The Turn of the Screw (1989) **½

The Turn of the Screw (1989) **½

Now that I’ve seen all four of the made-for-cable mini-movies comprising “Shelley Duval’s Nightmare Classics,” what most strikes me about the whole enterprise is how fearlessly revisionist it was. Although the series title might be taken to herald a fusty reverence for the source material, every single installment took remarkable liberties of plot, characterization, theme, and emphasis with the old stories they adapted. It didn’t always work, to be sure, but the successes were generally worth the failures on an episode-by-episode basis, and some of the changes wrought by the various screenwriters were downright inspired. The Turn of the Screw might be the most unabashedly faithless of the bunch, in ways that put me in something of a quandary. On the one hand, Henry James’s short novel of the same name is easily my least favorite classic horror tale of the 19th century, so I ought to be more amenable than most to seeing it defaced and disfigured almost beyond recognition as it is here. And I certainly can’t deny that some of the things that writers James M. Miller and Robert Hutchinson, along with director Graeme Clifford, have done to it are aimed directly at the qualities that most annoy me about The Turn of the Screw in the original author’s telling. Just the same, though, I think this version might go a little too far toward some of the opposite extremes, while simultaneously retaining aspects of the novel that don’t fit at all with the adaptors’ innovations.

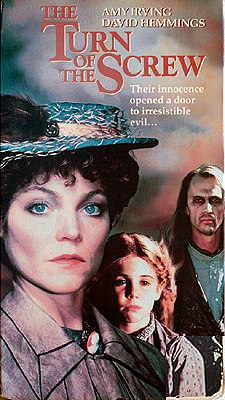

A young lady— and make no mistake, this gal is a lady— whose name we never will learn (Amy Irving, from Hide and Seek and Carrie), having fallen on hard times, answers a want ad placed by a notorious upper-class wastrel called Harley (David Hemmings, of Beyond Erotica and Barbarella). Harley has a niece and a nephew living at Bly, the family’s country estate, which came into his possession upon the deaths of his brother and sister-in-law some years ago. Parenting the two children himself would severely impinge upon his busy schedule of gambling, boozing, and womanizing, so he has need of someone with the good character he so manifestly lacks to bring them up on his behalf. Interestingly, it seems that what really decides Harley in favor of the present applicant for the position is her scandalized rebuff of his advances when he takes her out to discuss her prospective duties over dinner. It’s worth noting, however, that although Our Heroine resists Harley’s blandishments, she evidently does so more out of concern for propriety than from lack of interest. This is a woman who doesn’t like to be damp in the drawers, rather than one who is simply impervious to erotic stimuli.

Mr. Harley’s new governess will find her defenses sorely tested at Bly. The boss’s preferences in art run to the frankly salacious, so that there’s scarcely a painting or sculpture in the house that doesn’t depict a nude woman somehow or other. The books in his library are similarly smutty by Victorian standards, although I’m sure they contain little to shock a 21st-century reader’s sensibilities on that score. Most disquieting of all to Our Heroine, the children whom she’s charged with overseeing are distinctly earthy for scions of privilege. Flora (Irina Cashen), perhaps six or seven years old, has the kind of imagination that has always disturbed the conservative temperament, drawn to unladylike topics such as pirates and shipwrecks. Her older brother, Miles (Balthazar Getty, from Lord of the Flies and Habitat), promises to be even more of a handful. In his early teens, Miles is acutely conscious of his status as the future master of Bly, and he has cultivated precociously adult tastes for spirited horses and strong whiskey while retaining his childish ones for war games, affectionate roughhousing with Flora, and gallivanting all over the manor grounds in defiance of considerations like rain showers and suppertime. He’s the kind of kid who can turn even a history lesson into an uncomfortable experience for the governess, as he expounds enthusiastically on William the Conqueror’s illegitimate birth and propensity for siring bastards of his own. Nevertheless, Our Heroine takes an immediate liking to both her charges, much as she took a liking to their charming scoundrel of an uncle earlier.

The new governess does not take a liking to the man (Michael Harris, of Satan’s Princess and Slumber Party Massacre III) whom she spies prowling about on Bly’s rooftop terrace, however. Indeed, the gaunt, lank-haired stranger gives her the absolute heebie-jeebies. At first she makes the plausible assumption that John the groundskeeper (Olaf Pooley, from Naked Evil and The Gamma People) has taken on an assistant, but when she goes to chide him for doing so without warning her that she’d be seeing an unfamiliar face about, the old handyman avers somewhat defiantly that he can still do the work of maintaining Bly without help— except, of course, at the height of the summer growing season. The question of the prowler’s identity becomes more urgent when he appears again, this time peering in through the windows of the study while the governess is writing her letters, only to vanish without a trace when she rushes out to confront him. As it happens, Mrs. Grose the housekeeper (Micole Mercurio, of What Lies Beneath and Alligator) knows a fellow answering the stranger’s description. He sounds like a former employee of Mr. Harley’s called Peter Quint. Quint was a real piece of work, embodying the peasant versions of all Harley’s numerous vices, and possessing a nasty violent streak into the bargain. He carried on an indecently indiscreet affair with the Harley children’s former governess, too— a girl by the name of Jessel— which ended with her pregnant out of wedlock. But if that’s who the governess’s mystery man really is, then the residents of Bly are in serious trouble indeed, because Peter Quint is dead. He went to the gallows for murder, condemned largely on the strength of Harley’s testimony as a character witness. Poor Miss Jessel, still in love with Quint despite everything, hurled herself from the rooftop terrace in despair when she heard the news. And that means we can be pretty sure whom we’re dealing with a day or two later, when a phantom woman (Cameron Milzer, of Cherry 2000 and Chopper Chicks in Zombie Town) starts haunting Bly as well.

The revelation of that sinister angle on Bly’s history leads the governess to make some connections that had escaped her notice before. Although she naturally found it upsetting and sad whenever Miles or Flora would let slip their hostile, resentful feelings for their neglectful, reprobate uncle, it puts an entirely new light on the situation to consider that their upbringing had previously been entrusted to an all-too-corruptible hussy in thrall to a depraved killer. What if the attitudes and behavior that the current governess finds so unbecoming in kids of their station reflect not merely a lack of moral instruction, but a deliberate miseducation in the opposite? Now that that grim possibility has occurred to her, Our Heroine seems to see signs of it everywhere— and especially in the discomfitingly amorous tone that Miles begins taking in his one-on-one interactions with her. It’s enough to make her change her mind about Bly and the whole Harley family, and she writes her boss a letter of resignation the very morning after she first hears Miles speak to her in an unfamiliar adult voice which she takes to be that of Peter Quint.

Letters take time to reach their addressees, however, even with a postal service as enviably efficient as Victorian England’s. By the time Harley arrives to see for himself what the hell is happening at Bly, the embattled governess has reversed herself once more. Not only does she now intend to stay on after all, but she proposes to wage all-out spiritual war against Bly’s degenerate ghosts! You can imagine how the exceedingly worldly Harley takes that news. Coming hot on the heels of the discovery that the new governess has hidden all of his nude paintings and statuary away in the attic, hearing her appoint herself God’s ghost-buster on the children’s behalf is enough to convince him that this bitch is fucking crazy. Harley fires her on the spot. The thing is, though, that Our Heroine has a theory about what Quint might be up to with his return from the grave, and if she’s right, then Harley is in as much danger as Miles and Flora, albeit of a rather different sort.

Whatever I think of their take on The Turn of the Screw as a whole, I have to admire the nerve of James M. Miller and Robert Hutchinson in turning this most obnoxiously prim of all ghost stories into a tale of spectral possession and supernatural revenge. And I might admire even more the screenwriters’ elevation of Henry James’s sub-Dickensian “let that be a lesson to you!” ending to the level of Full 70’s Bummer. I can’t deny, however, that if Peter Quint has an explicit agenda, let alone an agenda of hounding the Harley family to Hell in retaliation for getting him hanged, then this is just barely The Turn of the Screw anymore. Furthermore, it might represent an even more fundamental distortion of the original tale to make the uncle the ghosts’ true target, and the children merely the instruments whereby Quint and Jessel mean to attack him. At the very least, the latter change transforms the pair’s defining traits— their sexual misbehavior and disregard for propriety— into a strange sort of red herring, because those are the very things the wicked ghosts and their mortal foe can agree on.

Precisely because the sex stuff is just misdirection now, it’s bizarre, too, that the filmmakers have so heightened the governess’s venereal neuroses. From the moment when her job interview with Harley threatens to turn amorous, they present her, and Amy Irving deftly plays her, as a woman whose outspoken prudery is a carefully maintained defense mechanism against the prurience in her own nature that she doesn’t want to face. Meanwhile, by advancing Miles’s age from the upper single digits to the early teens, Clifford and company substantially alter the impact of the boy’s awkward, stumbling attempts to play the man in his dealings with the governess. These interpretations of the characters would be perfect for an adaptation that openly embraced the fashionable critical reading of The Turn of the Screw in which the haunting is either innocuous or downright imaginary, and the real problem at Bly lies in the protagonist’s unacknowledged obsessions. Again, though, that isn’t this Turn of the Screw at all. I suspect we’re looking at a misaimed attempt at polyphony here, but that too belongs in a substantially different take on the story. As in the original novella, the psychological framing simply can’t survive contact with the definitively supernatural. And although this internal discrepancy is merely puzzling for most of the movie’s length, it turns destructive in the end, when the terms of the showdown over Miles between ghosts and governess seem to endorse out of nowhere the latter’s worldview, which the filmmakers had treated with unmistakable skepticism up to then. If the boy is at genuine risk of becoming Quint’s new host-body, then it seems to me we’ve gone beyond anything that ought be resolvable by symbolically taking a fireplace poker to his uncle’s collection of big-titty Neoclassical girls.

One department in which The Turn of the Screw gets everything absolutely right, though, is the casting and performances. Impressively, this is true even despite the incoherency at the film’s core, for each actor perfectly plays the stipulated version of their part, even if the parts don’t fit together right as written. Amy Irving equally projects both the governess’s strident disapproval of practically everything and the salivating inner need which that disapproval exists to repress. Michael Harris is splendidly domineering as Peter Quint, cutting a fearsome figure even with barely any dialogue— and none at all in ghostly form. Cameron Milzer is less riveting as Miss Jessel, but given how little screen time she gets, it might be even more noteworthy how fully she conveys the impression of a submissive besotted by the baddest of bad boys. Even Micole Mercurio does sound yeoman work as Mrs. Grose, seeming sharp enough to manage a humongous Victorian estate, but nevertheless so instinctively trusting in the perspicacity of her “betters” that she’ll roll right over and believe the governess about anything, at least until Harley steps in to give her a stern reality check.

But the MVPs, as they seem to be in any decent version of The Turn of the Screw, are the two kids. Mind you, Balthazar Getty and Irina Cashen will never be mistaken for Martin Stephens and Pamela Franklyn of The Innocents, but that isn’t what they’re aiming for anyway. This version of Flora is defined by the vividness of her imagination, together with her unerring instinct for using it in ways that needle the governess’s sense of decorum, and Cashen’s contribution is a blunt guilelessness that feels authentically like a little kid just blurting out whatever’s on her mind. She’s great, in her artless way, even if she most likely arrived at her precociously astute portrayal just through sheer lack of acting experience. As for Getty, his Miles is nothing but guile, suggesting a much more conscious and deliberate form of manipulation and deceit than Stephens played 28 years before. This is a Miles much further along the road to what the governess would consider corruption, and crucially, it’s very close to explicit that his admiration of Peter Quint stemmed from the two of them regarding Harley as a sort of common enemy, even before Quint’s execution. It therefore stands to reason that Miles would be the most exploitable target of opportunity for the revenant’s revenge, and Getty’s best trick is his ability to toggle between the playfulness of the child he only recently stopped being and the disturbingly adult steely chill that comes over him whenever Miles has occasion to discuss his uncle. You don’t have to share the protagonist’s prim attitudes to be disquieted by those swings of affect, and while there’s plenty about The Turn of the Screw that doesn’t quite work, you can’t justly say that about Balthazar Getty’s performance.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact