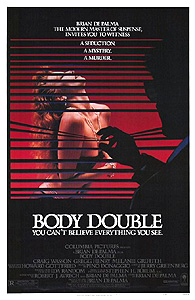

Body Double (1984) ***

Body Double (1984) ***

I really should have held Body Double in reserve until after I’d covered Dressed to Kill, but fuck it. I’ve already committed to reviewing this movie, and I accidentally overbooked the shit out of August even without trying to squeeze in one more film. We’ll just have to fill in the back-story some other time. What matters right now is that Dressed to Kill pissed off a whole lot of people, for a breathtakingly broad spectrum of reasons, and that writer/director Brian De Palma did not take the firestorm of criticism gracefully. Unless you’re at least aware of that background— unless you have some notion of the heat De Palma took for Dressed to Kill’s queasy combination of sex and violence, for its supposed revelry in sleaze and misogyny, even for its uncredited substitution of a 25-year-old Penthouse model for the 48-year-old Angie Dickinson in the latter’s nude scene— you’re apt to be thoroughly baffled by Body Double, De Palma’s third and thus far final foray into pure Hitchcockolatry. Body Double was very much a response to the controversies that raged around its predecessor, and it serves to dramatize an important difference between successful Hollywood directors and the rest of us. When you’re one of the former, you can get people to put up millions of dollars so that you can capture your temper tantrums on film. In Body Double, De Palma essentially says, “So you thought Dressed to Kill was pointlessly nasty, misogynistic filth, eh? Well I’ve got your gratuitous sex and violence right here, you fuckers!” And at the same time, the film takes weirdly oblique potshots at the scolds who can’t distinguish cinematic fantasy from reality, along with much more direct ones at the phoniness and hypocrisy of the movie industry. It is the closest thing to an unmoderated eruption of its creator’s id that American commercial cinema was still capable of producing in 1984.

Jake Scully (Craig Wasson, from Schizoid and Devil on the Mountain) is a crummy actor who earns almost no money making even crummier movies. His career is such a sorry joke that he can’t afford a place of his own, and his fiancee, Carol (Barbara Crampton, of Chopping Mall and From Beyond), is the one with her name on the lease to their house. Currently, Jake is playing the part of an effete, undead Billy Idol wannabe in a cheap piece of shit called Vampire’s Kiss, but that turns out to be a rather problematic gig for him. Scully suffers from acute claustrophobia, and somehow it never occurred to him that his neurosis might cause trouble on a project that requires him to spend a lot of time lying in coffins. Disgusted with the resulting delays, the director (Dennis Franz, from Psycho II and The Fury) tells him to take a few days off, and then recasts the role behind his back. And as if that weren’t enough, Jake comes home from his early dismissal to find Carol in bed with another man. He doesn’t even get the hollow satisfaction of kicking her out, since it’s technically her damn house!

While bumming around town in search of both a new gig and a room he can sublet, Scully keeps bumping into another actor who calls himself Sam Bouchard (Gregg Henry, of Bates Motel and Raising Cain). When the two men finally get to talking for real one afternoon, it comes out that Scully and Bouchard might be of some actual use to each other. Sam has a curious living arrangement whereby he gets to stay rent-free as a house-sitter for a ridiculously wealthy businessman, whose work rarely permits him to stick around LA to enjoy his lavish, retro-futuristic apartment. (Seriously, this place ought to be tromping along the Thames waterfront, lighting ironclads on fire with solar heat rays.) However, he just got a five-week job up in Washington, which would leave his friend’s three-bedroom Martian tripod unattended for longer than their agreement would normally permit. And Jake, as we’ve already established, urgently needs a place to live at least slightly more permanent than his favorite bartender’s sofa. Scully moving into the flat for the five weeks Bouchard is away is obviously a win-win situation. Jake quite likes the apartment when Sam brings him over to see it, and the most burdensome responsibility that looking after it entails is to keep all the goddamned houseplants alive and happy. Oh— and there’s a sort of secret perk to living there that Bouchard accidentally discovered one night while peering through the telescope that commands a spectacular view of the valley below. The nearest house in that direction belongs to a gorgeous young woman (Deborah Shelton, of Blood Tide and Nemesis), and every night, like clockwork, she does a languorous striptease in front of her bedroom window. Spying on this strange nightly performance at Sam’s instigation plainly makes Jake uncomfortable, but not uncomfortable enough to stop doing it.

Scully’s continued perving on the woman down the hill quickly involves him in things he would rationally want no part of. There’s a man in her life, for one thing, and from what Jake can see through the landlord’s telescope, that man is an utter bastard. Getting routinely slapped around by her boyfriend or husband or whatever might be the least of the immodest neighbor’s problems, though. One night, Jake observes that he isn’t the only one observing. The other spy looks like real trouble, too, all bulging muscles and crazy eyes. The following morning, Jake finds himself turning onto the street at the same time as his neighbor— and at the same time as the bigger, scarier peeping Tom, too. Concerned, he decides to follow the woman, and this is where his behavior starts to turn really dubious. The neighbor— her name is Gloria Revelle, by the way, although Jake won’t be finding that out for a while yet— goes to a swanky shopping mall, where she arranges over a pay phone to meet somebody at a beachfront hotel; Scully listens in, and takes note of the rendezvous point. Then she heads inside to buy some notionally sexy lingerie at Bellini; Scully peeps on her in the changing room (Gloria isn’t too careful about closing the curtains) through the store’s front window, brazenly enough to get security called on him. Jake almost talks to Gloria in the elevator a bit later, but then he has a claustrophobic panic attack, and can’t bring himself to say anything. By that time, it’s become apparent that Gloria’s other stalker is at the mall, too, but whatever he’s planning, he evidently lacks the nerve to try it in a place this public. Back in the garage, Gloria disposes of her original panties in a trashcan near the valet station; Jake pockets them. Finally, Scully (like the second stalker) follows Revelle to her appointment on the shore, where the person she was supposed to meet has stood her up. The beach is far less populated than the mall had been, and Stalker #2 looks just about ready to make his move. Here, at last, is Jake’s opportunity to initiate contact and explain what he’s seen while looking like only the second-creepiest motherfucker Gloria has ever met. He accosts her beside the changing tents (bad choice, as we’re about to see), and tells her that someone is following her; she says she knows, and asks him if her husband is paying him to keep tabs on her. While Scully is trying to squirm his way off of that hook, the other stalker charges forth from between the tents, seizes Gloria’s purse, and takes off running up the beach. Jake gives chase (that should be worth a few kiss-ass points, right?), but his big rescue is partially foiled when the robber ducks into a tunnel beneath an overpass. Scully’s claustrophobia acts up again, leaving him unable to do anything about it while the thief rifles through the stolen purse, and smilingly withdraws holding what looks like a credit card. I guess sometimes the old college try is good enough, though, for when Gloria catches up to Jake and helps him out of the tunnel, she thinks nothing of making out with him in a sequence that, were this an Andy Milligan movie, would surely be marked by a “SWIRL CAMERA” notation in the shooting script.

I recommend you don’t get too attached to Gloria Revelle, however. Body Double may devote most of its energy to copying Rear Window and Vertigo, but structurally speaking, this is a Psycho rip-off all the way. Making direct contact with Gloria does nothing to constrain Jake’s urge to peep on her, but the performance is rather different when he trains the telescope on her windows that evening. The other stalker is inside the house, sneaking about and collecting as much of Gloria’s jewelry as he can find, and we who have seen Slumber Party Massacre will be thinking he has worse than burglary on his mind when Scully catches sight of the giant electric drill he’s carrying around with him. Jake tries once more to play the hero, even going so far as to collar a pair of passing joggers to help him break through the front door and fend off Gloria’s decidedly unhelpful guard dog, but by the time he makes it up to the bedroom, it’s too late. Gloria is dead, the killer is gone, and the only thing left to do is to tell Detective Jim McLean of the Los Angeles Police Department (Guy Boyd, from Ghost Story and Carnosaur 2) what happened. And naturally, the detective is quick to pick up on the 17,000 ways Scully’s story makes him look like a pervert with something to hide.

This is where things get weird. I said before that Body Double owes its structure to Psycho, by which I meant that it uses the murder of a major character at about the halfway point as an excuse to transform itself into a very different sort of movie. I can virtually guarantee that nobody who comes into this film cold will ever see what it turns into coming. Soon after Gloria’s murder, Jake finds himself watching some porn channel on cable TV, and he happens to catch a commercial for a new release called Holly Does Hollywood. The ad spot features a clip of porn queen Holly Body (Melanie Griffith, of Cherry 2000 and Cecil B. Demented) doing a striptease in front of a mirror, and damned if it isn’t the very same routine that Jake got used to watching every night through Gloria’s window! Holly Body’s physique is strikingly familiar, too, and it suddenly dawns on Scully that he never once saw his neighbor’s face while he was peeping on her— it was always obscured by shadows, dark glasses, and trailing hair. It’s perhaps not the most logical of logical leaps from there to suspecting that a porn star was inexplicably impersonating the girl next door, but once Scully’s brain goes there, he simply has to know. Finding out will require meeting Holly Body. Meeting Holly Body will require auditioning to be in her next movie. And the next thing we know, Body Double is looking less like Hitchcock’s Greatest Hits, and more like a Michael Mann remake of Salon Kitty.

Despite the arguably overwrought complexity of my rating system, I’ve never really arrived at a satisfactory way of dealing with well made, deliberately bad movies. I honestly don’t know whether Body Double is a three-star film or a negative-three-star film, but I’m settling on the former because I don’t think De Palma wants us to be able to tell. Body Double’s implausibilities, absurdities, inanities, dangling plot threads, and so on— all of which it has in great abundance— are without question meticulously calculated, not just in the sense that they’re obviously exactly what De Palma wanted to do, but also in that the natural audience reaction to them is obviously exactly what he wanted to get out of us. If and when Body Double sucks, it’s because it was designed to suck. Along with being a Hitchcockian suspense film, it seeks to satirize the artifice, excess, and bullshit of 1980’s Hollywood, and its modus operandi is to consist of little else but artifice, excess, and bullshit.

Beginning with the artifice, I can think of very few movies that go so far out of their way to draw attention to the fact that they are movies. The underlining begins with the main titles and opening credits, which are designed and presented as if they were those of Vampire’s Kiss, and which conclude with a close-up on Jake Scully, in terrible vampire makeup, lying in a coffin. That, of course, segues into the claustrophobic attack that gets Jake fired, and then into the real story. Plenty of movies use broadly similar opening fake-outs, but rarely do you see one try to sucker the audience with a setup that belongs in a completely different genre, and which therefore has no real chance of actually succeeding. The trick is that De Palma doesn’t really want to fake us out at all— he wants us to think about fakeness as a concept, since that’s what the whole story is built around. The coffin scene is then reprised in overtly allegorical form— which is to say, allegorical from the character’s own perspective— at the climax, when the killer tosses Jake into an open grave and sets about burying him alive. So now we’re privy to the simulations of reality being served up by the protagonist’s own brain, and it isn’t totally out of the question that the whole remainder of the film from there to halfway through the closing credits is nothing more than that. Nothing in Body Double is more artificial, though, than the “relationship” between Jake and Gloria. Even before the revelation that the woman whose sexy dances Scully watched through the telescope wasn’t really Gloria in the first place, the bond between the two characters is never more than a figment of Jake’s wishful imagination. Up until the moment it kills her off, Body Double treats Gloria as if she were Jake’s love interest, but it does so without plausible basis— and De Palma definitely wants us to notice that. Why else would he make their kiss outside the tunnel into the silliest, chintziest, phoniest, most unconvincing moment in the whole film, even going so far as to shoot it in front of a distractingly awful rear-projection backdrop?

The excess in Body Double, meanwhile, comes in two flavors: violence and sex. I have to assume that the echoes of Slumber Party Massacre in the big murder set-piece were no accident, since not only does the killer use the same unwieldy yet evocative weapon, but De Palma also employs many of the same Freudian frame setups during the attack. I’m curious, though, whether De Palma was aware of that movie’s pre-release history, because the way he executes the lift, it’s almost as if he were making the Slumber Party Massacre that Rita Mae Brown originally wanted. And when the killer’s identity is finally revealed, the murder takes on several layers of further retrospective Brownishness, subtly inviting a feminist reading that could not seem more starkly at odds with the scene’s superficial subject matter. De Palma makes the guignol grander than his apparent model, however, so that the sequence also functions as a giant middle finger extended before the faces of everyone who thought he’d already gone too far in Dressed to Kill. The sex excess, inevitably, comes into play when Scully goes undercover in the porn industry. I’ve read that De Palma wanted the second half of Body Double to include milieu-appropriate unsimulated sex scenes, and while I’m somewhat skeptical of that claim (particularly in light of Ron Jeremy’s accusation that the Dressed to Kill rape scene strayed over the hardcore line), everything about Scully’s porno adventure that made it onto the screen might as well have been calculated to stop anyone from putting it past him. Any time a suspense movie puts its plot on hold for a smuttied-up version of Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Relax” video, the vast majority of bets are obviously off.

And then, finally, there’s the bullshit. I’m fairly confident it was this aspect of Body Double that led Michael Weldon to dismiss it as “De Palma’s worst showoff Hitchcock copy,” because any attempt to engage this movie without a thick containment suit of irony is sure to leave one with the impression that it’s really pretty dreadful. The villain’s scheme is nonsensical enough to be suitable for a fifth-rate 70’s giallo, Scully’s behavior subsequent to about the second reel is comprehensible only if we assume that a pissed-off Greek god is meddling with his fate, and if it weren’t for the absence of a comic-relief sidekick even dumber and lazier than he is, you’d think Detective McLean had wandered in here from some 1940’s Poverty Row second feature. There have to be a hundred simpler and less gonorrheic ways for Jake to gain access to Holly Body than to become LA’s least competent porn performer, and there have to be a thousand more effective ways to learn what he wants from her than erecting a teetering Jenga tower of ever less plausible lies. I say again that De Palma must have meant for Body Double to come out like this— it’s all too exact in its wrongness to be an accident. That doesn’t change the fact that it takes a certain amount of psychological preparation to get much out of this movie. Having set out to make the best piece of complete shit he was capable of, De Palma succeeded admirably. The aim itself is so utterly mad, though, that many if not most audiences are apt to find it largely self-defeating.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact