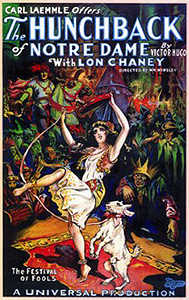

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) ***

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) ***

Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame stands among the all-time grand champions in the “When will you people finally get tired of filming this story?” stakes. If we count the Walt Disney version from 1997 (as I suppose we must), I know of at least 13 cinematic adaptations of the novel, going all the way back to 1906’s Esmeralda. (Incidentally, that total includes a couple versions inexplicably made in India!) But of all the multitudinous Hunchback movies, the two that people remember best today are the 1939 RKO version with Charles Laughton and Universal’s 1923 silent rendition featuring the legendary Lon Chaney Sr. in the title role. In my estimation, the ‘39 version is pretty sorry taken as a whole, with Laughton’s fine performance providing its only redeeming feature. The older Universal film, on the other hand, is far superior, though I don’t hold it in nearly such high esteem as is customary among movie critics.

The first thing that is likely to strike most modern viewers about The Hunchback of Notre Dame is the completely alien approach that it takes toward character development. Movies today are expected to introduce their characters gradually, using dialogue and interaction to reveal their personalities. In the silent era, this was all but impossible because of the limited amount of text that could be presented legibly on a single intertitle. With dialogue necessarily sketchy and restricted only to those ideas that simply could not be conveyed by actions or gestures, silent filmmakers often accompanied the introduction of a new character with a title card that briefly synopsized that character’s salient qualities. This technique was especially common in films that had large casts, and since The Hunchback of Notre Dame has more characters than it quite knows what to do with, those descriptive intertitles appear in it with extraordinary frequency.

All the introductions slow the narrative to a crawl during the first third of the film, but the important points are as follows: During the reign of the tyrannical Louis IX, in Paris’s famous Notre Dame Cathedral, there lives a deaf, half-blind, hideously deformed man named Quasimodo (Lon Chaney, from The Monster and London After Midnight). Quasimodo works as the cathedral’s bell-ringer, and the reason he lives in the church as well is that the fear and hatred his deformities inspire in those who see him is such that he is effectively barred from living among “normal” people. It’s also worth keeping in mind that Quasimodo despises the world at least as much as it despises him. The Archdeacon of Notre Dame (Nigel de Brulier, from Ghosts and The Monkey’s Paw) has a brother named Jehan (Brandon Hurst, whom we’ve also seen in White Zombie and Murders in the Rue Morgue), who is rather less than saintly. Though the point is never made explicitly, it seems plausible that Quasimodo’s slavish devotion to Jehan stems from the hunchback’s recognition and approval of the contempt in which the single-mindedly self-interested Jehan holds the rest of the human race.

King Louis’s reign is a troubled one. His cruelty has given rise to a rival power structure, a swarming multitude of beggars, thieves, and vagrants whose leader, Clopin (The Unholy Night’s Ernest Torrence), is slowly forging them into an army of proto-communist revolutionaries. Clopin has a foster daughter named Esmeralda (Patsy Ruth Miller), whom he bought from a band of Gypsies when she was just a toddler. At the annual Feast of Fools— a sort of national holiday for the Lumpenproletariat of France, which is grudgingly tolerated by the king and his ministers— Esmeralda’s dancing attracts the attention of two people who will come to be very important in her life. One of them is Quasimodo, whom she meets when the revelers bestow upon him the dubious honor of crowning him King of the Fools, a distinction which the crowd gives each year to the ugliest man that can be found. The other is Phoebus de Chateaupers (Norman Kerry, who later played alongside Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera and The Unknown), King Louis’s captain of the guards. Phoebus is instantly smitten with Esmeralda, and will spend the rest of the movie blowing off his long-suffering fiancee in a quest to get into the gypsy girl’s pants.

A bit later, Esmeralda acquires another admirer, one whom, given the choice, she’d almost certainly rather not have. This is Jehan, who sees the girl when she comes to the cathedral to meet Phoebus. That very night, Jehan sics Quasimodo on Esmeralda, but the hunchback is foiled in his kidnapping attempt by the captain of the guards, who arrests him and sends him off to one of the king’s nastier jails with a detachment of soldiers, while he and Esmeralda go off to the nearest tavern to drink and make out. (And by the way, Patsy Ruth Miller has amazingly sexy shoulders.) This leads us ultimately to one of The Hunchback of Notre Dame’s pivotal scenes, the public flogging of Quasimodo. The hunchback is sentenced to 50 lashes and an hour in restraints in the public square. Near the end of his punishment, Quasimodo begins calling out for water, but everyone in the square is having too much fun watching him suffer to give him any. Everyone, that is, except for Esmeralda, whose unexpected act of kindness wins her the hunchback’s undying affection.

This will come in handy later, because Esmeralda is about to have the worst kind of run-in with the authorities. Jehan still desperately wants Esmeralda for himself, and after his abduction scheme fails, he turns his attention to other avenues. First, he tries to buy the girl from Clopin, suggesting that the treasure of Notre Dame Cathedral could turn the “King of the Beggars” into a real leader of men. Clopin doesn’t agree to Jehan’s bargain, but then again, he doesn’t exactly say no, either. Jehan is an impatient man, though, and he eventually gets tired of waiting and tries to kill Phoebus, thereby eliminating his competition. This plan goes wrong on so many levels it’s not even funny. Not only does Esmeralda not suddenly fall into Jehan’s arms after he stabs Phoebus (well, duh...), Phoebus himself has the inexcusable temerity not to die! What’s more, Esmeralda ends up getting charged with the attempt on the captain’s life, and is tortured into confessing to the crime. (Note that this scene employs a little-known, but highly effective medieval torture device: the boots. This instrument was clamped around the victim’s feet and tightened by means of a long iron screw. More than a few minutes in the boots and there wouldn’t be enough left of your ankle bones to make beads out of.) Quasimodo reenters the picture when he sees Esmeralda saying her final prayers, surrounded by soldiers on the front steps of the cathedral. Remembering her as the girl who gave him a drink when he was tied up in the square, and making the connection between her presence at the cathedral and the death-knell he had been ordered to ring an hour or so before, the hunchback literally swings into action, dropping down to the steps on a rope, and then carrying Esmeralda to safety on the roof.

And thus the stage is set for the climactic battle in the square before the church. Clopin, having been told by Jehan that his foster daughter was imprisoned in Notre Dame, raises up his army and leads it in a siege of the cathedral. Phoebus, now minimally recovered from Jehan’s attempt on his life, rides with his men to oppose Clopin’s attack. And Quasimodo, for his part, mistakes everybody on the streets below for the policemen whom he expects to come looking for Esmeralda at any moment, and rains down stones, timbers, and molten lead left by the workers repairing the cathedral roof on beggars and guardsmen alike. Finally, Jehan makes one last, desperate play to possess Esmeralda, and learns first-hand that on Quasimodo’s shit-list is a bad place to be. The final outcome of all this mayhem isn’t so mercilessly bleak as it is in Hugo’s novel, but it doesn’t take nearly as many liberties with the story as the 1939 version, with its concluding round of happily-ever-afters for all.

You can really tell the folks at Universal pulled out all the stops for this one. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a review of The Hunchback of Notre Dame that didn’t say something about the film’s “epic scope” or “sweeping grandeur,” and this is one of those rare instances in which I’m inclined to add my voice to the chorus of mainstream critical opinion. This movie is just fucking impressive, proving by its example that there is occasionally a good reason to spend as much money as the majors do when they’re putting together a picture. Everything from the sets to the costumes to the most insignificant prop looks exactly right, and the thronging extras effectively transform the back-lot stages where most of the filming took place into a convincing approximation of a vibrant European city.

The most impressive thing in the movie, however, is Lon Chaney himself. The man is simply unbelievable. Not only does he portray his character more persuasively than any actor since, despite having no audible dialogue and having his entire face obscured or distorted by elaborate makeup, he also devised that memorable makeup himself. What’s more, he puts on an awesomely athletic performance, especially when you consider that the body suit he wore to give him the hunchback’s ape-like build weighed a full 70 pounds. Try climbing eight or ten feet up a rope in so cumbersome a getup, then hanging from it upside down by your ankles, and see what you get! And according to contemporary reports (although this has been disputed since), Chaney also did all his own stunts— in full hunchback regalia, mind you— which, in light of all the time he spends climbing around on the cathedral facade, is absolutely staggering. (And even if it wasn’t Chaney himself, somebody sure put in a lot of hours scrambling up and down the sets in that hunchback getup. Whoever it was, that guy gets my undying respect.)

Where The Hunchback of Notre Dame goes wrong is in trying to pay lip service to every piddling little subplot in the novel. Most mass-market paperback editions of The Hunchback of Notre Dame are close to two inches thick; there’s just no way to turn such a story into a 90-120-minute movie without leaving a lot out. Usually, this kind of streamlining is accomplished by jettisoning extraneous characters, subplots, and minor twists to the main story. Not so with this movie. What director Wallace Worsley and writers Edgar T. Lowe Jr. and Perley Poore Sheehan have done instead is reduce the screen time devoted to such things to the bare minimum necessary to establish their presence in the story. This is likely to leave most audiences scratching their heads at the relationships among whole phalanxes of characters whose actions have little or no apparent impact on the plot. For example, it is entirely possible to tell this story without once making reference to the failed poet Gringoire (Raymond Hatton, who can be seen near the other end of his life in The Day the World Ended and Invasion of the Saucer Men), or to the madwoman who turns out to be Esmeralda’s long-lost mother— as indeed I have. The latter character’s entire purpose in the movie is to snatch away the girl’s necklace as she is led off to her intended execution, only to recognize it as the one she gave her baby daughter on the day the child was stolen by Gypsies. Yet even when it comes, this revelation has no effect on the story whatsoever. With time constraints pressing down on the story, it would make much more sense just to ditch this character, and use the ten minutes or so gained thereby to further develop the character of Jehan, who, as the main villain, really ought to have a bit more to do.

But that aside, this version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame remains the one to see. It has all the high-dollar production value of the 1939 version, an even hotter Esmeralda, and a far more thematically honest spin on the basic story. Plus, it has Lon Chaney in one of his best roles, which ought to be enough all by itself.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact