Dressed to Kill (1980) ***

Dressed to Kill (1980) ***

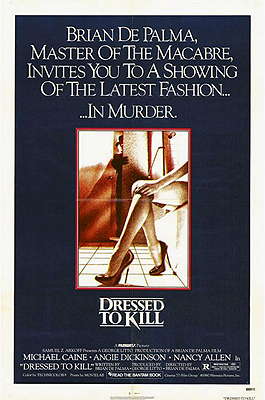

You don’t have to watch one of Brian De Palma’s movies from the 1970’s for very long to see something that reveals his admiration for Alfred Hitchcock. Few if any of De Palma’s early horror and suspense films are without a reference here or a tribute there— even The Phantom of the Paradise pokes a moment of affectionate fun at the Psycho shower scene. There’s a difference, though, between acknowledging one’s influences and emulating them, and as the 1980’s dawned, De Palma’s Hitchcock cribs shifted from the former mode to the latter. Dressed to Kill was the project where that transformation took full effect. It is, for all practical purposes, De Palma’s rebuild of Psycho, right down to the bait-and-switch protagonist, the cross-dressing killer, and the resolution hinging on an unsuspected case of dissociative identity disorder. Hitchcock himself was incensed when he saw Dressed to Kill at the instigation of John Landis; in response to Landis’s attempts to convince him that he should be honored by De Palma’s homage, Hitchcock snorted, “More like fromage!” Of course, artists with big egos often take offense at such things. I think they interpret it as a threat to their standing when some young upstart successfully replicates their techniques. Then again, maybe Hitch also saw something in Dressed to Kill that isn’t immediately obvious. Skulking around inside this seemingly fawning tribute to Psycho is a subtle critique of it, a suggestion that Hitchcock didn’t take the premise as far as he should have, and that the time had come for an interpretation of the same themes that was a little more aggressive, a little less squeamish, and a lot less eager to make tidy returns to the status quo ante in time for the closing credits.

Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson, from The Norliss Tapes and The Resurrection of Zachary Wheeler) doesn’t like her husband (Fred Weber) very much. He’s inconsiderate, insensitive, and no good at all in bed, and some sense of the enthusiasm with which she greets his habit of groping her awake for a first-thing-in-the-morning fuck may be gained from the way her subconscious edits the stimulation of his hands into her dreams— the first thing we see is her dreaming of a languorous and sensual shower being interrupted by a rapist attacking her out of physically impossible nowhere. Kate’s teen-genius son, Peter (Keith Gordon, of Jaws 2 and Christine), isn’t fond of Mike, either, but kids often have trouble accepting their stepfathers, even when their real dads weren’t killed in Vietnam. Peter pours all the psychic energy he might otherwise spend on family resentment into his inventions, but Kate doesn’t have that option. She has to manage her life’s dissatisfactions the officially approved way, with regular visits to psychiatrist Robert Elliott (Michael Caine, from Children of Men and Inception). At the same time, Kate recognizes that what she really needs is something that Elliott would never recommend for her— a nice, tawdry, adulterous affair to make her feel properly appreciated by someone. Indeed, she’d really like to have an affair with Elliott— and has told him as much!— but no chance there. So far as we can see, he’s quite possibly the only truly ethical psychiatrist in the history of motion pictures, and he’s an ethical husband on top of it. With that avenue foreclosed to her, Kate picks up a stranger by the name of Warren Lockman (Ken Baker, who is not to be confused with 80’s dwarf actor Kenny Baker, however delightful that would make these next few scenes) at De Palma’s own favorite romantic stalking ground, the Museum of Modern Art. Kate’s tryst with Warren is everything she wanted it to be… until she goes looking in his desk for stationery on which to write him a “Thank you and goodbye” note, and discovers a memo from the municipal health department informing him that he’s tested positive for venereal disease. Don’t blow the Sad Trombone just yet, though, because Kate’s evening is about to take an even sharper turn for the worse. On the way out of Lockman’s apartment, she is followed down the hall by a man in a blonde wig, sunglasses, and unconvincing drag, who carves her up with a straight razor as soon as they’re alone together in the elevator.

Kate’s murder is witnessed by emergency backup protagonist Liz Blake (Nancy Allen, of Strange Invaders and Children of the Corn 666: Isaac’s Return). Unfortunately, the local police precinct assigns the case to Detective Marino (Dennis Franz, from Body Double and Deadly Messages), three-time winner of the Fraternal Order of Police’s Laziest Cop in the Universe cup. Marino knows nothing of the incident save what he gets from Liz, and yet he immediately decides to treat her as a suspect instead of a witness. Why? Because Liz is a call girl, and apparently all crimes (and their perpetrators) are interchangeable to the detective. For that matter, Marino also treats Dr. Elliott like a suspect when he comes in to be interviewed on the subject of his patient’s death. With Elliott, though, there’s at least a halfway-sensible reason— what if the uncooperative doctor is protecting another of his patients, who met Kate in the waiting room of Elliott’s home clinic and marked her for later murder? And in point of fact, Marino may be closer to the truth with that than Elliott cares to admit. When the psychiatrist returns home, he finds a message on his answering machine from someone calling himself “Bobbie” (you can practically hear the feminine spelling), who is apparently fed up with waiting for Elliott to okay him for gender-reassignment surgery. Not only is he seeking a second opinion from another shrink named Levy (who’ll be played by David Margulies, of Ghostbusters, when we meet him later on), but he’s also decided to punish Elliott for his intransigence by killing somebody with a razor he stole from the doctor on his last visit. Bobbie didn’t specify whom he intended to kill, but I think we can take a pretty good guess at this point.

Marino doesn’t realize this, but there was a spectator to his inept and arguably corrupt interrogations. Peter Miller, called in to identify his mother’s body, used one of his contraptions to listen in on Marino’s talks with the witness-suspects, and he justly has little faith in the detective’s abilities. The way Peter sees it, he owes it to his mom to make sure her killer is brought to justice, and the one thing he’ll say for Marino is that Elliott’s waiting room does sound like the most plausible starting point for an investigation. To that end, he seeks out Liz Blake for a little alliance. They’ve each been approached by Elliott with offers of psychiatric aid to cope with their shared trauma, and Marino’s “close enough for government work” attitude toward crime-solving gives her at least as good a reason as Peter to take up amateur sleuthing just now. If they put their heads together, they might be able to exploit Elliott’s interest in them to sneak a look at his appointment book, and see who was likely to be hanging around the clinic while Kate was on the premises. The trouble is, Bobbie saw Liz seeing him kill Kate, and somehow or other, he’s figured out who she is. Obviously Bobbie’s best bet now for staying ahead of the cops is to take out Liz, too— and that’ll go just as much for Peter should he be caught interfering.

When I sat down to watch Dressed to Kill, the main thing I knew about it was that it provoked a huge media outcry which in turn provoked De Palma to make Body Double. Dressed to Kill was attacked for being too violent, too sexy, and too much of both at the same time. Feminists took De Palma to task for making a movie in which one heroine was a prostitute and the other an adulteress who gets killed while slutting around with a man she’s never met. Ron Jeremy cried foul on Kate’s rape dream, accusing Dressed to Kill of crossing the line into hardcore territory in the brief close-up of the attacker’s hand seizing her by the crotch. Even Angie Dickinson’s body double, Victoria Johnson, raised a stink over Dickinson’s claim (encouraged by the producers) to have done her own nude scene. Knowing all that and nothing much else, the thing I was most shocked by in Dressed to Kill was how tame the film felt. To get so bent out of shape over Dressed to Kill would seem to require ignorance of every major development in horror cinema since Blood Feast in 1963. I suspect, though, that such ignorance was exactly the problem that this movie encountered. In 1980, the horror genre was nearing the end of a long period of ghettoization. Despite some hits of seismic proportions during the preceding dozen years— Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, Jaws, Halloween, and so on— horror hadn’t attracted a commensurate amount of critical attention outside of the fan press, the very existence of which tended to reinforce the genre’s dismissal by mainstream reviewers as irrelevant kids’ stuff. Meanwhile, the nasty, edgy horror films that started cropping up in great numbers during the late 60’s were mostly hidden away at drive-ins and grindhouses, where nobody but the truly committed fans would ever find them. Dressed to Kill, on the other hand, got a wide release to normal theaters, where normal people went to watch normal movies. When those audiences and critics got the vapors over it, as if they hadn’t seen or didn’t know about Last House on the Left, I Spit on Your Grave, or The Toolbox Murders, that was probably because they hadn’t and didn’t. And if you went into this movie expecting even something like Carrie, I can see how what you got instead would come as an unwelcome shock. That doesn’t mean the complaints weren’t largely misguided, though.

Bizarrely, Victoria Johnson had the best grounds for griping, however petty her objection might seem. Dickinson’s boasts did cut Johnson out of whatever credit she deserved, although you’d have to think that was nothing out of the ordinary in her line of work. Ron Jeremy had the kernel of a point, too, in that there was no way a lower-budgeted film by a less well-connected director could have gotten away with that crotch-grab, but the fact remains that the shot doesn’t show what he claimed it does. It’s the feminist indictment of Dressed to Kill, however, that lands farthest off-target. To accuse this movie of misogyny requires reading moral intent into a film whose most striking characteristic is its complete rejection of moralizing. It’s absurd to imagine that Kate is being punished for her sins, because the whole rest of the movie is about the universe unjustly shitting on people. Peter didn’t deserve to lose his father to one of the 20th century’s more manifestly pointless conflicts. Bobbie didn’t deserve to be born with the wrong set of genitals and secondary sex characteristics. Liz doesn’t deserve to have her safety entrusted to an indolent peckerwood like Marino. And nobody deserves to live in an anomic hellhole like Dressed to Kill’s Manhattan, where there’s a rape gang in every subway stop, and the cops’ response to anything short of a dead body boils down to, “Eh. Sucks to be you.” What part of that gestalt suggests that Kate’s fate could have anything to do with what she deserved?

The amorality of Dressed to Kill’s universe is the strongest example of De Palma diverging subliminally from the Hitchcock model, which was generally very particular about seeing normality restored in the end— the conspiracy thwarted, the criminal behind bars, the falsely accused exonerated, whatever. De Palma may use barely a trick here that wasn’t developed or perfected by Hitchcock, and he may lift the contours of the plot wholesale from Psycho, but Dressed to Kill commits to its cynicism in a way that I’ve never seen a Hitchcock movie do. You see it most clearly in the epilogue. A surprisingly long sequence depicts the killer escaping from a Bedlam-like interpretation of the Bellevue mental hospital to track down Liz and attack her in her apartment. At least part of this epilogue is revealed to be a Carrie-like dream, but even if we take the whole thing to be nothing but Liz’s nightmare, the mere fact that she’s having such nightmares is an acknowledgement that not everything has worked out for the good. The dead are still dead, the insane are still insane, the world is as hostile and threatening a place as it ever was, and now Liz has post-traumatic stress disorder on top of it all. Horror movies in 1980 were willing— indeed, in some ways expected— to confront such realities, and De Palma seems to be arguing that the sunnier endings typical of old-timey fright films are not just obsolete, but downright dishonest. More than anything, it’s that inversion of how the stolen material is used that makes De Palma’s plagiarism here tolerable.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact