The Vampire Bat (1933) **½

The Vampire Bat (1933) **½

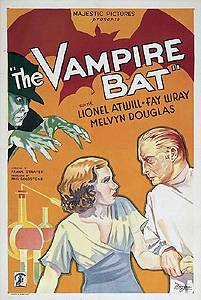

No, I can’t say I’d ever heard of Majestic Pictures, either. A tiny, cheap-ass studio that doesn’t seem to have survived the 1930’s, Majestic appears to have made just this one noteworthy contribution to the first Hollywood horror boom. And make no mistake, The Vampire Bat is definitely noteworthy, even despite its obscurity. Though it was quite transparently designed to cash in on the success of the early Universal films, it’s actually a good deal better than many of them, and director Frank R. Strayer displays vastly more imagination in his handling of the project than any of the filmmakers who made horror pictures for the bigger studio in those days. It is also an important early example of the proud B-studio tradition of scooping the majors; work on it was begun just after shooting wrapped on Warner Brothers’ high-profile The Mystery of the Wax Museum, employing two of that movie’s leading actors, but Majestic managed to get it into the theaters well before Warner were done putting the finishing touches on their production.

There’s big trouble in the small, generically Germanic village of Kleinschloss. Between a rash of strange exsanguination murders and the sudden appearance in town of a horde of unusually large and aggressive bats, the villagers have come to fear that they are under attack by a vampire, and even some of the leading citizens have begun to take the superstitious mutterings seriously. At the home of Burgermeister Gustave Schoen (The Unholy Night’s Lionel Belmore, who also played the burgermeister in Frankenstein), a meeting is underway between the mayor, several of the city fathers, and police detective Karl Brettschneider (Melvyn Douglas, later— much later, actually— of Ghost Story and The Changeling), whereby Schoen hopes to hammer out a solution to his town’s woes. Brettschneider, virtually alone among those in attendance, ridicules the notion that there is a vampire in Kleinschloss. Although he concedes that the circumstances of the killings are strange indeed, he is quite certain that the murderer he seeks is perfectly human, and he has no patience for stories about evil men coming back from the grave to turn into bats and drink the blood of the living. Basically, the main thing that the policeman takes away from the meeting is a heightened sense of urgency— he’d better catch the real murderer soon, or who knows what havoc the unleashed atavistic fears of the townspeople might cause.

After the meeting breaks up, Brettschneider goes to unwind and vent his frustrations with his girlfriend, Ruth Bertin (Fay Wray, from Black Moon and The Most Dangerous Game). Ruth lives with her hypochondriacal aunt, Gussie Schappmann (Maude Eburn, of The Bat Whispers), and both women have some unexplained tie to a scientist named Otto von Niemann (Lionel Atwill, from Man-Made Monster and The Strange Case of Dr. Rx). I’m not sure why, but von Niemann lives with Gussie and Ruth, and they have even allowed him to construct an extremely impressive mad lab in their basement. Evidently von Niemann is a medical doctor as well as a biochemist, because he frequently winds up on hand to help deal with the aftermath when the Kleinschloss Vampire Killer strikes. He also takes less grisly medical calls, as when he tends to a sick old lady named Martha Mueller (Rita Carlyle), who is apparently one of the very few people in town who is friendly toward Herman Gleib (Dwight Frye, who had played pretty much the same character in Dracula, and would do so again in Dead Men Walk), the village bug-eater.

That friendship threatens to get Herman into very hot water, because when the Vampire Killer slays Martha that night, there are several witnesses to the fact that Herman was among the last to see the old lady alive, and that he made a point of giving her a flower before he left. Because Herman displays a curious affection for the gigantic bats that everyone else hates and fears so much, even to the extent of letting dozens of the things roost in the garret apartment where he makes his home, there are those in Kleinschloss who believe that Gleib gave Martha that flower as a sort of homing device to mark her out as the vampire’s next victim. Others, like Mr. Kringen (Jungle Hell’s George E. Stone), cut right to the chase, and contend that Herman himself is the vampire. It’s all Schoen and Brettschneider can do to restrain Kringen from putting together a lynch mob to behead Gleib and drive a wooden stake through his heart, and when Kringen himself turns up dead, the job only gets harder. On the other hand, Brettschneider is so desperate at this point that he’s now willing to give the vampire hypothesis a fair hearing, especially after von Niemann assures him that a man might exhibit vampire-like behaviors for purely natural reasons. Eventually, Karl breaks down, and authorizes one of his louder critics to assemble a search party to catch Herman and bring him to the village jail to await trial.

While that’s going on, we’re seeing that Brettschneider, Schoen, and everybody else have done nothing but set off on a wild goose chase— it’s really von Niemann they should be locking up. The Kleinschloss Vampire Killer is his assistant, Emil (Robert Frazer, from White Zombie and Black Dragons), whom he somehow hypnotically controls in order to round up raw materials for a secret experiment he’s been conducting. Emil chloroforms his victims while they sleep, then carries them back to the lab, where his boss hooks up a blood-extracting machine to their jugular veins, producing the distinctive dual puncture wounds on the throat that got everybody in town crying “vampire” in the first place. The reason von Niemann needs the blood is that he has created some sort of artificial organism, a blob of synthetic flesh which he keeps in a tank of transparent fluid in his lab, and human blood is the only food this creature is capable of digesting. In other words, the real action has been going on right under Brettschneider’s nose all along, and there’s a very good chance that his girlfriend and her aunt will end up embroiled in it sooner or later. After all, although the victims are invariably returned to their beds afterwards, the scene of the real crimes is in the women’s own cellar.

The Vampire Bat is an unexpectedly effective film. Although it is completely unapologetic about copying both Dracula and Frankenstein, the recycled elements are combined in a highly imaginative way that seems to reflect a much clearer and more developed understanding of what a horror film could be than either Tod Browning or James Whale possessed in 1931. And while the recasting of traditionally supernatural horror commonplaces— werewolves and zombies especially— as the products of mad science would become a recurring theme of poverty-row fright films in the 1940’s, few of those later movies would wed science to the supernatural with anything like the degree of care and craftsmanship on display in The Vampire Bat. Von Niemann’s technology-driven vampirism has an internal logic to it which is extremely rare among very old horror films (except for that part about using Emil as a remote-control killer— that’s just plain silly), and the real nature of his research, when it is finally revealed, is both commendably ghoulish and commendably different from the earlier cinematic mad science which so obviously inspired it.

I also have to applaud Frank Strayer’s direction. Like most of the early horror talkies, The Vampire Bat is exceedingly, well, talky, but Strayer does a good job of minimizing the damage caused thereby. He has a great eye for frame composition, he makes deft use of some unconventional transitional techniques between scenes, and most importantly, he keeps the camera moving, panning and zooming and winding busily around the set. Taken together, these techniques frequently create the illusion of action in scenes that are really nothing but blather, preventing The Vampire Bat from ever becoming as rickety and top-heavy as it probably would have been in the hands of just about anybody else on the scene in the early 1930’s. Certainly, he makes much better use of the sets rented from Universal (Gussie’s place was definitely Femm Manor in The Old Dark House, and I know I’ve seen the streets of Kleinschloss before, even if I can’t place them specifically) than their owners did the first time around. It’s just unfortunate that The Vampire Bat had so much need of Strayer’s ability to suggest action that isn’t actually happening, so many shortcomings of pace to be covered up. With a busier script and some leaner, more natural dialogue, this movie could have been a bona fide classic.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact