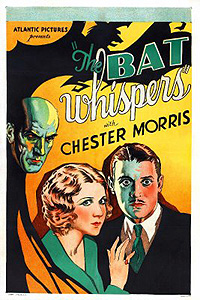

The Bat Whispers (1930) **½

The Bat Whispers (1930) **½

1930 marks one of the key dividing lines in the history of motion pictures. That was the year which the studios that made up the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors Association (the forerunner of today’s MPAA) agreed would sound the death-knell of the silent cinema; as of 1930, it would be nothing but talkies from then on. The rationale behind the decision was a simple one, and as usual, money was the determining factor. The advent of sound complicated the business of exhibiting movies every bit as much as it complicated making them, and the owners of many smaller and less profitable theaters staunchly resisted investing in the expensive new equipment that would enable them to screen the talkies. Most filmmakers, on the other hand, were very excited about the possibilities inherent in the new technology, and were eager to try their hands at using it. The problem, as far as the studio heads were concerned, was that the recalcitrance of the exhibitors was going to make it extremely difficult to indulge the creative types while still turning a profit. Eventually, somebody got the bright idea to force the theater owners to upgrade by cutting off their supply of new product that could be shown using the old equipment, and because all the major studios were in the same predicament, it proved easy enough to get all of them onboard for the interdict against shooting new silents. One immediate and possibly unintended consequence of the decision was what might have been the most concentrated frenzy of remaking yet seen, as every studio in Hollywood scrambled to recreate their biggest hits from the last ten years, all of which were about to become obsolete.

Roland West’s The Bat Whispers is thus but a small part of a very large phenomenon. What is unusual about it is that it represents one of the few occasions on which the director of a conspicuous silent success was brought back to helm the sound remake as well. And what might be more remarkable still, it displays considerable advances over its predecessor in several respects, even if, on the whole, it doesn’t work quite as well as The Bat. While the makers of its contemporaries (The Unholy Three, for example) often tried to get away with letting the novelty of the soundtrack carry the entire film, West put great effort into building upon what he had done the first time around. His use of miniatures, already impressive in 1926, expanded tremendously, and reflected far more ambition and imagination than what had been seen in The Bat. The cinematography became much more daring as well, employing camera maneuvers which would not go into general use for decades, and which must have seemed absolutely dazzling in 1930. And though the production design overall was sadly a bit more conventional than that in the 1926 film, The Bat Whispers still came out miles ahead of the standard spooky house mystery in that department.

The new version is also a little more streamlined than the old, and is generally easier to follow. As a squad car speeds along a New York street (in a shot that features some of the best back-projection work I’ve seen in my life), the radio announces that the police have cordoned off the apartment building in which a wealthy jewel collector named Bell (Richard Tucker, from The Unholy Night and Flash Gordon) makes his home. Bell has received a letter from a seemingly unstoppable criminal who calls himself the Bat, in which the arch-thief promises to drop in at the stroke of midnight to steal the Rossmore necklace, the most valuable piece in Bell’s collection. The building is swarming with cops, and all concerned are confident that the Bat has finally stuck his neck in the noose. They’re wrong, of course. Somehow, the Bat makes it to the roof of the building unobserved, and he lowers himself down to Bell’s flat, strangles the collector, and helps himself to the Rossmore necklace, leaving behind a message to the police which basically boils down to, “Nanny nanny boo-boo, stick your head in doo-doo.” Except, you know— phrased a little more eloquently than that.

The Bat then shifts his operation north to Oakdale County, where he sets his sights on the vaults of the Oakdale Bank. But on the night he picks to rob the bank, he sees to his astonishment that somebody else (The Avenging Arrow’s S. E. Jennings) has gotten there first, and is already absconding with as much cash as one human being can comfortably carry. The Bat rappels down the wall of the bank building to his car and gives chase, but the other robber has equipped his vehicle with a smokescreen generator, and temporarily leaves the Bat behind. While his pursuer slows to a crawl to avoid running off the road in all the smoke, the bank robber pulls up to the gate of a mansion marked, “Fleming,” and lets himself in through a window into the cellar. Evidently this guy knows something about the Fleming place, too, because the next thing he does is manhandle a ladder into the laundry chute so that he can climb up into it and gain access to the network of secret passages that riddle the building’s walls. In doing so, however, he makes enough noise to attract the attention of the mansion’s tenants, Cornelia Van Gorder (Gayle Hampton) and her eternally frazzled maid, Lizzie Allen (The Vampire Bat’s Maude Eburne). The old caretaker (Spenser Charters, from The Ghost Walks and the 1935 version of The Raven) says it was ghosts that made the noises in the cellar, but the women suspect it was really that Bat character the newspapers have been fussing over so much lately. In truth, it’ll be another hour or two before the Bat comes calling at the Fleming house, but even a less flamboyant criminal stalking the place is surely trouble enough.

The bank robber isn’t the only one sneaking around the mansion making odd sounds, either. That hooting noise from the garden that has Lizzie practically jumping out of her skin is really a signal from Cornelia’s niece, Dale (Una Merkel, from The Mad Doctor of Market Street), to a young man named Brook (William Bakewell, of Radar Men from the Moon), who has evidently been hiding in the bushes for some time. Brook is Dale’s fiance, whom she hopes to pass off as a gardener. The reason for this rather peculiar scheme is that Brook works as a teller at the Oakdale bank, and he is now reckoned the prime suspect in the robbery case; somehow, he and Dale have it in their heads that the real thief has brought the money to the Fleming mansion and hidden it in a secret room which is rumored to have been added to the house sometime during the last year or so. Obviously they’re right, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how they caught on. Maybe it has something to do with Richard Fleming (Hugh Huntley, from The Phantom Creeps), the nephew of the man who owns both the mansion and the Oakdale Bank. At the very least, Dale knows Richard well enough that she feels entitled to call him surreptitiously on the phone and summon him out to the house as soon as she and Brook are safely inside. There’s also a doctor (Gustav von Seyffertitz, from The Face in the Fog and the 1935 version of She) on his way over— apparently an old friend of the Fleming family— with the aim of talking the Van Gorders and their servants into packing up and moving out. All very suspicious, if you ask me.

And speaking of suspicions, before long, a cop arrives on the scene, and Detective Lieutenant Anderson (The She-Creature’s Chester Morris, whose constantly writhing eyebrows are so distracting that they really ought to have been given credit as supporting players) quickly shows himself to regard absolutely everyone under the Fleming roof as a suspect in one crime or another— not only is he there to investigate the strange things that Cornelia and Lizzie have seen and heard, but he’s also assigned to the Bat case. But Cornelia doesn’t seem to have complete trust in Anderson, because she’s also engaged the services of a private detective named Brown (Charles Dow Clark), who comes to the door just in time to deal with the fatal shooting of Richard Fleming by persons unknown. Anderson thinks it was Dale who fired the killing shot, partly because she was apparently alone in the room with Fleming at the time, but also because he knows that she’s seeing the suspect bank teller, which would make her a rival of Fleming’s if there’s anything to Cornelia’s belief that Richard was interested in getting his hands on the stolen cash so as to pay off his looming gambling debts. Naturally, though, things are much more complicated than Anderson has guessed, and there are no fewer than four competing parties in search of the Oakdale Bank loot. None of the others, mind you, is nearly as dangerous as the Bat…

Why yes— as a matter of fact, that is Batman playing the role of the Big Bad. It was right after DC Comics bigshot Bob Kane saw The Bat Whispers that he devised the basic look for the character he hoped would energize the company’s Detective Comics series, and although the resulting pop-culture icon would switch from villain to hero somewhere between the initial inspiration and the publication of the first Batman story, the image of a black-cowled figure in a bat-wing cape haunting the concrete aeries of a Deco neo-New York is unmistakable. There are enough detail differences in the two costumes, however, to make it something of a disappointment when we finally get a good look at the Bat, and realize just how pedestrian his getup is underneath that exceedingly cool cape. I’d be very interested to hear what led West to soften up the look of his main villain for the remake— could it be that the original design was considered too horrifying by 1930, or conversely that too many viewers had been seized by fits of laughter at the size of the 1926 Bat’s ears?

Otherwise, The Bat Whispers is an extremely close reproduction of The Bat. A few of the early scenes have been reordered, and the addition of dialogue helps to clear up a few points that were left a little too vague in the original, but overall, it’s evident that West’s marching orders from the studio were to make the same movie he had four years before, but with sound this time. And the sound, alas, is where The Bat Whispers gets into trouble. One distinctive feature of the very early talkies is the absence of background music. This was a conscious move, the main idea being to further distinguish the new generation of movies from the old, in which music had been the only auditory component, and had played continuously from beginning to end. (At the same time, I’m inclined to think that the limitations of recording technology in the late 20’s and early 30’s had a bit to do with it, too— the dialogue is hard enough to understand in a lot of first-generation talkies even without a musical score to compete with it.) The experiment was not considered terribly successful, however, and background music was in wide use again by 1933. In The Bat Whispers, the moratorium on music is so complete that even the opening credits play silent, but few other films that I’ve seen were as badly in need of a score as this one. Somehow the mood never quite comes together right with nothing but the dialogue to keep our ears busy, and my consciousness of this shortcoming was only underscored by the fact that my copy of The Bat had been accompanied by an excellent Harry Manfredini-like musical track far superior to the generic classical or piano scores that often mar modern editions of silent films. The other problem the soundtrack poses for The Bat Whispers is that we can now hear Lizzie Allen speak, and with Maude Eburne giving a performance that might best be thought of as Una O’Connor to the power of Agnes Moorehead, that’s something the world absolutely did not need. Her shrill antics (reinforced by the similarly shrill antics of Charles Dow Clark as Detective Brown) play havoc with the delicate balance which West had achieved the first time out, and long stretches of The Bat Whispers are extremely hard to sit through. As long as neither of the offending characters is around, The Bat Whispers is, if anything, superior to its predecessor; unfortunately, those occasions are very rare indeed after the first act, and the film suffers for it nearly as much as the audience.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact