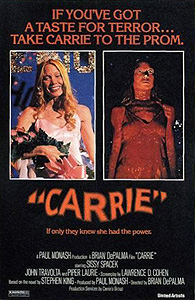

Carrie (1976) ***

Carrie (1976) ***

Carrie was Stephen King’s first published novel (although not the first one he wrote to see publication— two of the books which appeared later under his pseudonymous Richard Bachman byline predated it, at least in draft form). It was also the first of his books to be optioned for the screen, and Brian DePalma’s film version is thus interesting for being the only Stephen King movie to appear before its author became a one-man cottage industry and the poster boy for the 70’s and 80’s revival of the market for horror fiction. It is also one of the few King adaptations made by a director of note, and one of the very few to have received any respect at all from anybody. In fact, I am of the opinion that Carrie has garnered considerably more respect than it actually deserves, and that its reputation is nearly as inflated as that of the plagiaristic show-off responsible for it. That still places it comfortably within the 95th percentile for Stephen King movies, however.

DePalma begins with a pair of scenes which together prove that really obtrusive directorial technique can indeed work once in a while. First, a gaudy aerial tracking shot of a bunch of girls playing volleyball on an outdoor asphalt court gradually zeroes in on seventeen-year-old Carrie White (Sissy Spacek, who fled the horror genre like her ass was on fire after Carrie, not returning until The Ring Two and An American Haunting nearly 30 years later), just in time to catch a player on the opposing team shouting, “Hit it to Carrie— she always blows it!” Carrie blows it with as much panache as ever I did in high school gym class, earning herself the opprobrium of all the other girls on her team. Then we are unexpectedly treated to a scene that could almost have come from a Radley Metzger film, as the camera slowly and dreamily pans across the locker room, with nude and semi-nude girls floating in slow motion through dense clouds of shower steam. This jarring foray into eroticism is really the feint for a sucker-punch that comes when Carrie, soaping herself up in the shower, experiences the onset of what turns out— incredibly— to be her first-ever period. Even more incredibly, Carrie’s upbringing has been so cloistered that she is unaware even of the existence of the human menstrual cycle, and she flies into a panic, believing that she has suffered some sort of horrible uterine hemorrhage. Her classmates are slightly less than understanding. In fact, the other girls proceed to pelt the hapless Carrie with tampons and maxi-pads, chanting “Plug it up! Plug it up! Plug it up!” all the while. Only when Miss Collins the gym teacher (Betty Buckley) comes to investigate the ruckus does Carrie get a reprieve from her torment. It takes a while, but the seemingly impossible vastness of Carrie’s ignorance about her body finally dawns on Collins, and she escorts Carrie to the principal’s office for a dismissal slip after helping her clean herself up and telling her what’s what. The most important aspect of the incident has gone almost unnoticed amid all the chaos, however. As Carrie’s terror and shame and panic reached their peak, the bulb in the nearest overhead lighting fixture shattered explosively.

You might wonder how it’s possible for a girl to make it to the age of seventeen in America in the late 20th century without absorbing at least some knowledge of menstruation— Miss Collins certainly does. The simplest answer is that in Carrie’s world, it isn’t the late 20th century at all. Indeed, the late 13th is probably more like it. Carrie’s mother (Piper Laurie, from Ruby and The Faculty) is both a religious fanatic and not fully sane. As we discover when Carrie returns home, it is Margaret White’s belief that menstruation is a manifestation not of adulthood, but of sin— a curse visited by God upon women who have impure desires and lustful thoughts. Consequently, far from being consoled, Carrie is punished when she gets back to the house, locked in a dingy closet with a hideous statue of a leering and gore-streaked St. Sebastian and made to pray for divine forgiveness until suppertime. One gets the feeling Carrie has spent a significant fraction of her life locked in that closet over the years.

Meanwhile, Miss Collins visits a curse of her own upon the girls who mobbed Carrie in the shower. She lobbied hard for a three-day suspension for all offenders, backed up with the revocation of their tickets to the senior prom, but the principal thought that was too draconian. So instead, Carrie’s classmates have been sentenced to a week’s detention— the catch being that Collins herself will oversee that detention, meaning that the girls might as well be spending their afternoons in boot camp for the next week. And if anyone decides to skip out on detention, then it’s a three-day suspension and the forfeiture of prom tickets. Of the other girls, only Chris Hargensen (Nancy Allen, of Dressed to Kill and RoboCop) attempts to fight the stiff sentence. I believe Sonny Curtis had a thing or two to say about such endeavors…

Sue Snell (Amy Irving, from The Fury and The Turn of the Screw) has a totally different reaction from Chris. She gets that what she did was wrong, and she proves herself truly exceptional among teenage girls by looking for a way to make it up to Carrie. Sue eventually settles upon the rather bizarre notion of having her boyfriend, varsity sports hero Tony Ross (William Katt, later of House and Cyborg 3: The Recycler), ask Carrie to the prom in her stead. Tony initially balks, Carrie rejects the overture even after it has been made, and the whole strange business leads Miss Collins to suspect that Sue is merely setting Carrie up, but the girl’s heart really is in the right place, and a suitable application of pressure at several points down the line eventually makes the Snell Plan for Personal Atonement a reality.

Gossip to the effect that Tony Ross will be going to the prom with Carrie White rapidly permeates the school, and the story eventually finds its way to Chris Hargensen. The notion of Bates High School’s universal scapegoat ever getting a chance to rise above her appointed station incenses Chris, and she soon devises a wowser of a scheme to put Carrie back in her place. Chris has a boyfriend too, after all, and Billy Nolan (a pre-Saturday Night Fever John Travolta, who somehow manages to project even less dignity here than in Battlefield Earth or The Devil’s Rain) holds a position among the grease-monkey bad boys roughly equivalent to that of Tony Ross among the jocks. She also has a willing agent on the prom committee, in the form of her best friend, Norma (P. J. Soles, from Rock ‘n’ Roll High School and The Devil’s Rejects). In an intrigue that would have won an approving nod from John Cantacuzenus, Chris enlists Billy and his reprobate friends to procure her a bucket of pig’s blood, which she then orders hidden on one of the overhead girders above the stage where the king and queen of the prom will be crowned. Norma, meanwhile, is to falsify the vote count for the coronation, ensuring that Tony and Carrie will wind up on that stage. At the crucial moment, Chris will then pull a rope attached to the bucket of blood from her hiding place beneath the platform, turning Carrie’s moment of glory into the biggest, most revolting humiliation of her put-upon life. What Chris has not figured on is the ramifications of that exploding lightbulb in the locker room on the Day of the Flying Tampons. The onset of Carrie’s menses was accompanied by the awakening of her latent telekinetic powers, powers which she has been determinedly honing ever since. Carrie’s newfound abilities have made her one very dangerous girl, and Chris, with her spiteful and vicious prank, is fixing to pull the cork on a lifetime’s worth of bottled-up rage.

The big difficulty with Carrie is that the meat of the story consists of a single calamitous incident toward which all of the otherwise unrelated plot-threads inexorably lead. With no foreknowledge of the doom overhanging everybody, it would appear that the story is mostly just spinning its wheels. Stephen King got around the problem by imagining how the outside world would respond to the apocalyptic events of prom night, and liberally sprinkling the novel with excerpts from the proceedings of a government task force convened to study the case, and with quotations from survivors’ memoirs and journalistic exposés. He makes it clear from the very first page that something unbelievably awful is going to happen before all is said and done, and that very few of his characters are going to make it out alive. The first draft of Lawrence D. Cohen’s screenplay apparently reproduced King’s inelegant but effective conceit, but Brian DePalma didn’t want to do it that way. Instead, he took a strictly chronological approach to the story, with the result that Carrie the movie suffers from a distinct shortage of direction. He attempts to make up for this shortcoming with bravura camerawork and loads of wry wit, but his efforts are never entirely successful. His seemingly reflexive cribbing from Hitchcock (including even a reucrring musical sting lifted from the Psycho shower scene!) is especially counterproductive. Meanwhile, there was no way the budget offered by United Artists would cover the epic outpouring of violence that brought the novel to a close (in the book, Carrie comes very close to wiping the town of Chamberlain, Maine, right off the map), so a significantly more modest climax was in order. Even setting aside the silly nightmare sequence at the very end, the film’s conclusion comes as something of a letdown after all that waiting around for something to happen.

The acting also leaves a bit to be desired. Sissy Spacek mostly does well with the puzzlingly underwritten title role, and Amy Irving and Nancy Allen both have their moments, but those three somewhat uneven performances are as good as it gets. Piper Laurie completely misunderstood both her part and the movie as a whole, assuming that anything featuring such an over-the-top character as Margaret White couldn’t possibly be meant entirely seriously, and she spends the whole film teetering on the brink of high camp. Laurie’s intermittent stabs at mimicking Spacek’s sleepy Southern drawl (one would expect a mother to have the same accent as her daughter, after all) never come anywhere close to working, either. Betty Buckley is just plain miscast as Miss Collins, and the less that is said about John Travolta and William Katt, the better.

What keeps Carrie from falling apart is DePalma’s understanding that the novel was, at bottom, a jaundiced examination of the social snake-pit that is the modern American high school. To a great extent, this is a story about adolescent girls making life hell for each other for no better reason than that that’s how things have been done since time immemorial, and the ill-fated efforts of two girls in particular to make an end-run around the system. Sue Snell tries to opt out by making a conspicuous show of benevolence toward the person at the absolute bottom of the high school pecking order, while Carrie uses her paranormal powers to tear down the whole edifice of her victimization. In that context, it’s interesting that the two boys have been reduced here to almost totally passive agents of their girlfriends’ wills. Tony Ross was sort of a well-meaning doofus in the book, too, but he did at least seem to have some capacity for independent thought. Billy Nolan, on the other hand, has been completely reinvented. King portrayed him as a genuinely dangerous thug, willing to be manipulated by Chris, but only to a very limited extent, and only so long as what he received in exchange seemed more valuable than a little surplus pride. By the time prom night rolls around, Chris has lost whatever control over him she had, and he turns on her like a mad dog. The cinematic Billy Nolan could never pose a threat to anybody except by driving drunk, and Travolta’s occasional attempts to play tough just make Nolan look like an even bigger buffoon. The plot against Carrie remains Hargensen’s game from beginning to end. Carrie is at its best when DePalma is playing with this material drawn from adolescent life: in the wanton cruelty of the tampon-tossing scene, in Chris’s spoiled-bitch rebellion against Miss Collins’s detention regime, in Carrie’s bitter suspicion of Tony’s motives when he asks her to the prom. Ultimately, high school is thoroughly suffused with its own brand of horror, and by trading on that, DePalma makes up for a lot of his missteps in handling the more overt horrors of a girl with a bomb in her brain.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact