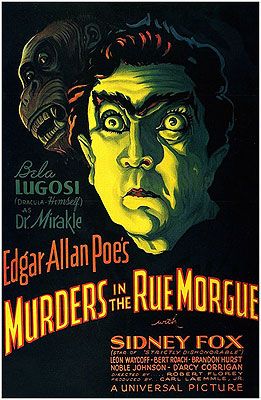

Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) -***

Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932) -***

Murders in the Rue Morgue was the first of a handful of short, dopey, Poe-inspired movies released by Universal Studios in the 1930’s, featuring Bela Lugosi in much the same way that A.I.P.’s Poe films would feature Vincent Price 30 years later. And for reasons that I will go into shortly, I’d be willing to wager substantially that Murders in the Rue Morgue was also one of Ed Wood’s personal favorite movies.

As you probably realize, Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue” was the first modern detective story. As a murder mystery, it’s a terrible cheat (the culprit turns out to be, of all things, an escaped orangutan!), and as Poe wrote it, it doesn’t stand up terribly well as horror, either. But the story seems like it could easily be turned into a perfectly serviceable horror flick with a bit of tinkering, and filmmakers have been attempting to do exactly that for generations. What gets them into trouble is the precise nature of their tinkering, which more often than not has led to utterly ludicrous results. Case in point: In this version, screenwriters Tom Reed and Dale Van Every have turned Poe’s already loopy story into the tale of a mad scientist, his “talking” ape, and his efforts to prove that man is indeed descended from simians, apparently by mating Eric the gorilla with a French virgin. Wow.

The virgin in question is Camille L’Espanaye (Sidney Fox). As the movie begins, Camille, her med-student boyfriend Pierre Dupin (Leon Waycoff, who, under the name Leon Ames, had a long and fruitful career that carried him to the heights of Tora! Tora! Tora! before finally sinking him to the ignominy of Claws), Pierre’s roommate Paul (Bert Roach, of Dr. Renault's Secret), and Paul’s girl Mignette (silent actress Edna Marrion, in her last film role), are all taking in the rowdy entertainments of a traveling carnival. After passing up “Arabian” belly dancers, “savage” American Indians, and a couple of lesser attractions, the four carnival-goers are finally seduced by the charms of Eric the Ape-Man, “Lord of the Jungle.” They pay their admission and take their seats in the tent of Dr. Mirakle (Bela Lugosi, whom the makeup department has endowed with an amazing afro and a single immense eyebrow), who claims to have captured Eric in darkest Africa and learned to speak the ape’s primitive language. Mirakle’s show certainly is a hoot. To begin with, I should mention that Eric is portrayed by a real chimpanzee (albeit a female one) in close-up, but from a distance, he’s played by a man in one of history’s worst gorilla suits. Secondly, his “primitive language” sounds pretty much like your standard-issue simian grunting and squealing to me, even though Mirakle is clearly speaking some kind of language when he addresses the ape. (What do you want to bet Mirakle’s commands to Eric are in Lugosi’s native Hungarian?) Finally, there’s the fact that Mirakle and Eric have no real act. Mirakle just stands up on the stage beside Eric’s cage and spouts off about how Eric is “the first man,” and how he intends to prove this outlandish assertion (Murders in the Rue Morgue is set just shortly after the publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species) by mixing Eric’s blood with that of a human. Mirakle’s outre pronouncements have the effect of emptying the tent of everyone save Camille and her friends, and the doctor invites the four of them to come have a closer look at Eric. When they agree, the ape “asks” for Camille’s bonnet, and when Pierre tries to get it back a moment later, Eric tries to strangle him. Mirakle calls the ape off, and offers to replace Camille’s bonnet, but Pierre doesn’t want the girl giving Mirakle her address. Mirakle obviously has some kind of designs on her, however, because he sends his assistant, Janos (The Most Dangerous Game’s Noble Johnson, who also played the island chieftain in King Kong), to follow her when she and her friends leave.

We get some idea of what Mirakle’s intentions are in the next scene, when he picks up a prostitute (after a very confusing knife fight between two men whose connection to neither Mirakle nor the hooker is ever explained) and takes her back to his secret laboratory, hidden away in the attic of an abandoned building in downtown Paris. There, he ties the girl up, and gives her a series of injections of Eric’s blood. These ape-blood injections kill the hooker, apparently because she isn’t a virgin. Now, as we shall soon learn, this is the third girl Mirakle has tried this on; if the problem is the virginity or lack thereof of his test subjects, what the hell is the doctor doing using prostitutes in his research?! I don’t know about you, but it seems to me that virgin whores would be just about the rarest things on Earth! His latest experiment a failure, Mirakle orders Janos to dump his victim’s body in the river.

The cops fish her out not much later, and just minutes after her arrival at the morgue, Pierre Dupin comes calling to have a look at it. Apparently Pierre is an amateur detective as well as a med student, and he has lately been amusing himself by trying to solve the mystery surrounding the recent spate of hooker slayings. The coroner (the appropriately cadaverous D’Arcy Corrigan, from The Last Warning) won’t let Dupin draw any of the latest victim’s blood (something about a body-snatching scandal involving another medical student), but a small bribe convinces him to draw some himself and deliver it to Pierre the next day. When Pierre gets a chance to compare this blood with samples he took from the earlier victims, he notices that all three girls had their blood contaminated with some foreign substance. Pierre rightly concludes that this, whatever it is, is what killed the hookers.

Meanwhile, Dr. Mirakle’s interest in Camille continues unabated. Using the address Janos discovered for him, he sends Camille a lavish new bonnet to replace the one Eric took. Enclosed in the package is a note requesting that she come to the carnival to talk to him that night, and though Camille herself sees nothing wrong with going to see the doctor, Pierre objects, insisting on going in her place to present her thanks to Mirakle. Smart move, that, but the doctor is not so easily dissuaded— apparently Eric has a really serious crush on Camille, and the mad scientist thinks it wise to make sure the subject of his next experiment meets with the gorilla’s approval. He goes to Camille’s apartment late that night and tries to talk her into coming with him to his place. When she refuses, making no secret of the fear and loathing that Mirakle’s visit has inspired, the doctor retreats, and then sends Eric up to collect the girl himself. Pierre, who happens to be walking in the vicinity of Camille’s building when the ape breaks in, is one of the first to come rushing to his girlfriend’s aid. But the door to the apartment is locked, and by the time the police arrive to help him break down the door, it is already too late. Eric has absconded with Camille, and there is no sign of the girl’s mother anywhere in the flat, either. And apparently, we are dealing here with the most incompetent policemen in all of France, because they immediately arrest Pierre, despite the obvious fact that they saw him outside the flat, trying to break in and come to the rescue at the very moment the crime was being committed!!!!

It is at this point in the film that something truly amazing happens: a scene transpires that actually appears in Poe’s story! The prefect of police (Brandon Hurst, from White Zombie and the 1920 version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) comes to interview everyone in Camille’s building regarding what they saw and heard just before the girl and her mother disappeared. As in the story, there are three foreigners, all of whom claim to have heard a voice in Camille’s flat, speaking in a language that they don’t understand (the German thinks it was Italian, the Italian thinks it was Danish, and the Dane thinks it was German— this scene makes a hell of a lot more sense in Poe’s version, which has the murder take place in a hotel room rather than a private apartment); as in the story, Camille’s mother is found dead, her body stuffed into the chimney; and as in the story, the victim’s dead hand is clutching a tuft of ape fur. When Dupin points out the fur in the dead woman’s hand, even the police prefect (who would clearly really like to be able to charge Pierre with the crime and go home) is forced to believe his prime suspect’s story that an ape is to blame, and he and his men somewhat reluctantly follow Pierre to Mirakle’s hideout. (Funny— I don’t remember Pierre ever learning where it was...)

The conclusion to Murders in the Rue Morgue is more than a little hard to follow, but suffice it to say that the police arrive just after Eric kills Mirakle for no readily apparent reason, grabs Camille, and runs off with her across the rooftops of Paris in a sequence stolen directly from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. (Come to think of it, this scene also foreshadows the final act of King Kong, and indeed even features one shot that was accomplished through stop-motion animation.) Pierre races off in pursuit, and finally corners the ape on the roof of a small dockside house, shoots it dead after a brief but riotously funny confrontation, and saves Camille from her peril.

What makes me think Murders in the Rue Morgue was a seminal influence on Ed Wood is a combination of its remarkable echoes of Wood’s own work, and the well documented fact that Wood was a huge Bela Lugosi fan, and could thus be counted upon at least to have seen it. Hints of Bride of the Monster and Plan 9 from Outer Space are everywhere in Murders in the Rue Morgue: in the script’s abject disregard for logic, in director Robert Florey’s equally abject disregard for clarity, and most of all in one of the most amazing displays of pompous, nonsensical dialogue I’ve ever encountered in a movie that neither Wood nor Al Adamson (that other towering figure of the “what the fuck?!” school of dialogue) was involved in. Lugosi, of course, has most of the best lines (and I defy you to listen to him tell Pierre that “this tent is my home” without flashing on Lugosi’s famous “The jungle is my home!” speech from Bride of the Monster), but just about everyone who has any dialogue at all gets a crack at bewildering the audience. Obviously, Wood’s famously cheapjack production values are not in evidence, but everything else that makes his work so distinctive can be seen in a more subdued form here. I’m frankly amazed that Murders in the Rue Morgue has never developed the sort of reputation that Lugosi’s astoundingly dumb Monogram movies from the 40’s (the most direct ancestors of his work for Wood) have today.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact