Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) ***Ĺ

Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954) ***Ĺ

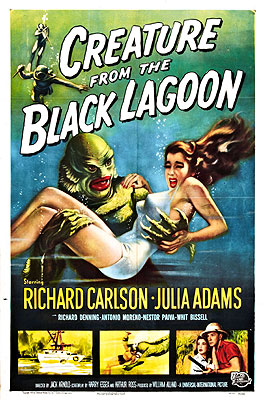

You know, when you really sit down and think about it, itís awfully hard to invent a completely new monster. We humans have been dreaming the things up for untold thousands of years now, and at this late stage of the game, we seem to have all the bases pretty much covered. But once in a while, someone will come along and show us that it is still possible. Harry Essex, Arthur Roth, and Jack Arnold pulled it off in 1954 with Creature from the Black Lagoon, one of the very best monster movies of the 1950ís. The breed of monster that made its debut here was, of course, the gill-man, a beast which, though it may lack the high cultural visibility and the archetypal resonance of the vampire or the lycanthrope, continues to put in the occasional appearance even today.

It sometimes seems as though the filmmakers of the 1950ís recognized only three possible origins for their monsters. If they didnít arrive on the scene in a flying saucer, they were either spawned as by-products of ill-considered applications of atomic power, or they were holdovers from prehistory-- creatures that time forgot, in the parlance of the day. That the original gill-man falls into the last category becomes clear in Creature from the Black Lagoonís first scene, when a paleontologist named Dr. Carl Maia (Antonio Moreno, a Spanish actor whose motion-picture career stretches all the way back to 1912!) uncovers the fossil of a partially mummified hand that, though generally humanoid in appearance, possesses unmistakable webbing between its wickedly clawed fingers. Thrilled at his discovery, Maia leaves the site of the dig (somewhere in the Amazon basin) and returns to his supporting institution to try to secure backing for an ambitious expansion of his expedition. His boss, Dr. Mark Williams (Richard Denning, from The Day the World Ended and The Black Scorpion), is all for the idea; if Maia succeeds, Williams hopes to parlay that success into an unprecedented fundraising windfall. In fact, Williams himself agrees to return to the Amazon with Maia; the rest of Maiaís new team consists of marine biologist Dr. David Reed (Richard Carlson, of It Came from Outer Space and The Valley of Gwangi), a promising grad student named Kay Lawrence (Julie Adams, who would show up many years later in the hair-metal horror flick Black Roses), and a fourth scientist by the name of Edwin Thompson (Whit Bissell, who played the mad doctors in both I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein).

The team hires a boat called the Rita, under the command of a Venezuelan skipper named Lucas (Nestor Paiva, from Tarantula and Jesse James Meets Frankensteinís Daughter), and heads off down the Amazon. Unfortunately, there is no sign of the rest of the fossil gill-man in the limestone deposit where Maia found the hand earlier, and even more unfortunately, something has killed the hired laborers Maia left to guard the site of the excavation. Lucas thinks maybe it was a jaguar, but weíd know better even if we hadnít been privy to the laborersí death-scene, and thus hadnít seen them strangled and lacerated by something with webbed hands. After arrangements are made for dealing with the dead men, Dr. Reed suggests that erosion may have carried away part of the limestone embankment, and thus deposited the rest of the fossil along the river-bed. When Lucas informs the scientists that the branch of the river on which the fossil hand had been found terminates in a small lagoon deep in the jungle, Williams seizes upon Reedís idea as one that may yet salvage the operation., and the team sails further downstream to find this lagoon, despite the misgivings of just about everyone but Williams.

I hope youíve all grasped the fundamental concept thatís about to come into play here, but in case you havenít, Iím going to spell it out for you: in monster movies, the moneyman is always wrong. And while Williams may also be a scientist, his role as the principal fund-raiser for his institution makes him a moneyman first and foremost. So of course his decision to take the team downriver to the lagoon is going to get some people killed. The lagoon looks idyllic enough at first, and its raw primitiveness re-ignites the scientistsí interest in what they came to do-- itís easy to believe youíll find fantastic relics from the prehistoric past in a place like this. Reed and Williams donít find any fossils on their initial sweep of the lagoonís bottom, but they do discover lots of limestone from the embankment upriver. And when Kay goes for a swim a bit later, she finds something even more interesting-- or more to the point, something even more interesting finds her. I am referring, obviously, to the famous scene in which the camera follows the young woman from beneath the water while the gill-man swims along with her only a few feet below, belly-up in order to get the best possible view of her in what might be the worldís most notorious white one-piece bathing suit. Kay never realizes the gill-man is there (though she does notice that something touches her ankle a couple of times), but her recreational interlude is soon to bring doom from the depths to threaten her and her colleagues.

First the gill-man attacks the scientists when they go fossil-hunting a second time. Most of us would decide it was time to go home at that point, but Williams goes all Carl Denham on us when he sees the creature, and gets it into his head that what his institution really needs is the worldís last gill-man, stuffed and mounted in a big glass case. That would bring in the dough, let me tell you! Reed agrees that they should try to catch the gill-man, but he is adamant that it must under no circumstances be killed. Their attempts to catch the beast, either alive or dead, meet with only temporary success, and the creature kills a member of Lucasís crew while escaping. At this point, Williamsís colleagues have had enough. They want to leave the lagoon and come back with a bigger, better-equipped expedition that will be properly prepared to handle a large, dangerous animal. Williams still wonít hear of it, but the Rita is Lucasís boat, as the captain and his bowie knife remind the glory-hungry scientist, so Lucas will be the one to decide when the team goes home. But Lucas is only half right. It may be his boat, but all decisions regarding when it will leave the lagoon will be made by the gill-man. There is, you see, only one way out of the Black Lagoon, and while no one was watching, the gill-man dragged a big-ass fallen tree over to block the exit. The Rita isnít going anywhere, at least not until the gill-man has taken possession of Kay.

It takes the thing a couple of tries, and heíll have to go through several of the men to do it, but the man-fish ultimately succeeds in shanghaiing his quarry back to the underwater cave he uses as his lair. Itís a good thing for Kay that the cave has a second entrance from the shore, and itís an even better thing for her that the gill-manís skin, though heavily enough armored to be impervious to spear guns, is not also bulletproof. Note, however, that Reed stops his armed posse from finishing the creature off. The last shot of the film certainly makes it look like the monster is dead, but the ending remains sufficiently ambiguous to leave open the possibility of a sequel. Jack Arnold clearly believed he was on to a good thing here.

He was right. Creature from the Black Lagoon delivers just about anything you could ask for from an old-fashioned monster movie. Though he would drop the ball rather spectacularly with Revenge of the Creature, and later on with Tarantula, Arnoldís technique meshes almost perfectly with this movieís script. His pacing is smooth and steady, and even brisk by 50ís standards, while his handling of the numerous underwater scenes-- usually the worst, most lifeless segment of any movie-- is little short of revelatory. Arnold is also well-served by his actors, who do much to make their admittedly flat and stereotypical characters believable. Richard Carlson, Richard Denning, and Julie Adams in particular manage to imply far more complexity in their relationships to each other than the script presents on its face. And of course, let us not forget the monster. The gill-man is a wonder to behold. He is easily the classiest 50ís movie monster, a model of tasteful restraint in comparison to, say, the Metaluna Mutant of This Island Earth, and a paragon of workmanship in comparison to the creature costumes of, for example, Paul Blaisdel (The Day the World Ended, The She-Creature, It Conquered the World, Invasion of the Saucer Men, et cetera ad infinitum). Not only that, the gill-man is even fairly believable from an anatomical/physiological perspective, a rarity so spectacular in the world of monster movies that one must wonder what mysterious interplay of cosmic forces was at work the week it was designed. Add in the fact that, more than 45 years ago, someone was able to put together a foam latex monster suit so supple that Olympic swimmer Ricou Browning could perform in it underwater with all the natural grace of a creature born and bred beneath the waves, and this triumph of special effects artistry becomes even more amazing.

But I think the most remarkable thing about Creature from the Black Lagoon is the way a single film etched in stone the conventions of what would become an entire subgenre. Not only do subsequent gill-men bear the expected close physical resemblance to this one, they also share his motivations-- they kill men, but lust after women. Naturally, in the 50ís and 60ís, nobody was willing or able to tackle this subject head-on, but itís still perfectly obvious what is going on. Why else would the Creature from the Black Lagoon kidnap Kay and spirit her away to his hideout, which just happens to be equipped with a few patches of dry land-- useless to the creature himself, but awfully convenient for his air-breathing hostage? As in King Kong, which famously deals with an equally impractical inter-species crush, the issue of why never comes up. After all, to address that question explicitly would require an equally explicit admission of the monsterís hard-on for human women, and no such film could have gotten made while the Hays Code was still in force. Such things would have to wait for the 1970ís to take the wrecking ball to all previously agreed-upon standards of taste and propriety. And even then, it would take Roger Corman, non-porn Hollywoodís sleaziest producer, to make a movie that dealt directly with what Creature from the Black Lagoon and its progeny had only implied.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact