Sherlock Holmes (1916) **½

Sherlock Holmes (1916) **½

I’m going to say it again: there has never been a better time to be a fan of old or peculiar movies. It’s a matter of access, really. Today’s unprecedented combination of technological dissemination, demographic change, and pop-culture fragmentation has made it easier than ever to see stuff that we might only have read about and pined for in previous years. Cable TV and home video were transformative enough all by themselves, but the miniscule per-unit production cost of DVDs has opened the floodgates by making practically anything potentially profitable to release. Meanwhile, the pairing of inexpensive video editing software with the internet has rigged it so that as long as there are enterprising bootleggers in the world, there need no longer be any such thing as “out of print.” New patterns of immigration have brought formerly little-known Third World cinema traditions to the attention of watchful fans in the West. And most importantly, the extinction of popular monoculture has given rise to a situation in which anything can be deemed worthy of respectful, curatorial treatment. If it’s out there to be had, rest assured that someone will take a shot at circulating it to whatever niche market can be found, in the best presentation that economics will permit. Remarkably, that goes even for things that were once believed not to be out there. The past 20 years or so have witnessed a remarkable expansion of efforts to track down lost movies, surpassing anything I’m aware of in that direction from the preceding century, and those efforts have enjoyed an equally remarkable success. In the time since I began writing these reviews, I’ve lost track of all the important and/or interesting films that have turned up, intact or in pieces, after decades of total unavailability. And it always gives me a charge to cover one of the hitherto-lost, even when it’s a real turkey. Naturally, I enjoy it all the more when the newly unearthed picture is decent or better.

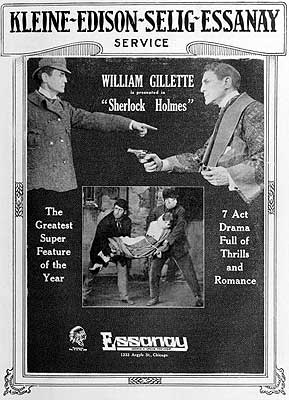

The 1916 Sherlock Holmes is happily a case of the latter. I’ve had occasion to mention this movie before, in the context of its 1922 remake, but I never guessed that I’d get a chance to deal with it in its own right, let alone after a delay of only six years. The later version, you see, was itself rescued from the lost list, so what were the odds that this one had survived too? The significance of this Sherlock Holmes is twofold. To begin with, it was the first feature-length film about Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous super-sleuth, although the character had previously appeared in the odd one-reeler here and there. But more importantly, Sherlock Holmes was not merely adapted from William Gillette’s long-running stage play of the same name, but starred Gillette himself in the title role. That name won’t mean much to the casual fan today, but 100 years ago, nobody save Doyle himself was more closely associated with Holmes in the public mind. Gillette would perform his play more than 1300 times, becoming the founding member of the club that more famously includes Arthur Wontner, Basil Rathbone, and Jeremy Brett. The 1916 Sherlock Holmes is Gillette’s only known appearance on film, however, and thus the only opportunity for posterity to see the first definitive portrayer of the character in action.

Unlike the remake, which wastes oodles of time on Holmes and Watson as college students, and disastrously detours into a meeting between the detective and Professor Moriarty at the very beginning of the former’s career, this version cuts right to the chase. Alice Faulkner (Marjorie Kay) is being held against her will at the remote country villa of James and Madge Larabee (Mario Majeroni and Grace Reals). That’s because Alice has in her possession correspondence detailing the love affair between her sister and the heir to a minor European principality, and the Larabees are hoping to use those letters to blackmail the young man’s father, the Count von Stalburg (Ludwig Kreiss). The affair ended badly, you see, and the girl was so distraught over it that she killed herself. Naturally, that makes Alice no friend of the Stalburgs, but she’s also no criminal. Thus the kidnapping and captivity designed to force from her the location of the letters— the Larabees figure that somebody should profit from the count’s vulnerability, and if Alice won’t do it, it might as well be them.

Alice is proving a very tough nut to crack, though, and what’s more, Count von Stalburg has hired the famous consulting detective Sherlock Holmes (Gillette, as we’ve already established) to find the Faulkner girl and persuade her to relinquish the incriminating letters. Going a few rounds with Holmes convinces the would-be blackmailers that they’re outmatched, so they call in a consultant of their own. That would be Moriarty (The Raven’s Ernest Maupain). Luckily for Alice, however, Holmes has allies of his own. In addition to his inseparable companion, Dr. Watson (Edward Fielding, later of Dead Man’s Eyes and Flesh and Fantasy), the detective can also rely on a courageous rapscallion named Billy (Burford Hampden) and even the Larabees’ own servants (Stewart Robbins and Leona Ball), who have come to sympathize with Alice’s plight.

William Gillette took substantial liberties with Sherlock Holmes, but he did so with Arthur Conan Doyle’s blessing. By 1896, when Gillette was working on the script for his play, Doyle was thoroughly sick of his most famous creation, and was in no mood to quibble over continuity or characterization. “You may marry him, murder him, or do anything you like to him,” Doyle responded by telegram to Gillette’s admission that he was planning to invent a love interest for Holmes. It should follow, then, that the movies based on that play would go in some curious directions as well. Overall, I find the 1916 film more successful in exploring those departures from the form than the one from 1922. If the romance between Holmes and Alice feels both rushed and forced, it is at least rendered basically plausible by good casting and Gillette’s decision to play down the hero’s eccentricity. Weird as it feels to see Watson reduced to a mere vestigial appendage, it’s justified by the greater practical utility of Billy, Forman, and Therese within the context of this story. Most significantly, the 1916 Sherlock Holmes makes probably the cleverest use of Moriarty that I’ve ever seen. Instead of being simply Holmes’s nemesis, this Moriarty is explicitly his antithesis. More than just a criminal mastermind, he’s the guy whom other criminals call for backup when their capers are in danger of flying off the rails, just as people come to Holmes when they have a problem beyond the competencies of official law enforcement. And like Holmes, the present incarnation of Moriarty seems to do what he does mainly because he enjoys the intellectual challenge of it (although the money is obviously pretty nice too). Even the diminution of the expected Holmes-Watson relationship ends up serving the doppelganger theme by putting Watson more or less on par with Moriarty’s henchman, Bassick. Purists are likely to be annoyed, but I don’t have half enough invested the character to be one of those.

Sadly, Sherlock Holmes affords us only a heavily compromised basis on which to evaluate Gillette’s interpretation of the part. That was pretty much inevitable, though, given the absence of spoken dialogue. What we can say is that Gillette serves up an unexpectedly naturalistic rendition of an unexpectedly normal Holmes, especially in comparison to the twitchy weirdo portrayed by John Barrymore six years later. Gillette’s Holmes is also notable for how much time he spends actually detecting things, instead of simply deducing or intuiting them from tiny clues observed on the fly at an improbable distance. Obviously we can’t have a proper Sherlock Holmes without some of the latter, but it’s refreshing to see him have to work for the solution to a problem too, you know? I’m not as pleased with how this movie handles the interaction between Gillette’s Holmes and Edward Fielding’s Watson— which is mostly to say that there’s barely any interaction in the first place. Gillette does display some halfway decent chemistry with Marjorie Kay, though, which is probably more important under the circumstances. I don’t really buy Holmes and Alice becoming a full-fledged couple as part of the happily-ever-after, but at least it’s no stretch to imagine that they like each other. Again I point you to the Barrymore version for an illustration by contrast. Besides, the loving doesn’t really matter until the final curtain, whereas the liking is critical to the part of Holmes’s mission that involves convincing Alice to lay aside her grudge against the Stalburg family.

The starkest superiority of this Sherlock Holmes over the remake, however, is a matter of story structure and balance. Having neither seen nor read the original stage play, I can’t be certain whether it contained the long prologue seen in the Barrymore version concerning the characters’ college years, the formative encounter between the young Holmes and Moriarty, or the tedious soap opera concerning the count’s son and the dead Faulkner girl. What I can say is that the last feature is the only item on the list that this movie is not clearly better off without. Beginning with Alice already in the Larabees’ clutches creates a sense of immediate urgency which the remake sorely lacks, and cuts down on narrative clutter— a significant consideration in a silent film. On the downside, this Sherlock Holmes is a little too oblique when it comes to what happened between Alice’s sister and her noble lover. I’m not sure I’d have been able to follow the first act at all without the remake’s more detailed treatment of the issue underlying Alice’s captivity to guide me. Still, there’s no question but that the elder Sherlock Holmes invests its surprisingly long running time (almost two hours!) much more wisely and productively than the younger. Current cinematic trends toward dithering and over-explaining have heightened my appreciation for efficiency to an almost monomaniacal degree, so it should be no surprise that this is the version I prefer.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact