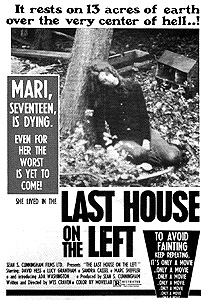

The Last House on the Left / Krug and Company / Grim Company (1972) *½

The Last House on the Left / Krug and Company / Grim Company (1972) *½

If there is any one movie that can be taken to symbolize the trend toward utterly unapologetic viciousness in the horror films of the 1970’s, Wes Craven’s The Last House on the Left is probably it. I wish I could give the nod to a good movie instead, or at least to one that actually accomplishes what it sets out to do, but reputation and influence easily outweigh quality in such matters, and The Last House on the Left has more of both working for it than any other credible contender. Certainly its 30-odd years on the BBFC’s banned list betoken a film with a singular capacity for making enemies of moral crusaders and arbiters of taste, despite its paradoxical arthouse pedigree. (Though this fact was little publicized in 1972, The Last House on the Left is really nothing more than an uncredited exploitation reworking of Ingmar Bergman’s highly regarded The Virgin Spring.) Everyone knows that this is an ugly, ugly movie— even the people who’ve never seen it. But the Last House on the Left of legend is a rather different beast from the Last House on the Left that you’ll find on the racks at your local video store. While the former is the ultimate in kick-you-in-the-face 70’s gore-horror, the latter is the movie that proves that in the right hands, torture, rape, murder, and relentless psychological brutalization can in fact be kind of boring.

An opening title card informs us that “The following is based on a true story. The names have been changed to protect those still living.” One assumes that was reckoned to have slightly more horror movie street cred than “The following is based on a much-respected Swedish art film. The names have been changed because none of you dumb-asses would ever be able to pronounce ‘Ingeri’.” Tomorrow is Mari Collingwood’s seventeenth birthday, and Mari (Sandra Cassell, from Teenage Hitchhikers and The Filthiest Show in Town) and her friend, Phyllis Stone (Lucy Grantham), are celebrating by going downtown to Manhattan to see a band called Bloodlust. Mari’s parents, John (Gaylord St. James, of Deadly Weapons and Horn-a-Plenty) and Estelle (Cynthia Carr), are a bit worried about the girls’ plans. Like many suburbanites, they harbor a deep-seated dread of the city after dark, and Estelle has heard that the club where the band is playing is in a bad neighborhood. Mari’s parents also don’t like Phyllis; they think she’s a bad influence on their daughter, and Phyllis surely doesn’t help the cause any by informing the Collingwoods that her parents are in the iron and steel business— “Yeah, my mom irons and my dad steals.”

In point of fact, the Collingwoods’ worries come nowhere close to doing justice to the situation. Once in the city, Mari and Phyllis attempt to buy some pot, and manage to get themselves into more trouble than either they or their parents could ever have imagined. There’s been a prison break, you see. A pair of murderers, rapists, and all-around creeps named Krug Stillo (David Hess, who would spend the next several years appearing in one ripoff of this movie after another— look for him in Hitch-Hike and House on the Edge of the Park) and Fred “Weasel” Podowski (heroically prolific porn director Fred J. Lincoln, whose other onscreen appearances include Fleshpot on 42nd Street and— inevitably— The Last Whorehouse on the Left) have broken loose with the aid of Stillo’s smack-addict son (Marc Sheffler) and lunatic, bisexual girlfriend, Sadie (Jeramie Rain, of The Abductors— and something tells me it’s no coincidence that her character goes by the same name that one of the Manson girls favored as an alias). Sadie’s contribution, in case you were wondering, was to kick a German shepherd to death when the prison guards set the dogs on the escapees, and Junior Stillo’s dope habit was a little present from his old man. So: Not nice people. Anyway, when Mari and Phyllis go looking to score, they have the wretched luck to pick Junior (whom they meet at random out on the street) as the prospective supplier of their grass. Junior says he’s got an ounce of prime Colombian up in his apartment, and invites the girls to come on up. From the moment Mari and Phyllis walk in the door, they can pretty much consider themselves kidnapped, and it’s only going to get worse for them from there.

The girls spend the ride out of the city in the trunk of the getaway car, and since they both get loaded in unconscious, it seems safe to say that some pretty awful stuff has already happened to them by that point. Mari’s parents, meanwhile, are really starting to wonder what the hell has become of her. Estelle calls the club and is informed that the show last night ended at 2:00 am— plenty long enough ago, in other words, for the girls to have made it home by now. As morning drags on into afternoon, the Collingwoods become sufficiently freaked out to call the cops and report their daughter missing. Unfortunately, the sheriff (Marshall Ankers) and his deputy (Martin Cove, from Death Race 2000 and Blood Tide) will spend the rest of the movie proving themselves to be the biggest tools in Connecticut (or northern New York State, or wherever the hell this is supposed to be). In fact, Sheriff Shit-for-Brains manages not to nab the bad guys even when Junior’s Cadillac breaks down right in front of the Collingwood house— while he and Deputy Dumb-Fuck are actually on the premises conferring with John and Estelle!!!!

Their escape attempt having hit a snag with the breakdown, the Stillo gang decide to have some fun for a while. Krug and Weasel drag Mari and Phyllis from the trunk, and march them down into the woods across the street; Mari naturally recognizes her surroundings, but there isn’t a whole lot she can do with that information just now. After they’re all well away from the road, Krug and his pals set their minds to thinking up ever more unpleasant things to do to their captives, culminating in the brutal slaying of both girls. Once the deed is done, however, the Stillo gang unwittingly do something just as disastrous for them as Phyllis’s bid to buy drugs from Junior was for her and Mari: they go to stay the night at the Collingwood place under the pretense that they’re traveling salesmen who have encountered car trouble. And while they’re under their victim’s very roof, they accidentally drop enough hints that John and Estelle are able to figure out exactly who they are and exactly what they’ve done. The result plays almost as a dress rehearsal for The Hills Have Eyes, as the good and wholesome middle-aged suburbanites rise (or sink) to the occasion, and show that they are more than capable of matching their guests’ savagery.

In Screams and Nightmares: The Films of Wes Craven, the director is quoted describing an encounter with a group of documentarians which he believes influenced his approach to the violence in The Last House on the Left: “They were a very tough lot, and they used to say to each other, ‘What if you were watching a mother dying on the sidewalk, would you go to help her?’ They said, ‘No, keep filming.’ So the thing was that you do not blink, you do not look away, because then you become television, then you become American commercial movies.” Though I am decidedly in the minority in saying so, I believe it is precisely that unflinching documentary sensibility that Wes Craven failed to achieve in The Last House on the Left, turning what should have been one of the most stomach-churning horror films of its age into just another crummy exploitation flick. There’s a lot of stuff here that ought to work. Krug’s inventiveness in humiliating and tormenting the girls outstrips nearly anything you’ll find in any other horror movie. The scene in which he and his friends force Mari and Phyllis to have sex with each other in the woods is— commendably— just about the least erotic bit of cinematic lesbianism I’ve ever seen. The rape scenes are similarly devoid of anything remotely salacious or arousing, and if it weren’t for a couple of things which I’ll be getting to in a moment, the final fates of the captive girls would be almost impossible to watch. Best of all, Craven spends a significant amount of time in the aftermath of the killings demonstrating— with scarcely a word of dialogue— that the viciousness of the crime has surpassed even the Stillo gang’s tolerances for wanton cruelty. Though none of them ever acknowledges it, it’s obvious that all four participants in the double murder are thoroughly disgusted with themselves when it’s all over. The trouble is that, regardless of his professed aims, Craven does blink, does look away. The torture of the girls is broken up into segments, as it would be in any conventional film in which a gang of bloodthirsty killers are hunted by the police, and those interludes are spent on what almost has to be the single most offensive comic-relief subplot in existence. The sheriff and the deputy are portrayed throughout as a couple of pin-headed boobs, and their failure to crack the case in time to save Mari and Phyllis comes not through any honest means, but through a succession of zany blunders and mishaps such as might befall Jackie Gleason and Mike Henry in a Smokey and the Bandit movie. We’ll see Krug commanding Phyllis to piss her pants, then cut to the police car shuddering to a halt because Deputy Dumb-Fuck forgot to check the gas tank before speeding off toward the Collingwood house. We’ll watch Krug rape Mari after carving his name into her chest with Weasel’s switchblade, then skip over to Sheriff Shit-for-Brains as he negotiates fruitlessly for a ride on the chicken-laden pickup truck which a toothless old black lady was driving to the farmer’s market. The oscillation is jarring from the first, and eventually I found myself not bothering to become invested in the girls’ suffering, because I knew the Komic Relief Kops would just come back to fuck it all up again in a minute or two. It is thus that The Last House on the Left becomes boring against all odds, by convincing the audience that there just isn’t any point in becoming horrified.

The Last House on the Left also suffers from having one of the most ill-considered soundtracks imaginable. This combination of overblown acid-rock and goofball hippy honky-tonk would sit uneasily upon any horror movie. In a film like this one, which aims for total immersion in the grisliest possible scenario, it’s something close to the perfect self-sabotage. Even worse for the purposes of creating a documentary atmosphere, nearly all of that out-of-place music was composed specifically for The Last House on the Left, with lyrics that explicitly refer to the action onscreen. I can think of no surer way to “become television… become American commercial movies” than that! The tragic thing is that the movie The Last House on the Left was supposed to be is in there somewhere. Watch it with the sound off and hit “fast forward” the moment you see either of the cops show their faces, and you might actually have approximately the experience Craven says he intended.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal salute to the Video Nasties. Click the banner below to see just how much nastiness my colleagues and I could take.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact