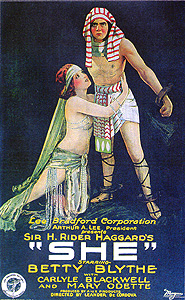

She (1925) **

She (1925) **

For all practical purposes, H. Rider Haggard is the father of the modern adventure novel. Oh, he has his antecedents, to be sure— tall tales of faraway lands are among the oldest forms of human creative endeavor— but ever since Haggard’s first novel, King Solomon’s Mines, was published in the mid-1880’s, practically every take on the themes of lost cities, lost races, and civilized men facing dreadful peril in unexplored pockets of jungle, tundra, and desert has owed at least a little something to his example. Haggard was well qualified to fill such an influential position, too, for he spent the bulk of his 20’s living in Africa, where he served as an assistant to the military governor of Natal, and like most affluent Brits of his day, his education left him conversant with ancient languages and cultures; when Haggard wrote about Africa, he was doing so as an eyewitness, and he had a firm enough grounding in the classical tradition to speculate convincingly about forgotten offshoots of Hellenistic civilization. Understandably, Haggard also left a deep imprint on the movies, whether in the form of direct adaptations of his work or in a more nebulous, inspirational mode. His fingerprints are all over the adventure serials of the 30’s and 40’s, and while his influence has waned as the sections of the map marked “Terra Incognita” have contracted, he can still be seen riding the crest of the occasional wave of nostalgia— after all, what is Indiana Jones but an American Allan Quatermain?

It is not for Quatermain and his macho spin on colonialism that Haggard is best remembered today, however, nor is King Solomon’s Mines his most widely read book. Those distinctions belong to She and its central figure, Ayesha— She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed. For that matter, She has arguably been even more widely copied than Haggard’s straight adventure novels, as it is readily adaptable to all sorts of fantastic and sci-fi-inflected settings into which a Quatermain-like character cannot so easily be transplanted. Wherever you find crumbling cities of swarthy, bestial savages, ruled over by an immortal sorceress-queen of incomparable beauty with a diabolical disregard for human life, you find a descendant of Ayesha. Everyone from respected names like Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs to the lowliest forgotten purveyor of Edwardian penny dreadfuls has riffed on She over the years, and most of them have made a decent enough living doing it. And of course, She has also been filmed over and over and over again. As early as 1899, Ayesha’s climactic accidental self-destruction in the pillar of flame which first gave her immortality was latched onto as a suitable basis for short subjects, and the American distributors of Georges Méliès’s La Danse du Feu surely had the right idea, economically speaking, when they retitled it Haggard’s She. Short versions which attempted to tell a bit more of the story (and which bore the original title) appeared in 1908, 1911, 1916, and 1917, but it wasn’t until 1925 that a proper, feature-length film adaptation was mounted. That Anglo-German production was the first (and, to date, also the last) to take an honest stab at presenting the story as Haggard wrote it, and its noticeable unevenness as cinematic entertainment may have had a thing or two to do with the progressive abandonment of the novel’s details in subsequent remakes. It might also explain the trimming down of the prints released in the US from the original 98 minutes to a much brisker 69.

Actually, even the 98-minute European running time may be truncated, either deliberately or by deterioration, because I saw the long version and it still seemed like there were some pieces missing. At “a university which, for the purposes of this romance, we shall call Cambridge” (the movie preserves the annoying 19th-century convention of coyness about names and places, even though it is completely obvious what the institution in question is supposed to be), there is a flat maintained by a graduate named Horace Holly (Heinrich George, of Metropolis), known to his friends as the Baboon, “for obvious reasons.” We are meant to infer that those obvious reasons are Holly’s great bulk, immense strength, and hirsute countenance, but if you’re asking me, a more obvious reason still is that all of Holly’s friends are assholes. One of those friends, a man named Vincey (who didn’t get his name in the credits), staggers into Holly’s parlor one evening, announces that he is terminally ill, and proceeds to saddle Holly with responsibility for his five-year-old son, Leo, whom Holly has never heard of before because Vincey himself has refused to have anything to do with the boy since his birth and the ensuing death from complications of Mrs. Vincey. You see— what did I tell you? Holly’s friends are assholes! Nevertheless, Holly accepts guardianship of Leo Vincey, and agrees to a list of bizarre stipulations regarding the child’s upbringing. Not the least of these concerns a huge, metal trunk, which is to be opened only upon Leo’s 25th birthday.

Twenty years later, Holly (whom the makeup department has aged by dyeing a bunch of gray streaks through Heinrich George’s hair) summons his butler, Job (Tom Reynolds), and the now-grown Leo (Carlyle Blackwell Sr., who appeared later on in the 1929 German version of The Hound of the Baskervilles) to see what’s inside the mysterious trunk. Among other assorted old debris, there is a letter from Vincey the Elder and a 2000-year-old potsherd inscribed with a more detailed version of the story sketched by Leo’s father. Evidently, some two millennia back, a nobleman of Hellenistic Egypt named Kallikrates (also played by Blackwell in the flashback which the reading of the potsherd triggers) went with his pregnant wife to the wilds of Libya, where they were captured by the natives and brought before their queen, who was reputed to be an undying witch. The queen fell instantly in love with Kallikrates, but he rejected her— I mean, come on… his wife was standing right there! In a rage, the queen had Kallikrates put to death, and his wife dropped off to fend for herself in the wilderness; somehow the woman survived and made it back home, at which point she swore her unborn son and all his male descendants to vengeance against the Libyan sorceress. As you might imagine, Leo Vincey is the latest of those male descendants, so the thankless revenge gig is now his. It’s the 19th century, though, and Leo is a rich Brit, so any excuse to travel to Africa and kill the natives— both animal and human— sounds like a party to him.

Vincey, Holly, and Job ship out to Libya, where they hire a guide named Mahomet (The Beetle’s Alexander Butler) to take them into the countryside. They haven’t gone far before they are captured by cavemen under the command of an old man (Jerrold Robertshaw) with a gigantic beard and a shepherd’s crook— in other words, he looks exactly like just about every cinematic representation of Moses you’ve ever seen. In the novel, the old man is called Billali, but the film never mentions his name, so for our purposes, he shall henceforth be known as Movie Moses. None of the adventurers realize this as yet, but the reason Movie Moses and the Blackface Cavemen found them so quickly is that their queen, Ayesha (Betty Blythe)— the one Leo is sworn to avenge his distant ancestor upon— has a magic kiddie pool just like the one Boris Karloff uses in The Mummy, and she saw them coming the moment they arrived at the coast. For some reason (it makes precious little sense in the novel and none at all here), Ayesha thought the incursion important enough to have the interlopers rounded up, but not important enough to tell Movie Moses what she wanted done with them. Consequently, Movie Moses must then depart alone for the lost underground city where Ayesha lives, leaving his captives in the care of the Blackface Cavemen and a girl named Ustane (Mary Odette), whom Leo Vincey accidentally marries (don’t ask…). So far as I can tell, this whole business about our heroes cooling their heels in a cave is in here solely to provide the setup for some much-needed violence. No sooner has Movie Moses departed than the Blackface Cavemen decide to eat Mahomet. The other three travelers don’t think that’s such a good idea, and a brawl breaks out; by the time the fight is over, half the tribe is dead or injured, Leo is wounded, and Ustane is trying without much success to position herself as her husband’s human shield. Luckily, it’s at precisely that moment that Movie Moses returns with instructions to bring Holly, Vincey, and Job to Ayesha.

This is where the movie itself starts cooling its heels. After Ayesha is introduced to the three Brits, not a whole lot happens until the end of the film, at least not in proportion to the remaining running time. Ayesha figures out that Vincey is descended from Kallikrates, and decides on that basis that he is indeed the reincarnation of the man she’s been pining for all throughout the last 2000 years. There is the expected conflict with Ustane, which ends with Ayesha disintegrating her rival in a remarkably paltry special effect. (Listen closely during this scene, and you’ll hear the ghost of Georges Méliès snorting, “Fucking amateurs…”) Leo Vincey falls in love with Ayesha anyway (as does Holly, for that matter— one look at her with her veil pulled back is all it takes, apparently), and allows himself to be both convinced that he is Kallikrates reborn and dissuaded from pursuing the centuries-old blood feud that brought him to Africa in the first place. He even takes the queen up on her offer to immerse him in the magical fire of immortality so that he may live as everlastingly as she does. Vincey gets cold feet at the last second, however, and the effects of Ayesha’s effort to allay his fears by stepping into the fire herself are not precisely as she intended. Evidently that fire-of-immortality business is a one-time deal…

The most conspicuous thing about She is all the dramatic posing— nay, the Dramatic Posing! Except for Heinrich George, who puts in a good, smooth, and only slightly exaggerated performance, not one of the actors here is able to convey an emotion by any means but the personal freeze-frame. They’ll mouth a line of dialogue (curiously, the dialogue pantomimes in She invariably come after the associated intertitles, rather than before as was customary in the 20’s) and then freeze the gesture that accompanies it at its most extreme and unnatural point, holding the resulting pose for several seconds at a stretch; it becomes extremely distracting after a while, and seriously bogs the movie down during what are supposed to be scenes of high emotional pitch. Further stultifying matters is the text of the intertitles. The producers were proud of the fact that Haggard wrote them himself, and put a notice to that effect in the opening credits. The trouble with this is that Haggard’s novels are as noteworthy for their lousy dialogue as they are for their pioneer status, and he hadn’t gotten any better at the dialogue game by 1925. By far the worst dialogue comes during the scene in which Leo falls for Ayesha even though she just vaporized his previous main squeeze, but it’s all pretty dreadful.

The casting in She is problematic for reasons above and beyond the performers’ highly artificial acting style, too. Heinrich George (who is absolutely perfect for the part of Horace Holly) is again the exception, but for the most part, these are not the people I’d have chosen to fill these roles. Carlysle Blackwell is as boring and ineffectual a hero as any in the annals of film, and while I suppose his casting is defensible on those very grounds (Haggard’s Leo is himself sort of an empty-headed pretty boy, and the story mostly happens to him rather than being the result of anything he does), it still doesn’t work very well. Jerrold Robertshaw may not be fully to blame for his ineffectuality as Billali, but the very fact that he looks about as convincing as a department store Santa Claus in his old-age makeup should perhaps have clued the filmmakers in that he was not the right man for the part. The biggest problem is Betty Blythe, however. Yes, she’s reasonably cute, and yes, she wasn’t afraid to do a movie in which most of her costumes consisted almost solely of veils of varying degrees of diaphany. But Ayesha is supposed to be a hell of a lot more than reasonably cute and fetchingly immodest. Ayesha is supposed to be a woman for whom men will violate their every principle, abandon all that they once held dear, and she’s supposed to be able to induce this extreme reaction simply by revealing her face. I wouldn’t buy Betty Blythe more than two drinks if she chatted me up at the bar where I hang out, and the disconnect between the mystique of Ayesha and the reality of Blythe comes close to sinking the film. Heinrich George is great, and this movie has the distinction of following the novel more closely than any version shot either before or since, but those two points really are just about all the 1925 iteration of She has going for it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact