Ironmaster / La Guerra del Ferro (1983) -**½

Ironmaster / La Guerra del Ferro (1983) -**½

You might expect that between The Man from Deep River, The Emerald Jungle, and Make Them Die Slowly, Umberto Lenzi would have said everything he had to say about stone-age primitives. However, in each of the aforementioned films, the primitives in question had been living in a very localized stone age, and the central premise concerned a culture clash between them and various representatives of the modern world. Obviously, a movie set in a time when flint core tools were the height of modernity would be a very different proposition. Furthermore, and of considerably greater importance, no sooner did Lenzi finish the last of his cannibal movies than French director Jean-Jacques Annaud attracted a truly astonishing amount of attention with Quest for Fire. Annaud’s film was uncharacteristically serious for a caveman picture, and it garnered enviable amounts of both money and critical praise all over Western Europe and North America. Frankly, it’s rather amazing that Lenzi let an entire year go by without ripping it off. Rip it off he did, however, for in 1983, Lenzi weighed in at last with Ironmaster.

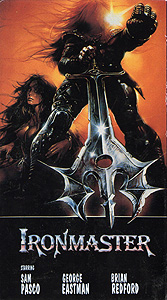

Wait— Ironmaster?! A movie set in the stone age is called Ironmaster?!?! Yes. And we are indeed talking about the same Ironmaster whose sun-faded box you remember seeing at your local mom-and-pop video rental shop back in VHS days, the one with the cover art more appropriate to a Conan cash-in, or better yet, a Man-o-War album. You see, in Latin Europe, Quest for Fire was called The War of Fire instead— La Guerre du Feu in France, La Guerra del Fuoco in Italy. Lenzi called his film The War of Iron, and the phonetic resemblance between La Guerra del Fuoco and La Guerra del Ferro is such that anybody familiar with the Annaud movie would have caught the reference immediately. Not so much in the English-speaking world, especially when you factor in that blatantly misleading cover painting. Indeed, I’m inclined to blame the box art for the intense loathing that Ironmaster tends to inspire, for if you watch it expecting a cheap barbarian flick (which is what you obviously would expect), you’re probably going to be pretty pissed off by the end. Certainly that’s how I reacted on both of the occasions when I fell for a similar ploy, first when I rented Knives of the Avenger under the title Bladestorm, then again when I rented The Arena under the title Naked Warriors. Far be it from me to suggest that Ironmaster is any good, but neither is it bad enough on its own merits to earn such enmity from people who weren’t hoodwinked into thinking they were getting something like Deathstalker or The Beastmaster.

The Ironmaster of the title is a hunter named Vuud (George Eastman, from The Grim Reaper and Warriors of the Wasteland), but when we first meet him, he’s merely one of several Stickmasters. Specifically, he’s an accomplished hunter among a band of paleoxylic nomads (I refuse to dignify them with the term “paleolithic” when they seem to be totally in ignorance of even the simplest stoneworking techniques, and to make all their tools out of scavenged tree branches) who live in a vast and heavily wooded valley. Vuud is also the presumptive heir to leadership of Great Zog’s Tribe (Great Zog apparently being the god they worship), the son of their chief, Iksay (Benito Stefanelli, from Battle of the Amazons and Castle of Blood). Iksay is thinking about retiring, too, but that isn’t nearly as good news for the ambitious Vuud as the latter man expects. Iksay has a rather low opinion of his son; he thinks he’s impulsive, impatient, impetuous, and several other negative things that begin with “imp,” that his leadership would imperil the tribe, and that it would therefore be impossible even to consider putting him in charge. Iksay’s preferred successor is Ela (Sam Pasco, who looks like he thought this was supposed to be a Conan rip-off, too), an altogether more thoughtful and even-tempered man whose exploits as a hunter and fighter are only slightly less impressive than Vuud’s. Vuud attempts an end-run around Iksay’s succession plan by killing his father during a boar-hunt, when he thinks he’s out of everybody else’s sight, and initially, Rag the shaman (Jacques Herlin, of Shaft in Africa and War of the Robots) seems to be the only member of the tribe much inclined to honor the dead man’s intentions regarding the chieftaincy. However, it turns out there was one witness to Vuud’s crime after all— Ela. Cleverer filmmakers than the present bunch might have made something of the obvious conflict of interest when the man who claims to have observed Iksay’s death just happens to have more to gain than anyone from seeing Vuud charged with murder. That’s not at all where Lenzi and company are going, though, and Vuud immediately responds to Ela’s accusation by attempting to kill him, too. However, the only person Vuud kills is Rag, who intervenes in the struggle in a futile attempt to deal with the situation calmly and rationally. With Vuud now unquestionably a slayer of his own people, Ela has no trouble getting a unanimous call for his banishment from the rest of Great Zog’s Tribe, and Vuud finds himself trekking off alone into the woods.

This being a caveman movie, there must perforce be an active volcano in the immediate vicinity of the characters’ homes, and Vuud happens to find himself with a front-row seat to its eruption one night after his expulsion from the tribe. Evidently having more curiosity than sense, the exiled hunter goes poking around in the lava field the next morning (I think we’re supposed to believe the thunderstorm that broke out halfway through the eruption quenched the magma’s heat with unusual rapidity), and he finds something very curious while he’s at it. Don’t ask me how, as physics and chemistry alike rather militate against this outcome, but among the cooling igneous rocks, Vuud finds an ingot of more or less pure iron, of just the right size and shape to act as a sort of crude sword. After pulling it free from the long, shallow depression that apparently molded it, Vuud starts swinging the ingot around and banging it on stuff, satisfying himself that it’s harder and stronger than any other object he’s ever seen. An encounter with a lion demonstrates the ingot’s effectiveness as a weapon, and then a shifty-eyed woman named Lith (Pamela Prati, from Transformations and The Adventures of Hercules) pops up out of nowhere to announce that the fire god Enferon sent her to tell Vuud that the iron is a divine gift. For that matter, Lith herself is evidently a divine gift, too. With her at his side and the ingot in his hand, Vuud has Enferon’s blessing to make himself master of the known world. (All 50 square miles of it…)

Naturally, Vuud aims to begin his conquest with his own tribe. Dressing himself up like a sad dimestore Hercules in the slain lion’s skin, he returns to his former home and picks a fight with Ela. Great Zog not being in the gift-giving business, Ela is no match for his old enemy, and his fellow tribesmen reveal themselves as a bunch of fickle cowards by immediately switching their allegiance to the man they so recently banished from their midst. Vuud orders Ela sent to the territory of the Ursus— an Ursu being some manner of aggressive australopithecine— where he is to be left bound and unarmed, with neither food nor water. Then, with that out of the way, the new chief leads his people back to the volcano, with the aim of finding more iron to create weapons for the whole tribe. And yes— that does indeed mean that these dimwits who never got the big lightbulb to stick sharpened bits of flint on the end of their spears somehow manage to develop iron-smelting techniques in what appears to be the space of about a week.

Ela, meanwhile, behaves once again as if he thinks he’s in the movie advertised in the box art, breaking free of his restraints in a manner suggesting a rather more plausible interpretation of Talon de-crucifying himself in The Sword and the Sorcerer. This he does just in time to get into a punch-up with a pack of Ursus, who will not be dining on retired bodybuilder tonight after all. Then he parallels Vuud’s experience in exile by meeting his love interest (who knew banishment was the key to romantic success?), in the form of a girl named Isa (Elvire Audray, from White Slave and Vampire in Venice), who luckily for Ela happens to be foraging for medicinal herbs at the time. You kind of have to wonder what Isa is doing all by herself without so much as an obsidian knife in the depths of Ursu country, but it’ll start to make a twisted kind of sense as soon as we’re introduced to her tribe; apparently they had hippy communes in the stone age, too. That won’t happen for a while yet, though. First, we have to get Ela and Isa away from the Ursus, and clue Ela in to what Vuud has Great Zog’s Tribe doing in his absence. Both those birds fall to the same iron ingot when Vuud and the gang inadvertently save Ela’s and Isa’s asses by massacring the Ursus as part of their escalating campaign to subjugate all the neighboring peoples.

If you’ve been paying close attention, then you’ll already see the final form of Ironmaster’s conflict taking shape. That’s right— it’s cave-warmongers vs. cave-hippies, with the whole subsequent course of human history as the ostensible prize! (Not to give everything away here, but the outcome of that contest suggests that history was not one of Lenzi’s stronger subjects during his school days…) With each new conquest, Vuud has more men and more weapons at his disposal, enabling him to achieve even greater conquests in the future, and amass thereby yet more men and yet more weapons, etc. Isa’s tribe, by contrast, are such radical pacifists that they not only eschew both hunting and the consumption of animal flesh, but even refuse to defend themselves or their fellows against attack by wild predators. (Extra credit question: If the cave-hippies neither hunt nor raise livestock, where exactly do they get the animal skins from which they make all their clothes?) Ela tries his best to convince Mogo, Isa’s dad and the hippy tribe’s leader (William Berger, of Devilfish and Golden Temple Amazons), of the necessity for arming his people in preparation for the attack that is sure to come as soon as Vuud notices their presence, but Mogo prefers martyrdom to betraying his principles. Fortunately for his followers, however, Mogo’s martyrdom is both literal and personal, creating an opportunity for Ela to organize the more pragmatic of the tribesmen into some approximation of a fighting force. Now all they need is a superweapon of their own that doesn’t require a fortuitous volcanic eruption— maybe something to do with those springy little trees over there…

I’ve noticed something very strange about caveman movies over the years. Nearly all of them attempt to dramatize the spread of some social or material innovation (fire, iron, farming, teamwork, simple human decency), and yet almost never do they depict their central characters actually inventing or discovering anything. Tumak in One Million B.C. (and in One Million Years B.C., too, while we’re on the subject) introduces the Rock Tribe to the seeds of civilization, but he does so by taking a mate from another tribe that long ago left behind what the classical economists used to call the state of nature. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth’s People of the Mountains abandon their brutal religion of human sacrifice, but only because Chief Points-and-Bellows gets swallowed up by a tidal wave, leaving Chief My-Toga-Is-Cooler-Than-Yours of the neighboring and much gentler Beach People the only man of shamanly standing available. The Neanderthals of Quest for Fire are taught how to make fire of their own by a Cro Magnon girl whom they rescue from a tribe of cannibals. And the utterly hapless primordial couple in Adam and Eve vs. the Cannibals can’t even figure out how to wield a staff worth a fuck without Eve’s headhunter boyfriend to instruct them! Consequently, I find myself feeling a bit of grudging respect for Ironmaster. However implausibly it does so, this movie has its protagonists discovering their own damn iron, inventing their own damn shortbows, and figuring out how to wage and/or reject war all by themselves. None of that means I wouldn’t still have much rather seen the totally awesome barbarian movie promised by the front of the video box, though.

This review is part of the B-Masters Cabal’s salute to caveman and barbarian movies, those films that did so much to usher cable-enabled boys of my age group into the perpetually suspended adolescence that passes for manhood among us. Click the banner below to read my colleagues’ takes on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact