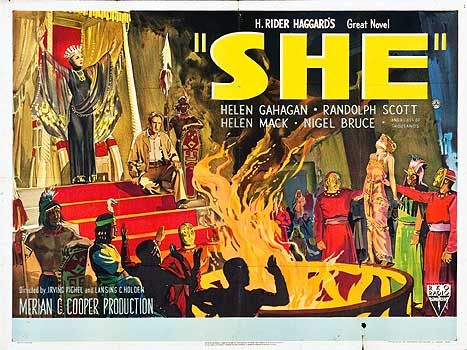

She (1935) ***

She (1935) ***

Merian C. Cooper had the Devil’s own time getting a proper follow-up to King Kong off the ground. The Son of Kong, rushed into theaters on a fraction of its predecessor’s budget, obviously just barely counted. Cooper’s final attempt— a globe-spanning Lost World epic entitled The War Eagles, developed with an eye toward release in 1938— never got beyond the pre-production phase. And in between, there was She, an exercise in frustrations as grandiose as the picture itself was intended to be. The script by Ruth Rose was a loose but readily recognizable interpretation of H. Rider Haggard’s pioneering and perennially popular fantasy adventure novel of the same name, with the setting moved north on the theory that Africa was getting played out as a venue for such stories. It expanded Haggard’s rather cozy climax to include an elaborate ritual of human sacrifice, providing an excuse for a dance number that any musical of the time would be proud to call its own. The miniatures and matte paintings of Cooper’s previous RKO-produced fantasias were to be supplemented with opulent, not to say megalomaniacal, soundstage sets. I’ve even encountered cryptic references to woolly mammoths as part of the initial program, although I’ve had no luck discovering how they would have slotted in if She had been completed according to Cooper’s original vision. And most impressive of all, She was slated for shooting in three-strip Technicolor, which would have made it one of the first live-action films to use the recently introduced process. It would have been a hell of a show, had it actually gone as planned.

The trouble started while Cooper was trying to recruit a director. James Whale, Cooper’s preferred man for the job, had commitments at Universal, while the producer’s old King Kong partner, Ernest Schoedsack, was unenthusiastic about the project. In the end, Cooper had to settle for Irving Pichel and Lansing C. Holden. Casting was a headache, too. The stars Cooper really wanted were all under contract to other studios, and he was unable to persuade those studios to lend them out. That went not only for Greta Garbo (Cooper’s pipedream first choice to play Haggard’s immortal sorceress), but even for lesser lights like Joel McCrea, whom Cooper sought on the basis of positive experience working with him on The Most Dangerous Game. But the real obstacle was the Great Depression, which still showed no sign of ending any time soon. The big Hollywood studios had been willing to accept losses during the first few years of the slump on the theory that the economy would right itself before much longer, but by 1935, it had become clear that that was wishful thinking. She was well underway, though, before the order to curtail expenses was handed down, leaving Cooper in something of a scramble. Technicolor was certainly no go. So were woolly mammoths. The colossal sets, when they appeared on film, would look strangely underpopulated most of the time, as the budget for extras contracted from “cast of thousands” levels to “cast of hundreds.” In general, the final results show a glaring mismatch between the overwhelming grandeur of those production elements that got nailed down before the funding imploded, and the rinky-dink cheesiness of those that came later. For audiences hoping to be awed the way King Kong had awed them, She couldn’t help being a disappointment, and the film lost an unbelievable $180,000 in its initial release. (To put that into perspective, 180 grand was about what Columbia or Universal would typically spend to make an entire movie in the mid-1930’s.) Only in 1949, when She was reissued on a double bill with Cooper and Schoedsack’s even more disastrously underperforming The Last Days of Pompeii, did it finally make its money back.

If, however, you come to She looking not for a spiritual successor to King Kong, but merely for un unusual spin on the well-worn trope of the lost civilization, this movie has considerably more to recommend it. We begin with ailing and elderly British scientist John Vincey (Samuel S. Hinds, from The Raven and The Ninth Guest) anxiously awaiting the arrival of his American nephew, Leo (Randolph Scott, of Supernatural and Murders in the Zoo). The reason Uncle John is ailing is because his research has given him a good case of radiation poisoning, and the reason he’s anxious is because his longtime associate, Horace Holly (Nigel Bruce, from Rebecca and Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror), is sure to need Leo’s assistance if he’s to have a chance of carrying to fruition the work that doomed the old man. It would only be fitting for Leo to lend a hand, too, since said work is a bit of a family project as it is. As John and Holly explain once Leo arrives, an ancestor of the Vinceys— also called John, and the spitting image of Leo, to judge by the centuries-old portrait hanging in the drawing room— was an incorrigible man of action. Even after he married, that previous John Vincey never settled down; he just started dragging his wife around on his adventures, too. One day about 500 years ago, the couple journeyed to Muscovy, where they ventured beyond something called the Shugal Barrier. John was never seen again, but five years later, his wife turned up in Poland, half-mad and deathly ill, raving about a flame that renders anyone exposed to it ageless and deathless— or at any rate, exempt from death by natural causes. It evidently couldn’t make John murder-proof, as subsequent events were to demonstrate. The letter Mrs. Vincey wrote to her son back home in England after her rescue has been passed down through the family from eldest son to eldest son ever since, and it came into the current John Vincey’s hands just as he was beginning to experiment with the medicinal applications of X-rays and radium. It occurred to Vincey that his ancestor’s “flame of immortality” might be the radiation from some unknown element, and he and Holly spent seventeen years trying to produce such a substance artificially. They were unsuccessful, but the nature of their failures was such as to convince them that the substance they sought could and indeed must exist. If there’s no way to synthesize it, then there’s simply nothing else to do but go looking for the natural deposit that Old John and his wife found up in Muscovy half a millennium ago. Leo is skeptical, but the implications, if his uncle is right, are too momentous to leave unexplored. He’ll take up the search, alright.

Now “Muscovy” is rather vague as directions go, but Vincey and Holly have been looking into that, too, and Holly thinks this Shugal Barrier must be somewhere in the far north of Siberia. It takes months of chasing after native legends, but eventually the search leads Leo and Holly to an Englishman called Dugmore (Lumsden Hare, from Black Moon and The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake) who claims to know where the Shugal is. Evidently it’s a cliff-ringed mountain range about as far north as there’s any point in going, and no one— not even the local Yakuts— knows what’s on the other side. The place has such a reputation for lethality that Dugmore is sure his visitors will find no native willing to go up there. Dugmore himself, on the other hand, just might— if Vincey and Holly cut him in for an equal partnership stake in whatever the prize of their venture may be. They reluctantly agree, and the next thing we know, the three men— together with Dugmore’s tough-as-nails daughter, Tanya (The Son of Kong’s Helen Mack)— are marching off to the Shugal Barrier at the head of the usual column of guides and porters.

Alas, Dugmore’s preparations just barely survive first contact with the mountains. At the top of the very first ridge, the explorers discover a dead man frozen into the face of a glacier, together with the saber-toothed cat that presumably killed him. The corpse (which closer inspection suggests to have been a servant mentioned in Mrs. Vincey’s letter) has a fortune in gold on it, and Dugmore reckons it’s never too early to get a start on nudging this venture’s account books into the black. All he accomplishes by hacking at the ice, though, is to trigger an avalanche that kills him and buries the encampment at the foot of the Shugal, leaving Leo, Holly, and Tanya with no provisions, no equipment, no shelter, and no hope of assistance. They’re forced to take refuge in a convenient cave while they ponder what to do next.

That cave is a lucky break in more ways than one. It’s lit by phosphorescence in the rocks, heated by geothermal energy, and it communicates with a cavern system that seems to run under practically the whole of the Shugal Barrier. Most importantly, that cavern system is inhabited— by two separate peoples, in point of fact! The first to make their presence felt are a stone-age tribe which will later be identified as the Amahagger. The primitives seem hospitable at first, in a severe sort of way, but Holly lets his guard down much too far by assuming that the hustle and bustle that greets their arrival in the main Amahagger settlement portends a feast of welcome on the travelers’ behalf. There is a feast in the offing, but the outsiders are to be the main course rather than the guests of honor. Leo is badly hurt in the fighting which ensues when he figures that out, and he and his companions are saved only by the intervention of the cavern’s other denizens. A man of pharonic mien (Gustav von Seyffertitz, of Sherlock Holmes and The Moonstone), who might be a tad more impressive if his wig didn’t appear to be made of acrylic yarn, rides in on a canopied litter, and the Amahagger at once prostrate themselves in cowed submission. A truly weird development transpires when Tanya attempts to convey Leo’s plight to this faux-formidable gentleman; incredibly, Dollar Store Thutmose is able to speak English! All he’ll say about it for now is that he had “a very wise teacher, who knows all the tongues of the world.” That will have to suffice until the explorers are brought before Dollar Store Thutmose’s— excuse me, Billali’s— queen, who will answer whatever of their questions she sees fit.

That queen (Helen Gahagan, a future US congresswoman and contender for Richard Nixon’s Senate seat) goes by the name Hasha Mo Tep— “She Who Must Be Obeyed”— and she sure does know how to make an entrance. Also, she takes an initially inexplicable special interest in Leo, insisting that he and he alone be brought to her private suite while accommodations are made elsewhere for Holly and Tanya. As you’ve doubtless already surmised, there’s some back-story here. That fire of immortality Vincey and the others came looking for? It’s here, in the basement, so to speak, of Hasha Mo Tep’s palace, and untold centuries ago, she used it to make her rule over this subterranean realm eternal. She was already running the show down here when the first John Vincey and his wife stumbled upon her domain, and she fell in love with the man from above. Hasha Mo Tep would have made John her prince consort, but he and his wife had other ideas. Thus it was that the immortal queen slew Vincey, and banished the woman for whom he scorned her back to the surface. All this time, however, Hasha Mo Tep has believed that John would one day return to her from beyond the grave. And now here’s a guy who looks just like him, whose companions speak the language which she has kept alive in her court as a tribute to her lost love.

Leo will hear that tale from Hasha Mo Tep herself as soon as he recovers from his injuries. Holly, meanwhile, hears enough hints of it in conversation with Billali to catch on that he and Vincey have blundered to the very doorstep of their objective. Once he and Vincey have a chance to compare notes, the scientist hatches a crafty scheme to exploit the queen’s obsession with Leo to gain access to the legendary fire. What neither conspirator plans on is the intense personal magnetism of Hasha Mo Tep, nor the insidious allure of the god-emperor lifestyle. What starts as a bid to con She Who Must Be Obeyed quickly blossoms into a genuine love affair, and not even the most unmistakable display of the queen’s casual cruelty— as when she has the Amahagger chief (Noble Johnson, from A Game of Death and The Mummy) and a score or so of his people arbitrarily executed for the tribe’s inhospitality to the Vincey party— can fully break Leo of his growing fixation upon her. The one person who might be able to do that is Tanya, who was moving tentatively toward a romance of her own with Leo before Hasha Mo Tep got in the way. Mind you, She Who Must Be Obeyed recognizes well the threat that the other girl poses, and she intends to deal decisively with it in due time.

It’s undeniably true that the budget cuts severely compromised She’s ability to accomplish its primary mission. Buying audience-wowing spectacle on the cheap requires the most careful and rigorous planning, but Merrian C. Cooper’s plans were precisely what got scuttled when RKO took away money that he was already in the process of spending. Cooper would surely have allocated his resources differently had he known from the start how limited they were going to be. Yet even there, She manages to score a few points. The Amahagger cave sets are nicely detailed and convincingly mazy, and all those kinks and twists in the tunnels go a long way toward disguising how few the troglodytes really are. Hasha Mo Tep’s underground city-state of Kor was obviously built while money was still no object, and although its colossal scale sometimes harms the movie as much as it helps, it does help a lot. (Incidentally, yes— that is the gate from the Great Wall on Skull Island redressed as the entrance to Hasha Mo Tep’s palace.) Art director Van Nest Polglase and costume designers Aline Bernstein and Harold Miles gave the people of Kor their own unique aesthetic sensibility, rather than just lazily copying the ancient Near East. There’s some impressive stunt work during the two big battle scenes, including one fire stunt that must have been outrageously dangerous given the limited technology and lax workplace-safety standards of the mid-1930’s. And Hasha Mo Tep’s final destruction by her own flame of immortality was a minor triumph of special effects artistry for its era.

All those second- and third-choice personnel acquitted themselves admirably, too. Irving Pichel may never have been more than a journeyman director, but he racked up some noteworthy credits along his march to obscurity. Pichel deserves props on this occasion simply for preventing She from being undone by its glacial pace and sedentary narrative (apparently the very factors that led Ernest Schoedsack to pass on the project). Randolph Scott displays the makings of a proper action hero, in a remarkably modern sense of the term. Admittedly he hadn’t quite come into his own yet when he starred in She, but he was lightyears ahead of the drips, clods, and nobodies I’m used to seeing in films of this vintage that weren’t designed to be sold on the strength of the romantic pairing of leading man and lady. Nigel Bruce, for his part, gives exactly the performance I’m going to wish for in vain whenever I get around to covering the later Universal Holmes films. His interpretation of Horace Holly is a bit stuffy, a bit pompous, and just the slightest bit less intelligent than he thinks he is, but he’s also courageous, competent, and even cunning when he has his guard up. Bruce is genuinely funny, too, in those scenes that put the character in a less flattering light. Helen Gahagan, while obviously no Garbo, is more than serviceable as Hasha Mo Tep— don’t let her one-role filmography fool you into expecting otherwise! She has the allure that Betty Blythe mostly lacked in the Anglo-German silent She, combined with the air of command that so eluded Ursula Andress when she played the part for Hammer Film Productions in the 60’s. The one thing I’ll say against Gahagan is that she’s maybe a little too cold and imperious for an interpretation in which She Who Must Be Obeyed isn’t an out-and-out villain. I mean, it wasn’t for nothing that Walt Disney used her performance here as the model for the evil queen in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The real delight in the cast, though, is Helen Mack as Tanya. An unapologetic throwback to the serial heroines of the 1910’s, Mack’s Tanya is equally compelling whether she’s spinning mushy fantasies of pastoral domesticity for Leo or telling off an immortal despot to her face— and the girl can handle herself in a brawl with cavemen, too. Considering Tanya’s pivotal role as the counterweight to Hasha Mo Tep, it’s essential that she be played by an actress with some spark to her, and Helen Mack has more spark than Henry Frankenstein’s laboratory.

The real secret to She’s successes, however, is probably Ruth Rose. Hers is just an extraordinarily well thought-out reworking of Haggard’s story, jettisoning exactly the parts that worked least, or that had grown most critically obsolete. Haggard’s impetus for the story never made any kind of sense. In his telling, Vincey’s mission into the domain of She Who Must Be Obeyed was a matter of family vengeance. 2000-some years before, his Greek ancestor was wronged by a Libyan sorceress, and swore her descendents to the witch’s destruction for all time; Leo’s response upon learning of this on his 21st birthday is basically, “Oh. Well, I guess I’ll get right on that, then.” Replacing that with a sci-fi quest for an unknown radioisotope puts the story on a much firmer footing. Meanwhile, although Rose’s motivation for shifting the setting was nothing nobler than Cooper’s boredom with Africa as a venue for adventure yarns, it has the salutary effect of distancing She a little from the inherent racism of the premise. At the very least, it redirects Haggard’s racist assumptions against a pair of completely fictional cultures with no clear analogues in the real world. This version of She is thus a tad more palatable to modern tastes than its predecessors and successors populated by bestial blacks, treacherous Arabs, and domineering Afro-Semites. And to return once more to Tanya, it was a shrewd move to transform Leo’s other love-interest into a Westerner, and to make her fate the pivot for the climax. Haggard’s Ustane (the nearest equivalent character) is just one more smelly foreigner so far as his Leo is concerned, but Tanya personifies everything that Leo would have to give up to become Hasha Mo Tep’s consort. Furthermore, because Hasha Mo Tep proposes to deal with the hassle her rival presents by tossing her into a volcanic vent, Tanya’s ordinary, mortal affection for Leo throws into stark relief the moral dimension of Vincey’s choice. On top of abandoning his culture, his personal background, and the entire human condition, stepping into the flame to rule at Hasha Mo Tep’s side inarguably means turning his back on his conscience and accepting the queen’s casual disdain for the value of “lesser” lives. That was always part of the deal, even in 1887 when Haggard was writing, but Ruth Rose was the first teller of this tale to see it clearly, and to give the issue the weight that it deserves.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact