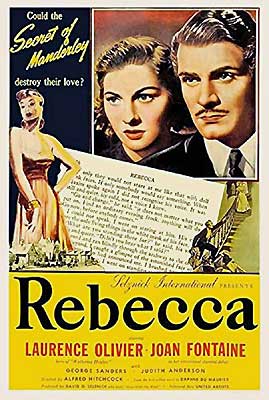

Rebecca (1940) ***

Rebecca (1940) ***

When I used to work at the public library in Crofton, we kept our mass-market paperback fiction organized by genre, since someone long ago had determined that that was how our customers related to such books. Each paperback was stamped accordingly with a letter code on the upper edge: GF for general fiction, SF for science fiction, W for Western, etc. The only code that didn’t seem intuitively obvious to me was G/R for gothic and romance. Gothic and romance? I was used to thinking of “gothic” as a subgenre of horror. What did that term have to do with flame-haired beauties being swept off their feet by roguishly virile lairds, roguishly virile Indian braves, and roguishly virile pirates (all of them bearing a striking resemblance to Fabio)? That I could simply not know that such a thing as gothic romance had ever existed should tell you something about the state of the genre in the early 1990’s, when I got that job. Apart from whoever was pretending to be V. C. Andrews that week, gothic romance was pretty well extinct in literature— and at the library, we shelved the V. C. Andrews paperbacks under Adventure/Suspense/Horror. The situation was even more dire on film. Authors of the 19th century had effectively split gothic fiction into three parallel lineages of horror, mystery, and romance in the modern sense, with the essential difference being at first a matter of emphasis. When the naïve, virginal heroine marries someone she shouldn’t, and goes to live in his ancestral castle full of sinister secrets, which are we supposed to care about most— the sinister secrets themselves, the process whereby they’re brought to light, or the titillatingly ill-advised marriage? But the horror strain quickly abandoned the traditional plotline, keeping only the settings and their implication of a world ruled by irrationality and superstition, while the romance strain spent the Victorian era scaling back the evil of the antihero love interest until he became a mere bad influence on the heroine. By the time anyone was making movies, gothic romance was too plainly about sex that Nice Girls weren’t supposed to have to stand any chance in the face of early 20th-century film censorship, and gothic stories found their way onto the screen almost solely in horror or mystery form. That changed suddenly, though, in 1940, and for about a decade and a half, gothic romance became a hot seller at the box office. The lion’s share of the credit for that short-lived reversal belongs to a single film: Rebecca.

Rebecca was a case of the right personalities and the right source material coming together to create the right time. Daphne Du Maurier’s novel was one of the biggest hits of 1938, the kind of property to make dollar signs dance before the eyes of any studio head in Hollywood. But none of those studio heads acquired the film rights. Instead, they were snapped up by rogue producer David O. Selznick. At a time when studio bosses reigned supreme, when directors were nobodies and even the biggest stars in the business were nothing but hired hands, Selznick managed to be a successful independent producer. His will was indomitable, his business savvy justly legendary, his ego colossal. If anybody could get a gothic romance past Joseph Breen and the Hays Office, he was the one. And to direct the picture, Selznick brought in a would-be throwback to the heroic age of directing, when giants like D. W. Griffith and Erich von Stroheim walked the Earth. US audiences hadn’t had much exposure to him yet, but he was taking his native Britain by storm, and Selznick was confident that Americans too would soon be talking about this Alfred Hitchcock guy. He was right, too, but the two of them were going to have to get Rebecca made first. Hitchcock was no slouch in the ego department himself, and Selznick would find himself wondering more than once if maybe the willful Englishman wasn’t more trouble than he was worth. The box office returns eventually answered that question to his satisfaction, of course.

Rebecca’s opening would become the calling card for gothic romance as a whole all throughout its brief period of cinematic prominence. In a nifty literalization of Du Maurier’s introductory chapter, it sends a subjective camera prowling about the overgrown grounds of a ruined English manor house while a voiceover by Joan Fontaine (whom our sort are most likely to know from The Devil’s Own and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea) breathlessly describes dreaming about something called Manderley. It soon becomes apparent that that was the name of the house back when it was still fit for human habitation, and that Fontaine’s character regards the place with equal parts nostalgia and loathing. Or on second thought, maybe loathing edges out nostalgia by just a little bit. It’s immediately obvious why these first few minutes proved so influential, inspiring imitation by even such unlikely films as The Devil Commands. The whole thing was shot with large-scale miniatures, enabling Hitchcock to create exactly the environment he wanted— and what he wanted was a fairy tale witch’s forest, at once picturesque and inhospitable. It’s romantic in a much darker and more Germanic sense of that term than anything you’ll find in the novel.

The transition into the story proper is thus all the more jarring, as that artificial Brothers Grimm wilderness gives way to the sun-baked sea cliffs of what will later be identified for us as Monte Carlo. There’s a man standing atop them (Laurence Olivier, from Clash of the Titans and The Seven-Per-Cent Solution), and to the girl sketching the breakers from the next crag over (that would be Fontaine), it sure does look like he’s about to hurl himself down amid the rocks and waves. She calls out to stop him, but it turns out he was just lost in thought. Not happy thoughts, mind you, but nothing worth a death-dive into the Mediterranean.

The next time we see the girl from the cliffs, she’s in the dining room of the Hotel Princesse, enduring the nonstop prattling of boorish, narcissistic gasbag Edythe Van Hopper (Florence Bates). That’s literally her job, as Mrs. Van Hopper has engaged her as a paid companion for her latest international ramble. By some measures— and certainly by the measures that Edythe prefers to use— the girl ought to be eternally grateful for this gig. After all, how often does a Proper Lady deign to tolerate the company of the Lower Orders? But by the time the waiter arrives to take the women’s lunch order, we’ll all be wondering whether she couldn’t perhaps have found a nice Magdalene Laundry to take her in instead. Mrs. Van Hopper’s companion gets a reprieve of sorts from her misery when none other than Mr. Definitely Not About to Commit Suicide walks in, and captures all of Edythe’s tiresome attention. They’ve met before, you see. The man’s name is Maxim De Winter, and he’s rather famous in English upper-crust circles. His country estate, Manderley, was for years one of the most happening party pads in the county, but all that changed when his wife, Rebecca, died. Gossip among the gentry has it that he never got over the loss. Be that as it may, Maxim makes a game effort at including his new acquaintance in the conversation as well as the old one when Edythe calls him over to their table, but without a lot of success. Mrs. Van Hopper will barely let either of her supposed interlocutors get a word in edgewise. It’s the third meeting between Maxim and Edythe’s put-upon companion that gets things really rolling, as Max catches her alone the following morning, and invites her out for a drive.

You’ll notice that I have yet to call the protagonist of this film by name. That’s because Hitchcock and Selznick have followed Du Maurier once again by refusing to give her one, so that five generations of readers and viewers have been forced to the inelegant expedient of “the Second Mrs. De Winter.” The courtship sequence touched off by their drive together reveals that handle to be as inapt as it is clunky. “The Second Mrs. De Winter” is far too heavy and impressive a cognomen for so vapid, foolish, graceless, charmless, and spineless a character as this one. Still, we have to call her something, so I propose That Silly Cow— or TSC for short. She’ll more than earn the title over the next two weeks or so, falling madly in love with Maxim even though (and perhaps actually because) he’s a moody prick who treats her almost as badly as Edythe does, and talking to him is like walking through a minefield of temper-tantrum tripwires. Maxim, meanwhile, falls just as madly in love with her, explicitly because she’s boring, weak-willed, socially inept, sexually inexperienced, and thoroughly unglamorous— that is, because she’s the polar opposite of Rebecca in every imaginable way. When Mrs. Van Hopper decides it’s time to move on from Monte Carlo to New York City, Maxim incredibly proposes marriage to That Silly Cow, and she just as incredibly takes him up on the offer.

Now that we have the ill-advised marriage, let’s go see the haunted castle. Outwardly, Manderley is quite gracious as such places go. Maxim’s staff keeps it as clean and orderly as any vacation resort, and housekeeper Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson, from Inn of the Damned and Star Trek III: The Search for Spock) runs as tight a ship as any martinet captain at sea. Nor is the tranquility of Manderley intruded upon by anything as gauche as a ghost or an attic baby. And yet Manderley is haunted just the same. It’s Rebecca, you see. Everything in the house remains exactly as she left it, and not one centimeter out of place. The rhythms of life at Manderley are those that she established, and everybody— Frith the butler (Edward Fielding, of The Man in Half Moon Street and Sherlock Holmes), Robert the… whatever you call a butler’s sidekick (Philip Winter), and Mrs. Danvers most of all— expects That Silly Cow to adopt them wholesale, right down to Rebecca’s neurotic obsession with dictating which sauces the kitchen serves up at dinner. Furthermore, everyone That Silly Cow meets seems to be comparing her to Rebecca, and deciding that they liked the first Mrs. De Winter better. For instance, TSC’s introduction to Max’s sister, Beatrice Lacy (Gladys Cooper, from The Sorrows of Satan and The Black Cat), and brother-in-law, Major Giles Lacy (Nigel Bruce, from Bwana Devil and The Hound of the Baskervilles), comes when she walks in on them discussing rumors that Giles heard to the effect that Maxim had married a chorus girl overseas. Even Max’s lawyer, Frank Crawley (Reginald Denny, of Sherlock Holmes and Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror), who seems basically to like That Silly Cow, can’t stop himself from mooning over Rebecca’s memory in front of her. And Mrs. Danvers… well, Mrs. Danvers is worth a paragraph all her own.

Mrs. Danvers loved Rebecca. Indeed, it eventually becomes apparent that Mrs. Danvers had a full-on Sapphic letch for her. And while there’s no indication that her feelings were requited, the two women could certainly bond over stereotypical lesbian man-hating, since Rebecca was in the habit of acquiring and using up boyfriends on the side the way other careless rich people acquire and use up fast cars. Danny (as Rebecca called her) used to end most of her evenings combing her mistress’s hair while she lounged about in a transparent negligee, the two of them laughing together like malicious schoolgirls over Rebecca’s latest hapless conquest. So it’s bad enough, as far as Mrs. Danvers is concerned, that Max has gone and remarried. It’s worse that he has replaced her beloved, evil-hearted mistress with someone who actually cares about making him happy, impossible though that may be. And to replace her with this simpering, low-born nonentity? No. No, do you hear? Mrs. Danvers is not going to stand for that!

Of course, nobody’s going to tell That Silly Cow any of the things she’d need to know in order to navigate this maze of obscure expectations and hidden agendas successfully, and she therefore gets forced into detective mode despite both her desires and her inclinations. The irresistible impetus comes from a pair of random encounters. First, TSC stumbles upon the swankly appointed cottage on the beach where Rebecca used to entertain her beaus, and meets there a harmless little loony called Ben (Leonard Carey). She doesn’t grasp the significance at the time, but Ben’s ramblings point to a question which That Silly Cow has not yet thought to ask— how exactly did Rebecca die?— and when she does finally ask it, they’ll also hint at a truth more sinister than the boating accident that is the official explanation. Then That Silly Cow has a run-in with one of Rebecca’s boyfriends, a smarmy creep by the name of Jack Favell (George Sanders, from Doomwatch and Hangover Square). Their conversation is her first hint that Maxim’s previous marriage was perhaps less happy than she has assumed.

TSC’s snooping doesn’t get very far, though, before she plausibly decides that Mrs. Danvers is the more pressing concern. Also plausibly, she figures that the best way to thwart the treacherous housekeeper is to begin acting more like Rebecca— or at any rate, more like the idealized Rebecca of her insecure imagination. With that in mind, That Silly Cow dives headlong into the deep end, and suggests to her husband that they revive the dormant Manderley tradition of the annual masquerade. She’ll organize the whole thing, just like Rebecca used to, and they’ll put Manderley back on the social map of the county. It sounds like a decent enough plan on its face, but That Silly Cow has seriously underestimated Mrs. Danvers. This is the housekeeper’s own arena that TSC is stepping into, and she’s setting herself up for the landed gentry’s idea of a Carrie-scale social humiliation. But as it happens, Mrs. Danvers’s figurative bucket of pig’s blood may be the least of anyone’s worries on the night of the masquerade. While the party at Manderley proceeds toward its sour conclusion, a swimmer from the nearby village chances upon the long-lost wreck of the boat on which Rebecca died. And when Colonel Julyan the local magistrate (C. Aubrey Smith, of And Then There Were None and Transatlantic Tunnel) gets a look at that wreck, he’s going to have a lot of uncomfortable questions for Maxim De Winter.

I’m sure you’ve all guessed by now what I found the great stumbling block to enjoying Rebecca. I simply cannot buy the central relationship as a thing to be rooted for, except insofar as it takes both Maxim and That Silly Cow out of circulation, and stops them from spoiling the happiness of anyone who actually deserves better. And believe it or not, the movie sands some of the rough edges off of both characters in an effort to make them more likeable! For example, this telling omits the moment from Du Maurier’s that turned me permanently and irrevocably against the narrator (at a time when she and Maxim aren’t even really courting yet, she vandalizes a prized possession of his, simply because it bears another woman’s— that is, Rebecca’s— signature), and dials way back on the neurotic bullshit until life at Manderley gives TSC a reason to be constantly second-guessing herself and jumping at her own shadow. And on Maxim’s side, the film turns a clear case of second-degree murder into something more like involuntary manslaughter. Since the changes don’t suffice to make either character sympathetic, it might have been better to leave them as they were, and to embrace That Silly Cow’s status as a fool who wants things that are bad for her.

What’s weird is that Rebecca still mostly works despite the great, gaping chasm at its center. There was a lot of sparring between Hitchcock and Selznick over how this movie should be handled, and interesting stuff frequently arose from the sparks of their clashing. The tone keeps toggling between sappy Hollywood love story and dark European fable, often at unexpected times or in counterintuitive directions. Selznick seems to have held in check Hitchcock’s tendency toward visual overindulgence, perhaps by diverting the director’s surplus creativity into efforts to outmaneuver him. And when the two men did see eye to eye, like on the subject of slipping shit past the censors, they achieved very impressive things together. Rebecca gets away with an astounding amount of sexual impropriety, simply by starting with the character who commits most of it already dead. Can’t get much more decisive an in-story punishment for sin than that, can you? What’s more, this movie is shockingly close to explicit about Mrs. Danvers’s lesbianism, and it’s hard to imagine how Selznick could have defended the housekeeper’s blaze-of-glory exit against the Production Code’s ironclad ban on suicide as a means of resolving conflicts.

In the final assessment, though, what makes Rebecca so memorable and effective in spite of its faults is simply that this is the movie with Mrs. Danvers in it. I don’t have the necessary background in Victorian gothic fiction to be certain that Daphne Du Maurier’s evil housekeeper is as original to the genre as I suspect, but I can tell you this much: in all the gothic fiction I’ve read from before the split into horror, romance, and mystery sub-lineages, or within the romance strain after the split, the principal villain was always male— until Rebecca. After Rebecca, however, it’s lady monsters out the wazoo, reaching their apotheosis in Flowers in the Attic’s diabolical grandmother. The nearest thing I can find to an antecedent to Mrs. Danvers is Miss Havisham in Great Expectations, a book which I’m not comfortable counting as a gothic of any stripe (although Dickens surely did borrow from the genre’s conventions in writing it). Like Miss Havisham, Mrs. Danvers has let herself be consumed by a dead past in which she is determined to dwell forever. But the forms taken by the two women’s respective obsessions are very different, as are the targets toward which they aim the associated resentments. In a way, you might think of Mrs. Danvers as a riff on the old faked-up haunting trope, insofar as she’s the one keeping the malign memory of Rebecca alive. The “ghost” of Manderley is her creation, just as surely as if she were in the habit of spending her nights dressed up in a phosphorescent sheet, clanking chains and moaning. Her enmity toward That Silly Cow is also a fresh interpretation of a genre standby, for it makes an interesting muddle of the usual gothic class subtext. Instead of the wicked aristocrats I’m accustomed to, Rebecca posits a wicked servant— albeit one who has fully internalized an aristocratic value system. And as if the original characterization weren’t, well, original enough, Hitchcock and Selznick have made their Mrs. Danvers an even more distinctive figure by shaving a decade or two off of her age and putting a sexual spin on her toxic devotion to her dead mistress. There was nobody else quite like this in the field of gothic villainy in 1940, and despite a fair amount of imitation in the years since then, Mrs. Danvers is still pretty much in a class by herself.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable on haunted, cursed, possessed, or otherwise evil locations. Click the link below to tour the rest of this neighborhood of the damned.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact