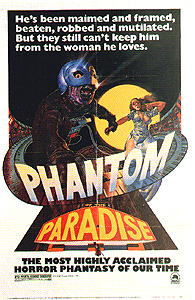

The Phantom of the Paradise (1974) ***½

The Phantom of the Paradise (1974) ***½

These days, Brian DePalma is best known as Hollywood’s foremost Hitchcock wannabe of the 70’s and 80’s— either that or as the self-congratulating asshole responsible for Mission to Mars. But right before he became a big star on the strength of movies like Carrie and Dressed to Kill, he directed The Phantom of the Paradise, a completely whacked-out amalgam of Faust, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the crappy 1943 remake of The Phantom of the Opera that truly must be seen to be fully believed.

As a voice-over intro by Rod Serling explains (Jesus— we’ve got “The Twilight Zone” in here too!), the biggest name in rock as of 1974 is a man known only as Swan (Paul Williams, from Battle for the Planet of the Apes). Apparently he was once a huge singing sensation himself, but these days, he’s content to play more of a Phil Spector sort of role, manufacturing new stars to cast reflections of his own former glory. For many years, Swan has dreamed of opening a concert hall, to be called “the Paradise,” that will simultaneously serve as a venue for the performances of his various proteges, and as a monument to his own immense ego, but he has been putting this scheme off for want of the perfect opening-night music. This movie, Serling explains to us, is the story of that music— “of the man who wrote it, of the girl who sang it, and of the monster who stole it.”

Let’s start with “the man who wrote it.” Winslow Leach (William Finley, of Sisters and Eaten Alive) is a composer and piano-player who has devoted his life to an extremely odd project— he’s working on a pop-rock version of Faust. Actually, this might not have been as strange in 1974 as it seems today. The early 70’s, after all, were the arguably the most pretentious period in the history of American pop music, an era when musicians and critics alike were going to ridiculous lengths to demonstrate that rock had become every bit as “mature” and “sophisticated” as jazz or even classical music. In truth, all they demonstrated was that there were vistas of suck beyond the horizon the likes of which even the most incompetent 60’s acid casualties had never dreamed of. The 70’s were a time of 20-minutes songs and electric violins; a time when rock and rollers around the world forsook the visceral directness that lay at the core of their calling in favor of empty, flatulent theatricality; a time when hundreds of thousands of people thought it was a great idea to create music that only made sense if you were zonked out of your mind on hallucinogens. It was in the 70’s that the notion of the “rock opera” billowed up like a plume of acrid smoke from the blazing sulfur-pits of Hell, and with that in mind, maybe Winslow Leach and his rock cantata make a twisted kind of sense. But unfortunately for Leach, the man is pretty much the diametric opposite of the rock star awaiting discovery. He’s skinny, gawky, unattractive, and he wears glasses with lenses easily half an inch thick. Winslow Leach has absolutely no stage presence, and no amount of coaching or mentorship will ever impart it to him. As such, his visions of personal stardom are pretty much hopeless.

This is where Swan comes into the picture. Swan hears Winslow performing a section of his cantata in between sets at a concert the impresario set up for his current pet band, the Juicy Fruits, and he immediately realizes that this is the music he’s been looking for to inaugurate the Paradise. The only problem is Winslow himself— this man obviously will not do as an opening-night headliner. Swan’s initial idea seems to be to recruit Leach as a songwriter for his Death Records label, but Winslow is adamant that his masterwork is to be performed by no one but him. Faced with this setback, Swan’s A&R man, Philbin (George Memmoli), simply cons Winslow into “lending” him what proves to be the only extant copy of the Faust cantata, offering the story that Swan will soon be getting back to him with an offer for a record deal.

Yeah, and if you believe that... Two months later, Winslow still hasn’t heard a goddamned thing from either Swan or Philbin. When he stops in at the offices of Death Records to see what’s up, the receptionist turns up a card in his file that identifies him as “never to be seen,” and orders security to throw him out. Winslow gets no warmer a reception at Swan’s mansion, but he does discover, in the course of a futile attempt to see Swan at home, that the double-dealing scumbag is auditioning literally hundreds of girls for a backup chorus— girls who are rehearsing from copies of his sheet music! One of these hopefuls— Phoenix (Jessica Harper, from Shock Treatment and Suspiria) is her name— is the only genuinely friendly person Winslow encounters during the whole sorry debacle, and the only one who seems to believe that he really wrote the material she’s been singing. Eventually, Winslow’s repeated attempts to get through to Swan lead to him being beaten up by Philbin’s goons and arrested on trumped-up drug charges by a pair of corrupt cops who are on the take from the producer. Winslow ends up incarcerated in Sing Sing, where he spends the next couple of years “voluntarily” participating in medical experiments financed by the Swan Foundation. (These experiments, bizarrely enough, entail having all of his teeth pulled and replaced with stainless steel dentures.) Then one day, when Winslow hears the Juicy Fruits playing one of his pilfered songs on the radio, he snaps and breaks out of prison. Once on the outside, he heads straight for Death Records, which he intends to destroy by setting a bomb in the record-pressing plant in the basement. He almost succeeds, too, before one of the security guards catches him, and in the ensuing struggle, Winslow is shot and knocked into one of the record presses. Bleeding heavily from the bullet wound, and with half his face burned away by molten vinyl, Winslow staggers off and plunges into the East River, never to be seen again.

That’s how the papers tell it, anyway. Actually, Winslow survives his ordeal, and when work is completed on the Paradise, he sneaks in, steals a suitably outlandish costume (complete with mask) from the wardrobe department, and sets about haunting his nemesis’s club. Now so far, we’ve been following the plot from the 1943 Phantom of the Opera fairly closely, but all that’s about to change. Swan figures out very quickly the secret identity of the masked, cloaked, and leather-clad vandal who’s been sneaking around backstage at the Paradise, and when the two enemies meet face to face, he has an interesting proposal to make. Swan offers Winslow a songwriting contract, essentially making him co-producer of the Paradise’s upcoming presentation of “Swan’s Faust.” Winslow will get to choose the lead performers, and will have complete control over the creative side of the production. And just to sweeten the deal, Swan will even set Winslow up with an electronic voice synthesizer to compensate for the damage the record press did to his vocal cords. Of course, those of you who know anything about the way the recording industry works will be very suspicious of Swan and his contract, even before Winslow discovers clauses like “all items that are excluded shall be deemed included,” and Swan demands that he sign the document in blood.

So somehow, we’ve left The Phantom of the Opera behind, and wandered into Faust territory. We’ll be teaming up with Gaston Leroux again soon enough, but henceforth, it’s Goethe who’s in the driver’s seat. Then, when Winslow learns that Swan, too, is “under contract,” Oscar Wilde will come along for the ride, as it is revealed that Swan, when he was a rising star some 25 years ago, traded his soul to the Devil for eternal youth and worldly success and received in exchange a videotape of himself which now does all his aging for him. At the center of the coming conflict is Phoenix, who plays Christine to Winslow’s Eric, and whom Swan wants to sign a contract of her own.

When I first saw The Phantom of the Paradise, I don’t know, maybe 18 years ago, I mainly just liked it for the character design of the Phantom himself. The black leather, the cape, the one good eye goggling out from behind the silver hawk-face mask, the creepy electronic voice, and those weird steel teeth still look awfully cool to me, but now I’m in a position to catch so much more of what’s going on. As a musician myself, I’ve had good reason during the last decade or so to learn how the music industry really does business, and knowing what I know now makes The Phantom of the Paradise blackly hilarious in a way that I never would have appreciated even as recently as my late teens. The standard recording contract really does favor the record label to such a ludicrous extreme that the artist signing it might just as well have sold his or her soul to Satan, and even for many big stars, the long-term outcome proves scarcely less disastrous. Meanwhile, Brian DePalma does a brilliant job of poking fun at the overblown mid-70’s rock establishment; I came away from this movie with the distinct impression that his contempt for that scene rivals even my own. From the Juicy Fruits’ fad-driven evolution into first the Beach Bums and then the Kiss-like Undead to such minor details as Swan protege Beef (Gerrit Graham, of Demon Seed and C.H.U.D. II: Bud the C.H.U.D.) dismissing Philbin’s contention that the Phantom is just a figment of his drug-addled imagination (“Hey, man— you just pass the stuff out; I take it! I know drug reality, and that was real reality!”), virtually every satiric salvo DePalma launches scores a direct hit. And while he’s at it, DePalma even finds time to toss in a Hitchcock riff that hints at the course of his career as a director over the next ten years. The only thing hindering The Phantom of the Paradise (apart from the fact that some of the humor is maybe just a little too broad) is the music. This is a movie about a rock club, after all, and that means we’re going to hear a whole lot of music. And because this is a movie about a mid-70’s blowhard-rock club, that means we’re going to hear a whole lot of really shitty music. If you still have the occasional nightmare about the Electric Light Orchestra, then you might have a hard time getting through The Phantom of the Paradise. But if you’re man enough to stand fast in the face of Beef in concert, then this can be an extremely rewarding film. In any event, it’s a hell of a lot better than The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact