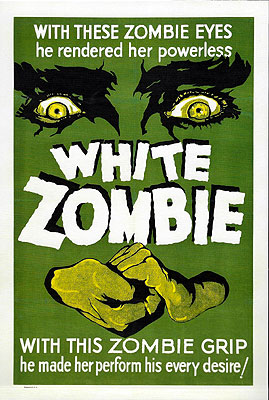

White Zombie (1932) ***Ĺ

White Zombie (1932) ***Ĺ

Considering how flabby and bloated and senile the Hollywood studio system is today, it is scarcely surprising that much of the creative energy in modern cinema flows from independent filmmakers and minor studios, especially in genres like horror and science fiction, whose audiences have historically been peculiarly forgiving of tiny budgets and the limitations they place on a movie. But as White Zombie demonstrates, the independents were already learning to outmaneuver the big boys as early as 1932. White Zombie was, to the best of my knowledge, the very first voodoo movie, and some 70 years later, it remains one of the best. Though it is rather slow-moving and looks decidedly creaky today, it is also beautifully composed, technically groundbreaking, and blessed with what is probably the second-best performance of Bela Lugosiís mostly unimpressive career.

Like so many other 1930ís horror movies, White Zombie begins with a pair of young lovers arriving in a strange place, far from their homes. The coupleís names are Neil Parker (John Harron) and Madeline Short (Madge Bellamy), and they have come to Haiti to be married. I grant you, when I think ďHaiti,Ē romance is not the first thing that springs to mind, but Parker and his fiancee have a pretty good reason. It turns out a man named Charles Beaumont (Robert Frazer, from The Vampire Bat and Black Dragons), who met Madeline once on a boat ride to someplace or other, took such a liking to the girl that he not only got her boyfriend a job with his company, he also paid to have them both shipped out to his Haitian sugar plantation so that they could be married and spend their honeymoon in a ďtropical paradise.Ē Yeah, and if you believe that...

The first indication of trouble comes on the carriage ride out to Beaumontís place. The coachman is forced to stop when he comes upon a funeral service being conducted in the middle of the road. As he explains to his mystified passengers, the body is being buried in the road in order to protect it from those who would steal it; apparently thereís been a lot of that going around lately. Shortly thereafter, the driver sees a man standing by the side of the road, and stops to give him a lift. But when a small gang of stiff-limbed men shamble out of the underbrush all around him, driver realizes who it is he has just met, and frantically whips his horses to a swift trot. Before the coachman can get away, however, the man by the roadside seizes hold of Madelineís shawl, and the garment remains in his hand when the carriage speeds off down the road. When the driver has put a safe distance between him and the shawl-thief, he explains that the stranger was a notorious voodoo priest, and that his gang of pasty-faced thugs were zombies, the re-animated bodies of dead men, stolen from their graves to work as slaves in the witch doctorís sugar mill. I can think of better ways to begin a honeymoon than this.

It only gets worse when the travelers reach their destination. Beaumontís butler, Silver (Brandon Hurst, from Murders in the Rue Morgue and the 1920 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), is one of those B-movie servants who look like their first words to the guests ought to be, ďGood evening, sir... madame. Will you be dining in the evil or non-evil section tonight?Ē And whatís more, when he tells his master that Neil and Madeline have arrived, Beaumontís first impulse is to pretend he isnít in! Thatís never a good sign! Then, while the couple waits for their host in the parlor, talking to Dr. Bruner (Joseph Cawthorn), the missionary who is slated to officiate at their wedding, the old preacher tells them in no uncertain terms that Beaumont is not to be trusted. The manís behavior when he finally does come downstairs gives good reason to take Brunerís warning seriously. Beaumont simply will not leave Madeline aloneó youíd think heíd brought the girl in to marry him!

And soon thereafter, we learn that he pretty much did. While Silver is hustling the guests upstairs to their rooms, another visitor arrives. A strange, silent man with a one-horse carriage has come to collect Beaumont for an appointment with his boss. Do you really need to be told that the man Beaumont wants to see, the alarmingly named Murder Legendre (Bela Lugosi), is the witch doctor with whom Neil and Madeline had their run-in on the ride to the plantation? No. I didnít think so. The zombie coachman leads Beaumont through Legendreís sugar mill (the sight of the living dead processing the sugarcane is actually pretty creepy the first time around) to the witch doctorís office. There, he and Beaumont discuss the planterís desire to have Madeline bewitched so that she will abandon Neil, and fall in love with Beaumont instead. Legendre tells him that there isnít time for a conventional love-charm to work before the marriage the next day, but that there is still one way for Beaumont to claim Madeline as his own. Watching this today, we of course know exactly what Murder is driving at, but when this movie was made, most Americans had scarcely heard of voodoo or zombies, and the way in which the conversation skirts the issue would probably have been a marvelous tension-builder. Beaumont doesnít much like the idea of turning Madeline into a zombie, but Legendre makes him take a vial of his voodoo drug with him, anyway, so that it will be there for him in the event that Beaumont changes his mind.

He does, of course. That night, when an impassioned plea to Madeline fails to change her allegiance, the planter gives her a rose dusted with Legendreís zombie powder, which she naturally sniffs, filling her lungs with the unsavory drug. And shortly after the marriage, Murder himself comes to the Beaumont estate with a wax effigy of Madeline, around which he has wrapped the young womanís shawl. When Legendre burns the effigy out in the garden, Madeline sees the witch doctorís face reflected in her wine glass, and keels over dead on the spot.

Neil spends most of day of his brideís funeral drinking himself stupid. But he keeps having visions of Madeline, and when he follows one of them to the girlís tomb, he arrives only just too late to interrupt Beaumont, Legendre, and a pack of zombies making off with her coffin. When he finds the plundered crypt, Neil does the sensible thing, and goes straight to Dr. Bruner, whose experience with the natives makes him seem the natural person to deal with the situation. Neil isnít terribly pleased with what the preacher has to say, however. As Bruner explains, there are just two possibilities. Either Madelineís body is currently being ground up and rendered into voodoo potions, or even worse, the girl wasnít really dead at all, and she is being turned into a zombie like those that labor in Murder Legendreís sugar mill. Either way, Bruner knows what to do. One of his closest friends on the island is a witch doctor himself, and should be able to tell him who might have taken Madeline and why.

Meanwhile, back at the partially ruined seaside castle where Legendre makes his home, Beaumont is having second thoughts about the whole zombie girlfriend thing. Madeline turns out not to be nearly so much fun as a walking corpse, and Beaumont begins pestering Legendre to change her back. The voodoo priest, for his part, doesnít much care for the idea. Heíd much rather equalize the couple by turning Beaumont into a zombie too! But that little double cross ends up being Murderís undoing, in that the planterís transformation isnít quite complete when Neil and Dr. Bruner come calling, meaning that Legendre will have a fifth column on his hands when he squares off against his enemies. And luckily for Neil, and Madeline even more so, zombification turns out to be reversible if you catch it early enough.

White Zombie is often called the original zombie movie. While itís true that this is the first movie Iím aware of to feature zombies, the person who comes to White Zombie looking for some pre-Hays Code gut-munching will be sorely disappointed. The zombie as cannibal corpse is solely the invention of George Romero, and the zombies here are played strictly according to Caribbean folklore. The threat isnít so much what the zombies themselves will do to you, but rather that their creator may make you one of them. Even so, White Zombie is probably the creepiest 30ís-vintage horror movie Iíve ever seen. The mood of menace conveyed by the carefully considered set design and somber, deliberately inadequate lighting equals the very best that Universalís directors could come up with, while the innovative camera work and special visual effects rival that of the German expressionists of the 20ís. The movie also holds up better than most of its contemporaries in that it somehow avoided the cornball sentimentality and overly stylized, stagy performances so characteristic of early-30ís films. Director Victor Halperin even discovered, nearly a decade before anyone else, the secret to getting a decent performance out of Bela Lugosi: donít give him more than a couple of lines to deliver at a stretch. And best of all, White Zombie was subjected to a major restoration in 1999. The restored version still has a few scratches and missing frames, and the soundtrack is still too quiet, but by all accounts, itís a great improvement over the sorry condition in which the movie generally appeared before. In short, White Zombie is one of the crowning glories of the first decade of American horror cinema in the sound era, and anyone who, like me, has a generally low opinion of very old Hollywood horror movies definitely ought to give it a look.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact