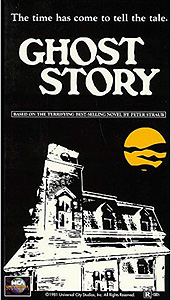

Ghost Story (1981) **

Ghost Story (1981) **

Okay— confession time. I’m honestly not sure whether I’m really capable of being fair to this movie. You see, Peter Straub, who wrote the novel on which Ghost Story is supposedly based, is far and away my favorite author of fiction. For the sake of those not familiar with his work, Straub is something like Stephen King’s Bizarro World counterpart. Like King, he is a Northeasterner specializing in horror who got his start in the mid-1970’s, and who was catapulted into best-sellerdom early in his career. Stephen King fans will also note certain authorial mannerisms that Straub has in common with their favorite writer, while both men are on record as admirers of the other’s work, and the two of them have even collaborated twice. But while King’s writing is avowedly, even aggressively populist, featuring an easy, conversational style and generally straightforward, linear plotting, Straub is more literary. In fact, he wrote a couple of completely straight dramatic novels before deciding that horror was where his real talent lay. Straub’s diction is also more complicated, almost British-sounding (no surprise there— he lived in London for a very long time), but the starkest point of contrast with King is the manner in which he constructs his stories. Time is extremely fluid in Straub’s writing, and hardly any of his books are laid out as a simple, chronological sequence of events. In the case of Ghost Story, the plot literally runs backwards for the first half of the novel, before switching gears to work its way back around to the events of its first chapter. The result is that Straub’s stories seem to knit themselves together inside out and upside down, making reality a very slippery thing until usually the last third of the book, and it’s therefore hardly surprising that very few of his novels have ever been turned into movies— most filmmakers would barely know where to start. Ghost Story is probably my favorite single Peter Straub book (he’s written better, but the true greatness of his best work— the three novels and numerous short stories that might be called the “Blue Rose” cycle— is apparent only when all the writings that comprise it are taken together), and that fact makes it very hard for me to judge John Irvin’s movie version on its own merits. For Irvin’s Ghost Story is, bar none, the most thoroughly wrong-headed film adaptation of a novel that I can ever recall having seen.

Rather than dump us right into the action at a point calculated to baffle us into attention, the movie starts off with introductions. The four old men of the Chowder Society— Sears James (John Houseman, from Rollerball and The Fog), Ricky Hawthorne (Fred Astaire— yes, that one!), Dr. John Jaffrey (Melvyn Douglas, of The Vampire Bat and The Old Dark House), and Edward Wanderly (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.— again, yes, that one)— are nearing the end of one of their monthly get-togethers at Sears’s place. Now before you ask me, no. I have no fucking idea why this bunch call themselves the Chowder Society. In the novel, the name came from Ricky’s wife, Stella (played here by Patricia Neal, of Stranger from Venus and The Day the Earth Stood Still), who coined it as a mild expression of her thinly veiled contempt for her husband’s friends. But since we’ll later learn that the men were already using that collective handle as early as 1929, that can’t possibly be the case here. In any event, what the four old friends do together on these occasions is take turns trying to scare the crap out of each other with ghost stories, and Sears, whose turn it is this month, seems to be pretty good at it. In fact, one is tempted to suspect that their “monthly spook story” has something to do with the intense, recurring nightmares from which James, Hawthorne, Jaffrey, and Wanderly all suffer. At the very least, that’s certainly what Stella and Jaffrey’s live-in housekeeper, Milly (Jacqueline Brookes, of The Entity and The Good Son), think.

Meanwhile, a few hours to the south in New York City, Edward Wanderly’s son, David (Craig Wasson, from Schizoid and A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), is having a very strange argument with the naked girl lying face-down on the bed in his penthouse apartment. While she ignores him, David asks insistently and repeatedly who she is. Then he starts asking the girl what she is. Eventually, she says something that stops David in his tracks: “I am you.” Maybe so, but as David is about to learn, she’s also some kind of evil revenant, and when she picks her face up off of that pillow, the left side of it is just about completely rotted away. Wanderly recoils in terror, and in doing so goes ass-first out the window behind him.

Soon thereafter, the elder Wanderly places a call to his other son, Donald (also Craig Wasson, but with shaggier hair and no moustache), summoning him to the small New England town of Milburn for David’s funeral. Don, an author by trade, is the ne’er-do-well of the family, and Edward plainly finds his presence around the house just barely tolerable. The elder Wanderly is especially dismissive of his son’s seemingly irrational contention that David’s death was no accident. Evidently, the dead man’s fiancee was Don’s girlfriend first, and on the basis of his own experiences with her, Don worries that she may actually have murdered his brother.

Don’s got the right idea, of course, but there’s a hell of a lot more going on here than simple murder. Early the morning after David’s funeral, a befuddled Edward goes wandering off through the snowy streets like a man in the grip of senile dementia. Actually, he’s in the grip of a hallucination— he thinks he sees David beckoning to him from down the street a ways. Eventually, Wanderly winds up on a bridge over a frozen river, at which point a hideous female specter appears to him, and scares him over the rail to his death. The physical resemblance between this ghost and the one that was passing as David’s fiancee in New York is surely not coincidental.

That’s only the first of many strange things to happen in Milburn. An escaped lunatic named Gregory Bate (Miguel Fernandez, who had played a very small part in Rabid) arrives in town with his pre-teen brother, Fenny (Lance Holcomb, of Venom and Christmas Evil), and begins harassing both Don Wanderly and the surviving members of the Chowder Society, having set himself up in a big, abandoned house to which the old men have some closely guarded secret connection. Then Don finds an old photograph in his father’s basement, which depicts the Chowder Society in their youth, posing with a girl he’s certain he’s seen before. This leads him to crash a Chowder Society meeting to tell what he has come to believe is a ghost story of his own. Some years ago, when he was teaching a literature course at a small college in Florida, Don conducted a brief but intense affair with his boss’s secretary, Alma Mobley (Alice Krige, who would go on to appear in Reign of Fire and Star Trek: First Contact). Alma was an odd, secretive girl, and she rapidly became obsessed with Milburn, the town where Don grew up. Don, meanwhile, was becoming obsessed with her, to the extent that it totally destroyed his nascent teaching career. But his feelings for Alma changed completely when the two of them took a week-long vacation together at an isolated beach house. Alma sleepwalked nearly every night, and whenever she did, she would say strange and frightening things. After a few days, Don noticed— and who knows how he managed to miss this before— that Alma’s body was always cold to the touch, apparently much more so than her habit of roaming around the beach house nude could account for. By the time the vacation was over, Don had been so thoroughly creeped out that he no longer wanted to marry Alma, and the girl disappeared without a trace the very day after he told her so. But soon thereafter, she turned up again, this time in New York, where David fell for her just as hard as Don had. We know what happened to David, of course, but what we haven’t heard is that the police who investigated his death could find no more sign of Alma than Don could the day after he broke off his own relationship with her. What makes Don think this might be a ghost story is the photo he found at his father’s place. The girl in the picture is Alma Mobley.

Don’s right about Alma having been a ghost. When the Chowder Society knew her, it was 1929, and she was calling herself Eva Galli. A stupendously wealthy orphan of Anglo-Italian extraction, she caused a huge stir in high society when she moved into Milburn (renting the mansion that the Bate brothers would claim as their own some 50 years later), and all four members of the Chowder Society fell in love with her. It was Edward Wanderly whose attraction to her was the strongest, however, and it was also toward Edward that Eva was fondest. But one night, a dangerous mixture of sex, jealousy, and way too much liquor led to the girl’s accidental death, and in a panic, the four lads stashed her body in the back seat of a car, and drove it into Dedham Pond. Inevitably, it is this ancient grievance that now motivates the undead woman, and her efforts (only half successful) to seduce and destroy the Wanderly brothers were just the beginning of an elaborate program of belated supernatural revenge.

It would be difficult to find a film adaptation of a novel that disregards its source material much more completely than Ghost Story. John Irvin and screenwriter Lawrence Cohen have changed just about everything from minor details of setting and character all the way up to the main thrust of the story itself. Straub’s novel, despite its title, isn’t really a ghost story at all. There are ghosts in it, but they are of minor importance. In Straub’s version, Eva Galli and the Bate brothers are something totally inhuman, and it seems that Galli, at least, had never been human in the first place. Instead, Straub makes her one of a race of effectively immortal, predatory shape-shifters which he posits as the basis for most folkloric tales of supernatural evil— the werewolf, the vampire, the ghoul, the wide array of deadly shape-changers that figure in Asian, African, and Native American mythology. He even finds a way to work in the modern-day spook stories about livestock being exsanguinated by something that leaves no footprints and kills with surgical cleanliness and precision. Next to this complex and multifaceted premise, Ghost Story the movie looks tired and derivative indeed. Beyond that, this movie’s creators seem almost to have made a game of changing things around, just for the sake of doing it. Milburn has moved from western New York to somewhere in New England; Don’s teaching gig has moved from Berkeley to Florida; the venue of David’s demise has shifted from Amsterdam to New York City. Stella Hawthorne and Milly Sheehan have virtually traded personalities. The fifth member of the Chowder Society, Lewis Benedikt, has been eliminated altogether, and his characteristics divvied up among the other four men: Ricky Hawthorne gets his looks, Sears James his money, and John Jaffrey his helpless ineffectuality. Some of the changes are understandable— having Edward call Don out to Milburn in response to David’s death makes for a far more streamlined narrative than Straub’s means of bringing him to town, which is an important consideration when trying to squeeze a 600-page story into an hour and a half of film— but a lot of them accomplish nothing whatsoever.

A related point concerns the movie’s dialogue. Ghost Story’s script includes quite a number of verbatim quotes from the book. This is actually not a good idea, because Cohen’s writing style clashes with Straub’s quite clamorously, and the lifted lines sound clunky and artificial the way Cohen uses them. And in keeping with the rest of the screenplay, hardly any of this quoted dialogue is assigned to the same characters who originally spoke it, with the result that the core motivations of a number of characters are stood on their heads.

Things get a little better once we get past the story. Melvyn Douglas and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. put in some pretty lousy performances, but the rest of the cast is quite good. I personally would have cast Christopher Lee in the part, but John Houseman makes a perfectly believable Sears James, especially given the harder-edged personality that the movie ascribes to him. Basically, Houseman is just retooling his performance as Professor Kingsley in The Paper Chase, but seeing as Sears is supposed to be Milburn’s foremost lawyer, such a treatment of the character seems rather appropriate. Fred Astaire does an even better job with Ricky Hawthorne, who is the only character in the movie that retains all the complexity of the print version, and is thus the only one that offers an actor of Astaire’s experience anything interesting to work with. Alice Krige’s role is the most problematic. She does a competent job with Eva Galli and Alma Mobley (except for a couple of times when she trips over a line of dialogue or a bit of stage direction so poorly written that hardly anyone could be expected to pull it off), but she’s just plain wrong for the part. She’s too ordinary looking, and has none of the exotic quality that several of the characters attribute to Galli/Mobley. I simply can’t see six different men losing their wits and throwing away their lives and careers for Alice Krige.

In the final assessment, what you think of Ghost Story the movie will probably depend to a great extent on whether you’ve read and enjoyed Ghost Story the book. Without Straub’s much richer, much more original, and much more fully realized version of the story to compare it to, the movie will probably seem serviceable enough, especially toward the end, after the clumsiest scenes and the most annoying characters have been gotten out of the way. Fans of the novel, however, will be asking for trouble when popping this tape into their VCRs.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact