Bwana Devil (1952) **

Bwana Devil (1952) **

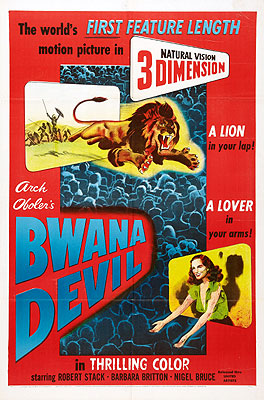

Generally, I don’t bother with old-school jungle adventure movies. The genre as a whole just doesn’t interest me. I’m going to make an exception, though, in the case of Bwana Devil because of the tremendous significance of this all-but-forgotten film in the history of exploitation cinema as a whole. Bwana Devil, as the more erudite of you may already know, was the first feature-length movie ever shot in 3-D. Given the great importance of idiotic gimmicks in the marketing of exploitation movies of all genres over the years, I think it ought to be pretty obvious what a milestone this movie becomes on the strength of that pioneer status. And so, just this once, I’m setting aside my prejudice against jungle movies to bring it to your attention.

Bwana Devil’s plot is very similar to that of the recent Ghost in the Darkness, and concerns the havoc wreaked on the efforts of engineer Robert Hayward (Robert Stack, best known for his role as Eliot Ness on “The Untouchables,” though if you were as big a dork as I was in the mid-1980’s, you might also remember that he was one of the voice-actors for Transformers: The Movie) to build a railway across central Africa when some of the local wildlife takes it upon itself to reintegrate Hayward’s workers into the food chain. Hayward begins the movie as the number-two man on the project, working under the supervision of Major Parkhurst (Ramsay Hill, from Panther Girl of the Congo and When Worlds Collide), a stuffy executive type from the home office of the construction firm owned by Hayward’s father in law. The trans-Africa railway project is sort of a last chance at glory for Hayward, whose previous engineering efforts back home have mostly not turned out as planned— the implication is that his heavy drinking may have had a little bit to do with that. But thus far, his current job has been rather smooth sailing, though it is progressing a bit slowly for Parkhurst’s taste.

Then one day, the laborers Hayward shipped in from India lose all interest in their jobs. Parkhurst and the engineer quickly discover that rumors of a killer lion have been circulating among the men, who understandably contend (in the words of the foreman) that “their contract didn’t say anything about man-eating lions.” But Parkhurst (self-important, stiff-upper-lip fucker that he is) doesn’t believe a word of it. In fact, it is Parkhurst’s opinion that Hayward himself started the rumors in the hope of getting the job called off so that he could finally go home to his wife Alice (who will be played by Barbara Britton when at last we meet her). The boss-man is forced to reconsider his position, though, when workers start disappearing, only to show up later as mangled, half-eaten carcasses stashed in the underbrush around the campsite. And Parkhurst himself ends up on the lion’s menu when he leaves camp for the nearest city without checking first to see whether or not the steam engine he’d been using to shuttle himself back and forth had enough fuel for the journey.

With Parkhurst dead, Hayward is now in charge, and suddenly he isn’t so eager to go home anymore. Now that the entire responsibility for the railway is on his shoulders, his determination to get the thing built has been renewed, while the contest against the lion has begun taking on the proportions of a full-on vendetta. However, neither Hayward nor his staff doctor Angus McLean (Nigel Bruce, most famous for his many portrayals of Dr. Watson in the long-running Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes series, though he was also in the 1935 version of She), accomplished hunters though they are, can catch the murderous beast. So Hayward does the sensible thing, and calls in the heavy hitters— the warriors from the nearby Maasai village, for whom killing a lion is a major rite of passage. He and Angus go along for the ride while the hunters do their stuff, and thus they have front-row seats when the Maasai warriors get the biggest, nastiest shock of their lives. Just when they have the lion surrounded, and are closing in for the kill, a second, bigger, meaner lion appears and attacks them from behind. The two lions take advantage of the confusion caused by this ambush, and thoroughly rout the Maasai. Looks like it’s back to the old drawing board for Hayward.

But the worst is yet to come. When the team of expert big-game hunters Hayward calls in from England arrives, it turns out they’ve brought Alice along with them. Sure, Hayward’s glad to be reunited with his wife after all these months, but he understandably thinks that a construction site under siege from anthropophagous felines is no place to bring a lady. And if that’s true, it’s even less of a place to bring a small child, like the three-year-old son of one of the hunters’ servants. Well, if you thought the Maasai got their asses handed to them, just wait ‘til you see what happens to the Great White Hunters. On the very night of their arrival, while they’re all staying up late playing poker with Angus and getting hammered on gin, the lions sneak into the campsite, walk right into the Pullman cars the hunters are using as their living quarters, and kill every single last one of them, including Angus and the little boy’s parents.

Of course you realize this means war. And while Hayward is busy figuring out how he’s going to fight that war, fate steps in to answer that question for him. Alice, who has been filling in for the dead servants in taking care of the boy, turns her back on him for just a moment, allowing the kid a chance to run off into the bush to chase after some small animal or other. Hayward’s hand is forced— with a three-year-old running loose in lion country, he’s got no choice but to get his rifle and head on out, hoping for the best. Alice, too, feels compelled to join the hunt; after all, it was her carelessness that caused the situation in the first place. And believe it or not, this climactic hunt actually has a surprise or two in store.

In every respect but one, Bwana Devil is a most unimpressive movie (although the lion-attack scenes are uniformly hilarious). Robert Stack demonstrates throughout that even when he was younger, he was better suited to voicing cartoon robots and introducing true-crime dramatizations than he was to anything that required him to really act. The supporting characters are, for the most part, rather hard to swallow, and the Great White Hunters (who are mainly played for laughs) are especially irritating. The story also has some plausibility problems (what are the odds that lions would have the strategic acumen to stage a feline Pearl Harbor on a Pullman car full of drunk hunters?), moves at an excessively slow pace, and is rendered needlessly confusing by incompetent editing. But director Arch Oboler did do one thing right here. Even in the 2-D TV print, it is obvious that a tremendous amount of thought went into how best to take advantage of the 3-D cinematography. There are very few “hey, look at this— it’s in 3-D” moments in Bwana Devil, and all but one of them makes good narrative sense, rather than coming across as an ill-considered cheap shot. (The Haywards’ 3-D kiss is the conspicuous exception.) Instead, Oboler uses the 3-D process to give depth to nearly every frame of the film. A hunting scene early in the movie offers a striking example. Hayward is in the foreground of the shot with his rifle, while several tree branches are visible only a few feet in front of the camera. Suddenly, one of the Indian laborers appears from behind the underbrush some 30 yards behind Hayward to tell him he’s found the body of the camp’s missing cook. As Hayward turns and runs off after the Indian, a monkey clambers out onto one of the tree limbs above the engineer’s head. It’s a beautifully composed scene, and it must have been really spectacular in 3-D. What impresses me the most about Oboler’s technique is that such thoughtful, sophisticated composition should appear in the very first 3-D feature. Most directors of 3-D films used the effect to create gaudy, unnecessary set-pieces (have a look at House of Wax or the more recent Parasite for examples of what I’m talking about), or employed it as a marketing device only (for instance, there is very little in Creature from the Black Lagoon or Revenge of the Creature that benefits much from being seen in 3-D). Even 30 years later, during the short-lived 3-D revival of the early 80’s, there wasn’t one movie made that displayed the kind of intuitive understanding of how 3-D could be used to enhance the film as a whole that Oboler demonstrated here. It’s enough to make me hope that somewhere, in the forgotten depths of the B-movie abyss, another Arch Oboler 3-D flick awaits discovery— one in which he was given a more sensible script and a decent cast.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact