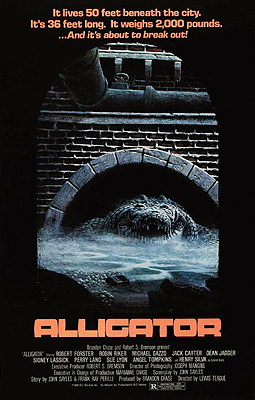

Alligator (1980) ***

Alligator (1980) ***

A funny thing happened in and around New York City between 1927 and 1938 or thereabouts. Once or twice every year or two during that period, somebody would find an alligator where no such animal had any business being. They’d turn up in ponds, in rivers, in storm drains and sewer lines. Most of the time, they weren’t very impressive as alligators go (although an eight-footer was reportedly dragged from a Harlem manhole and beaten to death with shovels by a pack of teenagers led by one Salvatore Condoluci in the winter of 1935), but the mere fact of any subtropical swamp-critter setting up shop in a Northern city was too weird not to attract attention. Where were the errant beasties coming from? What could an alligator find to eat in the city’s sewers and storm drains? How could a non-hibernating reptile survive the rigors of a New York winter? And what about all the Escherichia coli? That shit’s even deadlier to gators than it is to us, so how on Earth could they survive for any length of time literally swimming in human feces? The answer, of course, was that they didn’t manage any of those feats, not really. In all of greater New York’s confirmed 20’s and 30’s gator sightings, the animals were eventually traced at least tentatively to some human who had recently lost theirs— a naturalist passing through town with his specimens, a steamer laden with exotic wildlife accidentally dropping some of its cargo overboard in the harbor, some rich fool getting careless with his private menagerie, that sort of thing.

But then in 1959, Robert Daley published The World Beneath the City, his history and popular mechanics exposé on the labyrinth of subterranean public works that enables New York— and by extension all other large American cities— to function. One of Daley’s sources was Teddy May, a colorful character who served as New York’s Superintendent of Sewers for over 30 years, retiring in 1954 or 1955. May told Daley that it wasn’t just Sal Condoluci and his friends who had gator trouble in 1935. According to May, his own sewer workers began badgering him with tales of run-ins with reptiles, until eventually he agreed to go downstairs and see for himself. What May supposedly saw on that trip amounted to whole colonies of alligators, living in the branch lines where the current was no stronger than a gentle stream. Naturally the city couldn’t have that, so May instituted a program of extermination, directing his men to poison, trap, club, or shoot any gators they came across as circumstances permitted, until finally it was safe for them to go down into the sewers again. It was a gripping account, and Daley saw no reason to doubt it at the time. The thing is, though, that there doesn’t seem to be any corroborating evidence that it ever happened. No office memos, no invoices or receipts for equipment, no contemporary newspaper reports on the extermination effort, nothing. Furthermore, those who knew him personally remembered Teddy May as a lover of tall tales, including tall tales about himself. So maybe the reason May’s gator-killing initiative left no paper trail is because that “colony” he saw consisted of three or four juvenile animals, and marshalling the resources to wipe them out entailed a single afternoon’s work.

Whatever the truth of the situation, The World Beneath the City transformed a historical curiosity twenty years forgotten into one of the most persistent of America’s urban legends. Forget about methane gas, rat packs, and E. coli; the real reason to leave sewer spelunking for the professionals of your local municipal water works was all the goddamned alligators! And it wasn’t just New York anymore, either. By the time I was around to hear the stories, the sewer gators had acquired an origin that could place them underneath any city in the country. You see, one of the stupider things that Floridians and their Gulf Coast neighbors did before the advent of the Endangered Species Act was to capture baby alligators to sell as pets to even dumber tourists. It probably didn’t happen nearly as often as legend would have it, but you still had to ask, what became of all those patently unsuitable pets once they grew big enough for their patent unsuitability to manifest itself? The truth is almost certainly boring: it’s extremely difficult to keep baby reptiles alive outside their natural habitats. But for those who don’t know about all the ills that little gators are prey to, the obvious assumption is that an impulsively acquired alligator that had outgrown its welcome as a pet would soon find itself flushed down the toilet or tossed into the nearest storm drain.

Then along came Jaws, and with it an irresistible incentive to press any and every sufficiently dangerous animal into service as a movie monster. Grizzly bears, wild dogs, piranhas, barracudas, killer whales, giant cephalopods, you name it. By the time alligators got their turn— and frankly, I’m surprised that it took five years— the original model had been worked over so many times that it had lost most of its luster. A gator eating campers in the Everglades would have been old hat, but a sewer gator… That had potential. Still, Frank Ray Perilli, who wrote the earliest draft of the script that became Alligator, thought it needed even more of a gimmick. Perilli’s instincts ran to broad comedy anyway, so he envisioned a Jaws parody in which a Milwaukee sewer gator would grow to prodigious size after consuming a vat of contaminated beer. Having seen a few other movies that Perilli wrote, I’d say we dodged a bullet when John Sayles got the job of script-doctoring Alligator, and decided to toss Perilli’s draft straight into the trash can. The Alligator we actually got is nearer in both tone and quality to Sayles’s earlier Piranha, which is to say that it’s an exciting monster movie with a sense of humor, but never quite crosses the line into comedy.

In the summer of 1968, the Kendall family took a road-trip vacation to Florida. The part that thirteen-ish Marisa Kendall (Leslie Brown) would later remember most clearly was a visit to a Seminole reservation, where the main attraction was alligator wrestling. That day, one of the alligators won! And who knows? Maybe seeing the gator-wrestler get his leg mangled below the knee contributed to the sudden fascination that caused Marisa to pester her parents until they bought her an alligator hatchling from the Indian swamp-hermit who was selling them out of a stand erected in the parking lot. Marisa didn’t get to keep Ramon (as she dubbed the little reptile) for very long, however. Only a few days after returning home to what I take to be the Missouri side of Kansas City, her father threw a temper tantrum that ended with the baby gator being flushed down the toilet.

Twelve years later, in the same city where the Kendalls lived, homicide detective David Madison (Robert Forster, from The Darker Side of Terror and Uncle Sam) is working a pair of unusual cases. One concerns the death of sewer worker Edward Norton, pieces of whom were fished out of a filtration tank at the city’s main water treatment plant this morning. The other concerns a spate of apparent dognappings, in which some of the missing animals have later turned up— again in the municipal sewage filters— disemboweled, and with their vocal cords cut. The dognappings are a little outside of Madison’s usual line, but (1) the common method of body disposal might imply a common perpetrator as well, and (2) Madison has a personal interest, since one of the vanished dogs belonged to him. Much to the displeasure of the local press (Daily Probe reporter Peter Kemp [20 Million Miles to Earth’s Bart Braverman] especially), the detective seems to be having more success so far with the dogs.

What’s really going on there is that a scientist in the employ of Slade Pharmaceuticals by the name of Helms (James Ingersoll, of The Man with the Power and The Naked Cage) is paying a crooked pet shop owner called Gutchell (Sydney Lassick, from Sinderella and the Golden Bra and The Unseen) to supply him with experimental subjects, and Gutchell has gone Burke and Hare on him. Helms injects the stolen dogs with some kind of hormonal preparation (resulting, in at least one case, in a Lhasa Apso the size of a Labrador retriever), vivisects them, and hands the leftovers back to Gutchell, who disposes of them in the sewer. Madison doesn’t know any of that, but the questions he’s been asking both Helms and Gutchell lately are enough to convince them that he’s starting to see at least some of the picture.

It looks like a serious lead in both cases, then, when Gutchell is the next person to wash up piecemeal in a sewage filtration tank. Madison takes an eager young uniformed cop named Kelly (Perry Lang, of Teen Lust and The Hearse), and descends into the sewer to see if they can find any more of Gutchell or Norton. What they find, to their horror and astonishment, is the killer himself. It’s Marisa’s long-lost pet Ramon, all grown up. And when I say “grown up,” I mean grown up. The alligator must have been eating lots of Helms’s hormone-infused dogs, because it’s more than 30 feet long now, and has an appetite to match. Kelly gets eaten, and Madison is picked up ranting incoherently about alligators outside of a manhole a while later.

Madison’s boss, Chief Clark (Fear City’s Michael V. Gazzo), has enough respect for David to humor him some, but he doesn’t, strictly speaking, believe his story. Just the same, Clark accompanies Madison to the laboratory of none other than Marisa Kendall (who has matured into Robin Riker, from The Stoneman and Body Chemistry II: The Voice of a Stranger, since last we saw her), now the foremost herpetologist in the region. (You can take the gator away from the girl, but evidently you can’t keep the girl away from the gators.) Kendall sensibly outlines all the objections to the sewer gator legend that we covered above, and points out as well that the creature Madison describes is at least twice the size of the all-time record-holder for the species. She doesn’t want to call David a liar, but she just can’t see any way for his story to be true.

There is one person willing to listen to Madison’s gator tale, once he finesses it out of the nurses who treated David during his brief hospitalization for shock, and that’s Peter Kemp. Mind you, Ramon eats him, too, when he goes into the sewers himself to follow up, but not before Kemp captures his killer in about half a roll of 35mm photographs. The bits of Kemp that find their way into the filtration tanks include his camera, and once the contents are developed and examined, Madison no longer looks like half the putz that Clark, Kemp, Kendall, and most of the other men on the force took him for. The trouble is, he soon makes himself look like an even bigger putz by botching an operation designed to drive the alligator out of the sewers and into a SWAT team killing box outside one of the big storm drains along the river levees. That creates an opportunity for the eponymous owner of Slade Pharmaceuticals (Dean Jagger, from End of the World and X: The Unknown) to cover his tracks, which the detective was getting far too close to finding. Slade leans on the mayor (Jack Carter, of Heartbeeps and The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler) to get Madison fired, and to entrust the hunt for the gator to an outside contractor. That would be Colonel Brock (Henry Silva, from Black Noon and Megaforce), an arrogant big-game hunter who clearly doesn’t begin to understand what he’s about to take on. Worse still, Madison’s little stunt with the SWAT team seems to have convinced Ramon that the sewers aren’t safe for him anymore. Soon the monster gator is running loose above ground, and no pond, creek, canal, swimming pool, or golf course water hazard can be trusted not to become his next temporary lair. Fortunately neither David Madison nor Marisa Kendall is the sort to be deterred by an official statement that their services are not wanted.

I’ve never been able to convince myself permanently that Alligator wasn’t directed by Joe Dante for release through New World Pictures. I mean, it was neither of those things, but it feels so much like the work of both that director and that studio that I must always consciously remind myself who was really behind it. Lewis Teague and Group 1 International should probably take that as a sidelong compliment. Although Alligator isn’t quite on par with Piranha and The Howling, that’s the company in which it rightly belongs. Like those movies, it’s witty and smartly scripted, it strikes a deft balance between dark humor and full-throated exploitation horror, it features a capable cast effectively employed, and it even slips in some surprisingly pointed social commentary here and there. Robert Forster’s charmingly world-weary David Madison and Henry Silva’s impenetrably smug Colonel Brock are both fun to be around, and the running gag about the detective’s deteriorating head of hair gets funnier the longer and more insistently it runs. Marisa Kendall, meanwhile, is the sort of heroine we could use more of: good at her job, ready and able to take matters into her own hands, willing to admit a mistake, and not constantly in need of rescue. What’s more, she’s that rarest of cinematic creatures, a female scientist motivated not by some past trauma, but by longstanding intellectual interest. The film’s readiness to crack a joke at the slightest provocation doesn’t get in the way of it being occasionally downright nasty, as when a group of children playing pirates at a nighttime costume party inadvertently get one of their number killed by making him “walk the plank” off a swimming pool diving board and into the waiting jaws of the unseen Ramon. That scene is also a fair example of Teague’s knack for composing a shot in ways that build suspense, but there are some moments down in the sewers that are even better— when the sweep of a flashlight or some such thing shows us, but not the characters onscreen, that the alligator is lurking nearby. Alligator even has some unexpectedly decent special effects up its sleeve. The mechanically troublesome animatronic Ramon looks great when it’s working properly, and okay even when it isn’t, but the best shots are those in which a live alligator is let loose on a miniature set. The latter last just long enough to make the necessary impression, without giving the viewer’s eye a chance to register any weaknesses in the scenery unless one deliberately looks for them. Movies with crocodilians as the monsters have a disappointing track record, I must admit, but Alligator is among the best of the lot.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact