to the Daikini Crossroads into a rather large production. When Willow sets off, he does so accompanied by his friend, Meegosh (David Steinberg), a party of warriors under Vohnkar’s direction, and even Burglekutt in a veritable Fellowship of the Teething Ring. The High Aldwin makes his own contribution, too, in the form of a handful of acorns which he claims will turn anything they’re thrown at to stone.

As it happens, the first Daikini the travelers see is in no position to adopt anybody. The crossroads doubles as a place of public execution, where criminals are set out in cages to die of thirst, hunger, or exposure as an object lesson to the populace. Inside one of those cages right now is a miscreant by the name of Han Solo— or rather, Madmartigan (Val Kilmer, from Red Planet and The Island of Dr. Moreau)— although exactly what he did to earn his fate apparently got left on the cutting room floor. Madmartigan sensibly tries to parley with the Nelwyns anyway, offering to take custody of the baby in exchange for them letting him out of the cage, but at first only Burglekutt (who plainly doesn’t give a shit what happens to the kid, so long as she stops being the Nelwyns’ problem) has any inclination to cut a deal. It’s a crossroads, after all— surely somebody more suitable than a condemned criminal is bound to come along eventually? But the several thousand somebodies who come along a short while later aren’t looking to become foster parents, either. These men are an army bound for Galladorn, which they mean to defend from attack by Bavmorda’s forces, and their leader, Airk (Gavan O’Herlihy, of Prince Valiant and The Descent, Part 2), wants nothing to do with Nelwyns, or babies, or least of all Madmartigan. Eventually, Burglekutt convinces the others that Madmartigan will simply have to do, and the Nelwyns set off for home after springing the Daikini from his confinement. Not that Willow actually likes the idea, mind you.

He likes it even less a short while later, when a Brownie riding a hawk (Kevin Pollack, from End of Days) flies overhead, crowing about stealing a baby from a stupid Daikini. Willow and Meegosh take off in pursuit of the miniscule kidnapper, but all it gets them is the Gulliver treatment from a whole army of Brownies. Things aren’t as bad as they seem, however. The Brownies work for Galadriel— sorry, Cherlindrea (Maria Holvoe)— a fairy princess who knows Baby Jesmoscules’s true identity (turns out her real name is Elora Danan), and who wants to see to it that she lives to fulfill her destiny. To that end, Cherlindrea hands Willow her magic wand, with instructions to bring both it and Elora Danan to an island in a lake somewhere, so that they may be placed in the protective custody of the good witch Glinda— no, Fin Raziel (eventually to be played by Patricia Hayes, from Candles at Nine and The Neverending Story). And so begins the Hero’s Quest in earnest, with the baby-snatching Brownie and another of his kind (Rick Overton, of Eight Legged Freaks) guiding Willow on the way to Fin Raziel’s island, while Meegosh returns home to tell the rest of the Ulfgood family what’s up.

That quest leads first to a Daikini village that certainly isn’t Bree, where Willow is reunited (much to his disgust) with Madmartigan at an inn that certainly isn’t the Prancing Pony, and where Sorsha and her troops reveal themselves to be sorry substitutes for the Black Riders; Madmartigan, incidentally, demonstrates that he’s Indiana Jones as well as Han Solo while fighting his and the little people’s way past Sorsha’s men. The arrival at the island obviously comes much too soon not to have serious strings attached, and sure enough, we see that Fin Raziel and Bavmorda have already met. The good sorceress got the worst of that encounter, and was transformed into a… What the hell is that thing, anyway? A lemur? A honey glider? Anyway, Willow will have to use Cherlindrea’s wand to change Fin Raziel back, so it’s rather unfortunate that he didn’t get that apprenticeship he wanted. The poor lad totally sucks at spell-casting, and spends the whole time between here and the climax turning Fin Raziel into just about everything but her true human self. Madmartigan next adds Lando Calrisian to his list of Lucasian doppelgangers by selling out Willow, the prosimian witch, and Elora Danan, but quickly discovering that he’s fucked himself over, too, in the process. A mishap with some Brownie enchantment powder during the subsequent escape causes Madmartigan to fall in love with Sorsha, providing her with an incredibly lazy excuse to turn on Bavmorda as foretold. Tir Asleen, the stronghold that Fin Raziel keeps going on about as a safe haven for the baby, turns out to be less Minas Tirith than Khazad Dûm, so that Willow and Madmartigan find themselves caught between General Kael on one side, and a pack of trolls and a two-headed blob-dragon on the other. And our heroes eventually fall in with what’s left of Airk’s Rebel Alliance after their catastrophic rout at Galladorn, furnishing them with an army to lead against Bavmorda’s castle at Pedro’s South of the Mordor. Cue big sorceress smackdown and an equally big round of happily-ever-afters.

I want you all to notice something here, which I know I missed completely when I saw Willow during its theatrical run. This whole story is set in motion by a prophecy foretelling that Elora Danan will overthrow Queen Bavmorda, bringing an end to the hegemony of evil over Peripheral Earth. That’s not what happens, though— not at all. When Bavmorda’s downfall comes, Elora Danan is incapable of doing much of anything beyond filling up her diaper, and the wicked sorceress meets her end in a clash of conjuring against Fin Raziel and Willow. The prophecy, in other words, is not merely misleading (which is the oldest of old hats), but flat-out fucking wrong. I would love to think that this was deliberate, because the one thing I can’t remember seeing in any me-too sword-and-sorcery movie of the 80’s is a conscious taking-up of Conan the Barbarian’s implication that magic isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Sadly, though, I really don’t believe that’s the case here. The queen’s fortune tellers are right on the money about Sorsha, after all. The High Aldwin, for all his apparent doddering and buffoonery, isn’t fucking around about those enchanted acorns. If Fin Raziel is far less powerful than she believes, she’s also about 60 years older than she realizes, and way out of practice. And Bavmorda has only to tell Airk’s army that they’re all pigs for it to become literally true. So no. Magic in Willow works. It’s just the prophecy that motivates the entire plot that comes up short— and without anyone involved seeming to notice, at that! I don’t think I’ve seen a movie so completely lose track of its premise at the conclusion since Jason and the Argonauts. I suppose that’s sort of appropriate, in an annoying way.

Something else I missed back in 1988 is how strange Willow is, tonally speaking. Its subject matter is generally in line with the fantasy epics of the 50’s and 60’s, but its attitude, so to speak, lurches erratically between the “all ages” sensibility of those films and a more overtly juvenile approach that rather reminds me of Labyrinth. The movie can’t seem to make up its mind whether the characters are in any real peril from one scene to the next; one moment, Madmartigan is hacking his way through Kael’s soldiers with a stolen broadsword, and the next, Willow and Elora Danan are tobogganing down a craggy mountainside on a discarded shield like they’re in an episode of the old Saturday morning “Dungeons & Dragons” cartoon. Willow’s Brownie guides, meanwhile, are comic relief of a particularly crude and childish sort, their antics obviously designed deliberately to deflate the mood whenever the film finds itself in danger of generating a moment of actual tension. And I cannot for the life of me understand why they speak with exaggerated French-Canadian accents, like David Foley and Kevin McDonald making fun of the Quebecois.

Don’t let me mislead you, though; the truth is that I’m rather more favorably disposed toward Willow than all the foregoing would suggest. It isn’t a bad movie so much as a frustratingly lazy one, with no discernable ambitions beyond those that can be realized by writing an enormous check to a set fabricator or a visual effects firm. But on that level, at least, it’s mostly a very successful film (I say “mostly” because the Tir Asleen trolls are nothing but guys in terrible ape-man suits, looking more like something out of Ironmaster than the work of Industrial Light and Magic), and I can easily see why my fourteen-year-old self left the theater without any major complaints. Although the world of the film is a far cry from the fascinatingly weird early concept art by Jean “Moebius” Giraud, it is nevertheless a perfectly serviceable ersatz Middle Earth. (I’m not at all sure that sticking with Moebius’s Japanese-inflected designs would have made Willow a better movie, but it certainly would have made it unique at the time.) The digital morphing effects used for Fin Raziel’s repeated transformations— a technology that was actually invented for this movie— are deployed in a much less obtrusive manner than one usually sees with the debut of a special effects technique, which might make this the last time we ever saw subtlety of any kind from George Lucas. Madmartigan’s fight against the stop-motion blob-dragon is a major highlight, with good choreography and considerable imagination on display in both the monster’s design and the means whereby it is eventually defeated. I’m at a loss to point out more than a single creative risk taken by Willow, but as timid, by-the-numbers genre fare goes, this is more than acceptable.

There is indeed one chance being taken here, though, and it would be remiss of me to wrap up this review without drawing just a bit of attention to it. On the surface, it’s no big deal, but its significance is actually kind of huge: Willow is one of the very few movies I’ve seen in which little people truly are presented simply as little people. Paradoxically, Willow’s status as fantasy, and the title character’s status as a sort of magical parahuman, are probably the very things that made such treatment possible. In 1988, it would have been prohibitively expensive to cast actors of full adult stature as the Nelwyns, and to employ special effects trickery to shrink them down to Hobbit size. The digital editing software that enabled Peter Jackson to make Elijah Wood, Sean Astin, and John Rhys-Davies look half their true height didn’t yet exist, and with all the other stuff already on the effects people’s to-do list, it would rapidly have become an insupportable hardship to use forced perspective and/or bluescreen matting in every frame featuring the title character or one of his compatriots. (Finding an appropriately enormous baby to represent Elora Danan in the medium and long shots would have been no picnic, either.) Hiring folks who really were Hobbit-sized was the only practical option, just as it had been in 1939, when MGM signed up a whole village’s worth of dwarves for The Wizard of Oz. There’s a big difference between Willow’s Nelwyns and that movie’s Munchkins, though. The Nelwyns are not defined by cuteness. Nor are they human oddities like the sideshow little people of Freaks, or living sight gags like the cast of The Terror of Tiny Town. Willow himself is the hero of this picture, and his third-place credits billing notwithstanding, Warwick Davis is unmistakably its star. Note, too, that there’s no sociopolitical piousness or self-congratulation over that fact anywhere to be seen. Nobody, either behind the camera or in front of it, regards Davis or his character as a dwarf, because for the purposes of the movie, he isn’t a dwarf; he’s a Nelwyn, and it’s completely normal for Nelwyns to be three feet tall and squatly proportioned. Willow was by no means the first movie to offer a little person such a role, of course, but it was surely among the first to do so while striving so hard for blockbuster status, and coming so close to attaining it. Disappointed as Willow’s distributors were in its performance, it was the top-grossing film in the country during its opening weekend, and its profitability worldwide was certainly comfortable enough. Between its wide exposure and its respectful attitude, Willow might have done more to enhance the dignity of midgets and dwarves than any other single film yet made.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable devoted to movies in which little people play big roles. Click the banner below to read the rest of the Cabal’s contributions.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact