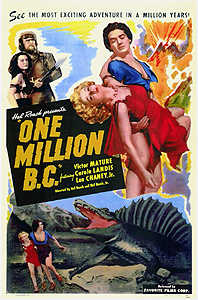

One Million B.C. / Man and His Mate / Cave Man / The Cave Dwellers / Battle of the Giants (1940) -**½

One Million B.C. / Man and His Mate / Cave Man / The Cave Dwellers / Battle of the Giants (1940) -**½

I would be very surprised to hear that more than a handful of my readers had seen One Million B.C. It rarely shows up on television anymore, it was never in very wide circulation on VHS, and so far as I can tell, it has yet to be released at all on DVD; consequently, it’s pretty damned obscure despite having been a huge hit at the box office in 1940, and having been famously remade by Hammer Film Productions in the mid-1960’s. Nevertheless, I put the odds at about nineteen in twenty that every single person reading this review has encountered some of One Million B.C.’s special effects footage at least once. I know of no other movie that has been so frequently and extensively raided by filmmakers who wanted impressive footage of battling dinosaurs and erupting volcanoes, but didn’t have the money in their budgets to pay for it. One Million B.C.’s biggest set-pieces— most notably the signature sequence in which a young alligator masquerading as a Dimetrodon wrestles with a large monitor lizard masquerading as I’m not really sure what— have turned up in so many movies that compiling a truly comprehensive list becomes a labor of film scholarship that could consume an entire lifetime: Prehistoric Women, Teenage Caveman, Robot Monster, King Dinosaur, Valley of the Dragons, Horror of the Blood Monsters, and heaven alone knows what else. At a further and extremely bizarre remove, When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth includes a meticulously staged reenactment of the infamous dino-fight. It’s a strange form of immortality with which the gods have favored Hal Roach’s antiquated caveman opus, but immortality just the same.

Curiously, Roach apparently lacked the confidence to jump right into the prehistoric action. Instead, One Million B.C. wastes a bit of time on a framing story that seems meant to assure us that the events to follow— or something very much like them, anyway— could easily have happened in the distant past. This assertion of scientific veracity might have been a trifle more convincing coming from a movie that didn’t have its primitive humans living side-by-side with dinosaurs. In the framing story, a group of mountaineering tourists in what I take to be Germany— how else to explain the guide’s lederhosen?— duck into a cave to seek shelter from a thunderstorm. When the guide (Robert Kent, from The Phantom Creeps and She Shoulda Said No) goes a little deeper inside (presumably to make sure the cave isn’t already being used by, say, a family of grizzly bears), he encounters an anthropologist (Conrad Nagel, from Kongo and The Thirteenth Chair) hard at work studying the ancient paintings that adorn the walls of the inner chamber. The scientist explains to his unexpected guests that the paintings actually tell a coherent story about the lives of the people who once lived in the cave, and since it’s not like they’ve got anything better to do, the tourists ask him to tell them all about it. (Cue universal flashback shimmer.)

The first cave-people we meet are obviously not the ones who created the paintings. In fact, the Rock Tribe (as our archeologist narrator dubs them) haven’t even gotten around yet to inventing very many useful things. Their most advanced tool appears to be the wooden walloping stick, and though they hunt in relatively large parties accompanied by domesticated dogs, they don’t go in for teamwork and the dogs don’t seem to serve any real function. As we see when Tumak (Victor Mature), son of Chief Akhoba (Lon Chaney Jr.), is turned loose to make his first kill, the rest of the mob just stands there on the nearest hill while the hunter in action brains his prey with his stick and/or wrestles it into submission, not taking any action until the issue is decided one way or the other. True, the system seems to work for them, as Tumak manages to bring down a baby Triceratops, but the Rock Tribe’s hunting strategy is so obviously inefficient that it comes as a major shock a bit later when we see that they know how to use fire. Organization within the tribe is on a strict might-makes-right basis, with the biggest bad-ass in the tribe calling all the shots and smacking down anyone who tries to disagree with him. Mealtime is an occasion for a free-for-all of thievery, intimidation, and physical violence, with the strongest members of the tribe getting whatever they want and the women, children, and elderly getting whatever is left. Nor do the Rock People have any notion of family loyalty, for Akhoba thinks nothing of trying to steal Tumak’s share after his own considerable portion leaves him unsatisfied. Tumak doesn’t back down, however, and father and son end up fighting with their sticks before the entrance to the tribe’s home cave. Akhoba wins decisively, but Tumak manages to slink away before his old man gets it into his head to come back down from the cave and finish him off.

Tumak’s subsequent travels bring him eventually to the home of a different tribe, which the archaeologist calls the Shell Tribe. This is an interesting point, because the Shell People obviously live nowhere near the sea, and yet those shells they use to make so many of their tools just as obviously come from marine mollusks. Don’t ask me. Anyway, the first member of the tribe to spot Tumak as he sleeps along the bank of their favorite fishing stream is a girl named Loana (Carole Landis). The sight of the strapping young stranger gets her excited, and she summons the rest of the tribe to help her bring him back to the cave where they make their home. This, in case you were wondering, is the cave where the tourists will encounter our narrator a million years or so hence, and on the off-chance that you’re curious about this, too, we’ll never see hide nor hair of that narrator again. Makes you wonder why they bothered with him in the first place. Regardless, Tumak’s trip to the Shell Tribe’s cave, and his hosts’ subsequent efforts to assimilate him, lead to what must surely be the only time any member of the Rock Tribe has ever contributed anything to the intellectual life of the species, for Tumak almost immediately discovers the phenomenon of culture shock. It isn’t just in such practical areas as tools and weapons that the Shell Tribe is dramatically more advanced than his own people, but in virtually every imaginable field of human endeavor. The Shell People have art. They have horticulture. They have jewelry and other decorative handicrafts. Most importantly, they have a social structure based on sharing and cooperation, and they quite obviously value skill and intelligence over brute strength— Loana’s father, Chief Peytow (Nigel De Brulier, from The Monkey’s Paw and The Hunchback of Notre Dame), wouldn’t last very long as a leader of the Rock Tribe.

Tumak tries his best to fit in with the Shell People, but it’s understandably very difficult for him. It certainly helps Tumak’s popularity that he has the strength to harvest bushels of fruit in mere seconds by shaking the trunk of a tree, or to defend the cave by going toe-to-toe with a man-in-a-suit teratosaur, but the possessiveness, greed, and distrustfulness that enabled him to survive among his own people get him into no end of trouble in his new home. He can’t seem to wrap his mind around the concept of property rights, and as soon as he figures out what a spear can do, he keeps trying to steal one from Loana’s sort-of boyfriend, Ahtao (John Hubbard, of The Mummy’s Tomb). Eventually, Tumak makes such a pest of himself that the Shell People, accommodating though they are, see no choice but to vote him off the island. Loana (the fickle bitch) goes with him when he sulks off into exile, however, and thus it is that Tumak is able to bring some measure of civilization with him when he returns to the haunts of the Rock Tribe. This works out especially well for Akhoba, who was wounded by a buffalo not long after Tumak’s banishment, and who has since been forced to cede the chieftanship to a younger man named Skakana (Edgar Edwards, from Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe). Indeed, one wonders how Akhoba has managed to survive at all, since it hardly seems as though his mate, Tokana (Monster from the Ocean Floor’s Inez Palange), is up to the challenge of protecting and supporting him. But even after Tumak asserts himself over Skakana and Loana introduces the Rock People to the boons of gardening, spear-making, and common human decency, let’s not make too rosy a prediction for the tribe’s future. I mean, what’s a caveman movie without an erupting volcano?

I’m of two minds— you know what? Let’s make that three— about One Million B.C. To begin with, the sheer dopiness of this movie is undeniable, and thence derives the vast bulk of its appeal. The go-nowhere framing story, the hapless stab at a made-up language for the cavemen, the iguanas and armadillos pretending to be dinosaurs, the various mad efforts to sell us on the legitimacy of the film’s desperately bad paleontology— in just about every way, One Million B.C. set the notoriously low standard for all the cheap-ass caveman movies to come. On the other hand, there is at least one respect in which producer Hal Roach Sr. and his writer/director son tried very hard with this picture. They wanted spectacle, and every penny of the admittedly inadequate budget unquestionably wound up on the screen. When seen in its original context, the frequently reused dinosaur footage is actually sort of impressive in the sense of being very well integrated with the surrounding non-miniature material. When the giant iguana lays siege to the Shell Tribe’s cave during the second half of the climax, nobody would ever mistake it for anything but an iguana, but damned if it doesn’t look like it really is 70 feet long and standing right there in the thick of the action. Honestly, it isn’t so hard to imagine, after seeing One Million B.C., why so many would-be purveyors of B-grade monster flicks over the next 30-odd years would come here to have their dinosaur needs seen to. The Roach gang sure as hell made a better go of it than the makers of 1960’s The Lost World!

But then there’s that third mind I mentioned, one last issue that needs to be addressed: One Million B.C. is not a film for animal lovers. Indeed, it really ought to conclude with a notice reading, “No animals escaped harm during the making of this picture.” You know that shot in King Kong where Carl Denham leads his men past the gigantic body of the dying Stegosaurus? Well, something very similar happens here, only it’s a real monitor lizard rather than a rubber Stegosaurus, and it really is dying! As Tumak and Loana traverse the jungle between the two tribes’ homes, they are menaced by a giant snake. Their salvation comes when the serpent is killed (for real) and eaten (for real) by something even bigger and fiercer. The iguana battle ends with the lizard being buried beneath a landslide, and once again an animal is subjected to treatment that I can’t imagine it surviving— although that time we aren’t explicitly presented with the death-throes. It’s almost worthy of Ruggero Deodato, and anyone considering giving One Million B.C. a look should think seriously about whether that’s something they’re prepared to watch.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact