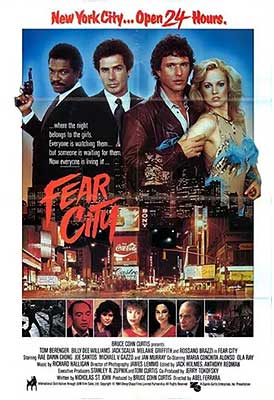

Fear City (1984) ***

Fear City (1984) ***

I remember reading once, on the Classic Horror Film Board, one of the commentators there sniffing that he didn’t consider slasher movies to be horror films at all. So far as he was concerned, they were just some weird, unpleasant strain of crime melodrama. I disagree with the gist of his position, obviously, but that guy really was on to something that doesn’t get the acknowledgement it should. Horror and crime stories share a few miles, so to speak, of frontier over near the vast, lawless swamp where they both overlap with the suspense genre, and that frontier is as porous in places as any other inter-genre boundary. For example, back in the 50’s, EC’s crime comics could be every bit as gruesome as the publisher’s more famous horror titles, and they were condemned just as strongly by Frederic Wertham and his allies because of it. Later on, in the 80’s, there was a small but noteworthy crop of films that pitted Dirty Harry-like police detectives against slasher-like serial killers, with results that defy easy categorization. And then there’s Fear City, the last of Abel Ferrara’s early movies dramatizing the urban blight of 70’s and 80’s New York. Fear City takes yet a third approach to blending the crime and horror genres, focusing less on its ineffectual cops than on the conflict between a group of vice-trading mobsters and a psychopath with an agenda preying on the dancers at mafia-controlled strip clubs. It’s a bit like a Hellhole New York update of M.

I suppose you could think of Matt Rossi (Tom Berenger, from Eye See You and Sliver) and his junior partner, Nicky Parzeno (Jack Scalia, of Endless Descent and Kraken: Tentacles of the Deep), as talent agents, although at first glance, they both look more like pimps. The stable of girls who work for them are not prostitutes but strippers, hired out on a nightly basis to the various go-go bars in and around Times Square. Naturally Rossi, Parzeno, and most of their clients are all mobbed up, but Matt tries to keep his mafia connections in the background, and to eschew the business practices of organized crime. It’s kind of a funny story how he got into this position. Like a lot of Italian kids who grew up in his neighborhood in the 50’s and 60’s, Matt was just sort of assumed to be mafia-bound, but he wanted nothing to do with that world. He was better than that, he thought— smarter than that— and he knew he had a marketable skill that could be exploited outside it. Rossi’s intended bypass route around gangsterism led through the boxing ring. He was good enough to go pro easily, and he made a name for himself early on as an honest fighter— no rigged matches for Matt Rossi, no sir. But one night a few years ago, Rossi got put up against a boxer with more heart than sense by the name of Kid Rio. Rio wouldn’t stay down no matter what Matt did to him, and the ref was content to let the fight go on so long as the obviously beaten man was still able to drag his battered carcass up off the canvass. When Rio finally did stay down, early in the tenth round, it was because Rossi had put him into a coma. He died a week later without ever regaining consciousness, and Matt hung up his gloves after that. Killing people was exactly the thing he was trying to avoid by going into boxing, you know? In the aftermath, Rossi just sort of drifted into mob employment in a state of total psychic defeat. Matt got so messed up inside that his girlfriend, Loretta (Melanie Griffith, from Cherry 2000 and Body Double), couldn’t deal with him anymore. First she took up heroin, and when even that didn’t numb the pain of their failing relationship, she had the good sense to walk out. She’s off the junk now, though, and dating another woman by the name of Leila (Rae Dawn Chong, of Quest for Fire and Tales from the Darkside: The Movie), which is the ultimate kick in the ass for Matt on a bunch of levels. You see, Loretta and Leila both work for him as dancers.

So basically, Rossi’s got plenty of problems even before somebody (an uncredited John Foster) ambushes Honey Washington (Ola Ray, from 10 to Midnight and The Night Stalker)— another of Matt’s girls— and puts her in the hospital with a plethora of superficial but vicious knife and scissor wounds. The worst of it is Honey’s fingers; her attacker cut a few of them off before he was finished with her. Several more of Rossi’s strippers, Leila included, are savaged over the coming week or so, too, plunging his entire life into disarray. Of his remaining high-earners, only Nicky’s girlfriend, Ruby (Janet Julian, of Humongous and Ghost Warrior), has the nerve to keep up her regular work schedule. A grief-stricken Loretta returns to her old dope habit after Leila succumbs to her injuries, transforming overnight from the agency’s star performer into a completely unreliable mess. Club owners like Frank (Joe Santos, of Flesh and Lace and Shaft’s Big Score) start complaining about broken contracts and lost earnings. Carmine (Rossano Brazzi, from The Final Conflict and Frankenstein’s Castle of Freaks), Matt’s mafia patron, starts pushing him to adopt a war footing, offering him armed goons to patrol his territory and visibly disapproving when Rossi prefers to keep things non-lethal at his end. And a homicide detective called Wheeler (Billy Dee Williams, from The Final Comedown and The Empire Strikes Back) begins making a pest of himself in Times Square, operating under the assumption that the attacks on strippers are part of an incipient mob war between Rossi’s masters and the Jewish gangs led by Carmine’s old enemy, Goldstein (Jan Murray).

Wheeler has it all wrong, of course. The man who’s been cutting up strippers in Times Square doesn’t give a shit about any mafia rivalry, and indeed isn’t consciously preying on Rossi at all. It’s just that Matt’s agency has something approaching a local monopoly on nude and topless dancers, so pretty much any such girl the slasher hits in the neighborhood is apt to be one of his. The best way to conceptualize Rossi’s de facto nemesis might be to imagine a cross between Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle and Seven’s John Doe. He believes that he is cleansing a city all too obviously in need of a good scrub-down, and he would be thrilled to learn that his activities have virtually shut down all the titty bars in Times Square. Wheeler’s myopic commitment to his mob-strife theory, meanwhile, effective ensures that the killer will be free to keep scrubbing for a long time. Unless, that is, Rossi can overcome his aversion to serious violence and take care of the problem like Carmine wants him to.

The thing you have to remember about the filthy, rotten, crime-ridden New York City of the 70’s and 80’s is that a lot of people loved it, and were sorry to see it go. Not infrequently, they were the same people who hated it, and wanted to see it burn. For many, it was almost a badge of honor to live in a city of nearly post-apocalyptic social breakdown; like the song says, if you could make it there, you could make it anywhere. That tension runs through practically all contemporary New York-centric art actually made by New Yorkers, and it grows noticeably stronger toward the end of the era, when efforts to clean up the city began to gain traction. Old Dirty New York still had a few years left in it in 1984, but Fear City is an excellent example of the phenomenon nevertheless. Ferrara’s loyalties are plainly divided, and that division is visible wherever you look in the film.

Let’s start with Matt Rossi; he is, after all, the protagonist. As a mobbed-up agent for an army of strippers, Matt is very much a part of the city’s rampant vice trade, but he’s extremely ambivalent about his position. At times, he seems to relate to the mafia almost as one of the ethnic clubs that sprang up in most major American cities during the Ellis Island era. Just the same, though, he has no illusions about organized crime, and he resisted becoming a part of it for as long as he thought he had any other options. In some ways, he continues to resist even now, like when he refuses to let Nicky rough up Frank over a past-due payment, or when he rebuffs Carmine’s offer to lend him some leg-breakers to patrol his turf. Matt has no patience for Loretta’s drug habit, either. So that makes him an “Honor and Humanity” sort of gangster, right? Even though that specific formulation is a yakuza thing instead of a mafia thing? Maybe. But notice how Ferrara consistently portrays Rossi’s commitment to nonviolence as a symptom of lost manhood, or at the very least as a situational weakness that his girls and his business can ill afford just now. Notice that the showdown between Matt and the killer is intercut with clips of the Kid Rio fight, so that we’re invited to read the return of Rossi’s killer instinct as a long-awaited personal triumph. And yet notice too that Matt emerges from that battle vaguely but visibly disgusted with himself for doing what the whole film has been assuring us he had to do.

The killer also embodies a complicated attitude toward the changes beginning to come over New York. Remarkably, Ferrara lets us see his face clearly from his very first appearance, and he’s not at all what you expect from either a mad slasher or a vigilante. His most conspicuous outward characteristic is his sheer ordinariness, but he’s ordinary in a socially and culturally significant way. Young, white, handsome, of no identifiable specific ethnicity, casually yet fashionably dressed, and apparently both affluent and college-educated (if we may judge from his enviably large loft apartment and the awareness of human anatomy with which he’s credited by the doctors who treat his victims), he’s like a nightmare vision of yuppie gentrification. Even his methods of attack are trendy, emphasizing as they do Japanese weapons and martial arts at a time when American pop culture was all agog over ninjas. By pursuing his bloody personal war against the vice business, he does in a more direct and brutal way what his demographic cohort was doing on the macro level, driving out the people who had flourished during Manhattan’s period of social unraveling. And obviously his attitude toward crime and vice is positively Giulianian. He’s the ideal villain, in other words, for New Yorkers who aren’t sure they really want the streets cleaned up, however tired they might be of getting mugged in the subway.

Detective Wheeler is the most instructive figure, however, fitting into the picture in all sorts of complicated ways. First, his giallo-flavored uselessness reflects both the real-world inability of the police to enforce the law in America’s largest city during this period, and the increasingly prevalent reactionary opinion that the best way to deal with a criminal was to shoot him yourself. However, the specific form his uselessness takes marks him as a creature of the same ecosystem as his enemies on the other side of the law. It’s no accident that Wheeler spends most of the film chasing after the imaginary participants in a mob war that isn’t actually happening. For one thing, that explanation for the rash of stripper-slashings fits very neatly into the worldview he’s developed over fifteen or twenty years on an increasingly outmatched police force. The detective sees Manhattan’s crime problem as a both a chronic, endemic condition— an incurable disease that can be treated only by managing the symptoms— and as the basically predictable end result of human venality. For him, it’s all about making money and settling personal scores, and there undeniably is an awful lot of that going on outside the law in his city. What’s more, that kind of crime has become for Wheeler something familiar and even comfortable. He’s become as desensitized to lawlessness as the citizens he and his department can’t seem to protect, and that’s made him complacent about how he approaches his job. He expects all police work to be a matter of finding the right mob boss to lean on or the right lowlife to sock upside the head. Also, if you look closely, there’s a clear element of racial and class resentment visible at the back of Wheeler’s “one size fits all” style of policing. On the one hand, he’s sick to death of seeing the fucking Italians get away with shit that would get a black perp locked up forever, and on the other, he’s filled with the classic working class hatred of freeloaders and parasites. On a certain level, he’s wedded to his mob-war theory because he wants the culprit to be some sleazy dago greaseball who’d rather skim his living off the top of a stripper’s tips than do an honest day’s work himself.

Ultimately, though, Wheeler won’t let himself see the slasher case for what it is because what it is threatens his complacency. Vigilantism isn’t just against the law, after all. It’s also a rebuke to legitimate law enforcement, a verdict from its perpetrators that the cops and courts aren’t doing their jobs— and it would have been hard to look around New York City in 1984 and conclude that they were. By admitting that he’s looking for a vigilante, Wheeler would be admitting in a sense that he and his whole department had failed. It would also place Wheeler in the uncomfortable position of recognizing that he and the slasher are, in an important sense, on the same side. And although Wheeler naturally has no way of knowing this, actually catching the slasher would put him in an even more uncomfortable spot, in that he’d see that the killer is exactly the sort of upwardly mobile narcissist that was soon to seize political control of the city, turning cops like Wheeler into the functional equivalent of their own private security force. Even Wheeler knows that he’s going to lose something in the transition when the new, clean New York finally arrives.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact