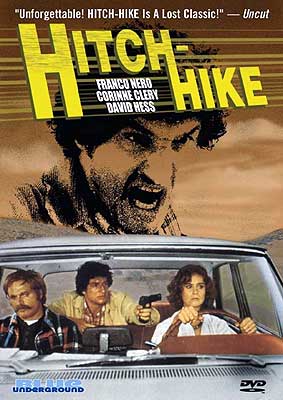

Hitch-Hike / Hitchhike: Last House on the Left / Death Drive / The Naked Prey / Autostop Rosso Sangue (1977/1978) ***

Hitch-Hike / Hitchhike: Last House on the Left / Death Drive / The Naked Prey / Autostop Rosso Sangue (1977/1978) ***

I think we can all agree that ripping off The Last House on the Left is one of the sleaziest things you can do as a filmmaker. I mean, it’s one thing to be vile, but quite another to hop aboard a bandwagon of vileness. So imagine my surprise as I watched the opening credits to Hitch-Hike, and one major name after another from the Italian movie industry flashed across the screen: Franco Nero, Ennio Moricone, Pasquale Campanile. What the hell were those people doing in a movie like this?! Well, as I was soon to learn, Hitch-Hike is no ordinary Last House on the Left copy. It’s smarter, more complex, more psychologically astute, and as the involvement of all those spaghetti-cinema A-listers implies, it’s altogether better made than any other such film I’ve seen. None of which is to say that it isn’t still sleazy as hell…

The marriage of Walter (Nero, of The Visitor and The Wild, Wild Planet) and Eve (Corinne Clery, from The Story of O and Striptease) Mancini has not been a happy one. Walter is a reporter, but he hasn’t broken a significant story in years. Eve blames his constant, nigh-heroic drinking for that, but Walter blames her. You see, Eve’s father owns the paper he writes for. The other guys in the newsroom chalk up all his early successes to favoritism, and now he finds himself frozen out of all the assignments worth having. So why shouldn’t he drink? Like a lot of B-movie couples in their position, the Mancinis have inexplicably gotten it into their heads that the way to save their marriage is to go on an arduous vacation together, renting a car and a trailer for a road trip across the Southwestern United States. The venture is already going about as well as these things usually do, for our introduction to the Mancinis comes while Walter is hunting stag, but lining up Eve in his crosshairs instead. He doesn’t shoot her, but he also doesn’t hesitate to tell her that he was thinking about it later.

We spend the next reel or two watching the couple alternately being shitty to each other (usually at Walter’s instigation, to be sure, but Eve gives as good as she gets when provoked) and hate-fucking. Then Eve insists upon pulling over to help out a stranded motorist, and the whole dynamic of the film changes. The guy with the broken-down Pontiac calls himself Adam Kovitz (David Hess, from Body Count and House on the Edge of the Park), and he seems nice enough at first. However, that’s only because the Mancinis never get close enough to his car to spot the man slumped over in the driver’s seat with a bullet hole in his head. Kovitz has had a busy day. First, he and three buddies of his broke out of the high-security mental hospital where they were all confined. Then they robbed the payroll office of the petroleum company Gastech, and made off with $2 million. Next, Kovitz double crossed his accomplices, making sure that he was in the getaway car carrying the loot (they had used two so as to complicate the problem of catching them) and shooting his erstwhile partner as soon as they were sufficiently far away from both the scene of the crime and the other two robbers. Now he’s got all the miles between the Las Vegas hinterland and the Mexican border in which amuse himself by tormenting his unwilling chauffeurs. Better still that one of the hostages is a beautiful woman…

I have to wonder how common was the knowledge of Rabid Dogs within the Italian movie industry in 1977. Obviously Pasquale Campanile couldn’t have seen it, but might he (or somebody else involved on the creative side of the production) have heard through the grapevine that Mario Bava had been working on a film in which gangsters fleeing the scene of a payroll heist force hostages to drive getaway for them with Last House on the Left-ish results? Granted, the premise isn’t so difficult to arrive at, and Hitch-Hike does claim to be based on Peter Kane’s novel, The Violence and the Fury, but some points of resemblance are downright uncanny. The ending especially puts me in mind of Rabid Dogs, since Walter, like the latter movie’s Riccardo, turns out to have some impressively dirty tricks up his sleeve. And I certainly have no trouble imagining producers Mario Montanari and Bruno Turchetto learning about the Bava movie’s legal and financial woes, and deciding that somebody needed to be making money off of such a good idea.

That said, Hitch-Hike diverges sharply from Rabid Dogs after about the 45-minute mark. That’s because Kovitz’s surviving accomplices, Hawk (A Spiral of Mist’s Carlo Puri) and Oaks (Gianni Loffredo, from Great White and 1990: The Bronx Warriors), catch up to him and his hostages, not in the best of moods. At first it even looks like they kill Kovitz, but it quickly becomes apparent that the Mancinis are going to be caught in a running battle among the estranged criminals. Kovitz’s return to action is a doozy, too, briefly transforming Hitch-Hike into, of all things, a serviceable counterfeit of Duel. The threats posed by Adam on the one hand and his rivals on the other are differentiated in an intriguing way. In contrast to the randy Kovitz, constantly menacing Eve with rape and hammering on all of Walter’s macho insecurities, Hawk and Oaks are gay. In fact, Oaks took part in the heist because of the chance it seemed to afford for him to ditch his wife and start a new life somewhere with Hawk. With them, the issue isn’t sexual violence, but Hawk’s instability. Adam’s is a calculating sort of evil, his desire to play all the angles to the utmost so great that he even tries to interest Walter in a book deal, but Hawk is just plain kill-crazy, with nothing to restrain him save the somewhat cooler head and sounder judgement of Oaks.

All that makes Hitch-Hike certainly the busiest and probably the least predictable of the spawn of Last House on the Left. Indeed, it’s got so much going on as to require a whole fourth act that I can’t talk about at all without blowing the resolution to the three-cornered conflict sketched out above. There’s some really sharp character writing at work, too, which steers the story clear of what frequently look at first like clichéd situations. If you watch as many Italian exploitation movies as I do, that cliché avoidance is downright shocking, especially since Hitch-Hike is so obviously derivative of a better-known movie. Adam Kovitz isn’t just Krug Stillo with the serial number filed off, despite being a functionally equivalent character played by the same actor. The third-act turnabout, in which the hostages go on the attack at last, is played for completely different effect from the norm in these pictures, delivering a short, sharp shock instead of the expected leisurely wallow in bloodthirsty vindictiveness. Nor do the protagonists’ sufferings mean what they usually do, for Hitch-Hike breaks with one of the most basic clichés of all, not just within its subgenre, but within the whole of 20th-century fiction. Adversity does not re-forge the Mancinis’ acrimonious marriage into something stronger and finer than before, but rather brings about its final collapse— and it certainly doesn’t teach either of the bickering spouses to be better people.

Hitch-Hike is also far more visually attractive a movie than I anticipated. The look of the film owes a great deal to spaghetti Westerns, so much so that I was astonished to find not a single recognizable Western title on either Campanile’s resumé or those of Hitch-Hike’s two cinematographers. Although this movie takes place mostly inside a car, and therefore deals intensively in claustrophobia (another thing it has in common with Rabid Dogs), it nevertheless heavily emphasizes the breadth and openness of the surrounding natural environment— the wide, stark horizons, the vast expanses of dry scrubland. The contrast between the two is effectively unsettling as well as aesthetically admirable. Whoever did the location scouting deserved a nice bonus, too; the whole shoot was conducted in Italy, but damned if this scenery isn’t a plausible stand-in for the merely semi-arid sections of the American Southwest. The cinematography in general is exceptionally good for a film of this type, with lots of arresting compositions and some really clever deep-focus tricks to put across in a single shot information that would otherwise require a whole series of cuts. The latter is especially beneficial during scenes that derive suspense from the physical separation between characters. All in all, Hitch-Hike demonstrates that even in Italy, there’s much to be said for occasionally turning highly regarded artists and artisans loose in disreputable genres, provided they come prepared to treat the material with a modicum of respect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact