Children of Men (2006) ***½

Children of Men (2006) ***½

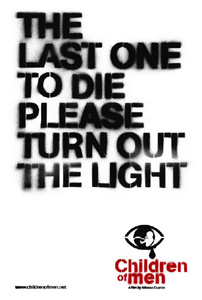

I love an eccentric apocalypse. Nuclear war, pandemic disease, and the dead rising from their graves to slaughter and consume the living are all classics— and justly so— but from time to time, I like to see the world end in some really off-the-wall way. Happily, oddball apocalypses have been appearing with ever greater frequency as the Cold War recedes into the past, and the metaphors associated with it become increasingly outmoded. Children of Men features one of the oddest yet. Apparently taking as its starting point the disquieting demographic trend whereby most of the developed world has been breeding at well below replacement rate for some twenty years, it posits a complete end to human fertility, and imagines the cataclysmically inappropriate reactions that we might make to a situation in which there was literally no future for our species.

The last child on Earth, “Baby Diego” Ricardo, was born in 2009 in Mendoza, Argentina. It is now 2027, and the world’s youngest human was just stabbed to death in a bar fight in Buenos Aires. Order is falling to pieces just about everywhere, as humanity sinks into nihilism and despair. In Britain, where the surrounding sea seems to promise the possibility of quarantine against an increasingly chaotic outside world, the government has spent the last eight years trying to round up and eject all the foreign nationals in the Isles, regardless of whether they came as refugees from newly failed states or had dwelt there legally and peacefully for much of their lives. Trains and buses full of “fugees” bound for coastal deportation camps have become a regular part of the scenery, and entire towns like Bexhill-on-Sea have started looking alarmingly like the Warsaw Ghetto in 1939. This draconian policy has given rise to an occasionally terroristic opposition front, known for some opaque reason as the Fishes. (An amusing detail: native Brits who join or sympathize with the Fishes are colloquially known as Cod.) Together with a panoply of religiously-themed protest movements— the Renouncers, the Repenters, Islamists of roughly the sort that have been helping to keep the Middle East backward and benighted since Muhammad ibn Saud struck his Faustian pact with Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab in 1744— the Fishes seem to be better at giving the government a bogeyman with which to scare the masses into cheering for oppression than they are at actually advancing their cause, but try telling them that.

Anyway, TV journalist Theo Faron (Clive Owen) becomes more directly embroiled in the issues of the day than he is accustomed to being when he is abducted on the street by Luke (Serenity’s Chiwetel Ejiofor) and Rado (Michael Klesic), a pair of Fish operatives, and transported to their local headquarters in the back of a van. To Faron’s considerable astonishment, the Fish leader who talks to him once Rado pulls the sack off of his head is Julian (Julianne Moore, of Tales from the Dark Side: The Movie and The Lost World: Jurassic Park), an ex-wife or ex-girlfriend (it’s never quite clear which) whom he hasn’t seen in some twenty years. Both had been college radicals, and although their relationship collapsed long ago (something to do with a dead toddler), Julian is confident that she can still influence Theo to do her a little favor. There’s a girl, see— a fugee— and it’s vitally important for some reason that she make it to a Fish safehouse out in the countryside. In order to do that, she’ll need valid identity papers and travel visas, which Faron has the proper connections to obtain. Julian won’t say what any of this is about, but there’ll be £5000 in it for Theo if he helps. Theo says he’ll think about it, and Luke drives him back to the city.

He doesn’t have to think too long. Nevermind leftover radical sympathies— Theo has gambling debts that need paying! The trouble is, the only travel papers he can get from his hookup are for a couple on the road together, so Faron is going to have to accompany this mysterious girl to her destination, posing as her husband. That works for Julian, and within a few days, Theo is squeezing into an itty-bitty car with her, Luke, and two other parties: Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), the West Indian refugee on whose behalf the whole adventure has been orchestrated, and a matronly middle-aged woman named Miriam (Pam Ferris), who is apparently her designated handler. Things go horribly wrong almost immediately. No sooner have Luke and company driven into what looks like the middle of nowhere than they fall into a massive ambush organized by who knows whom, and Julian is shot through the throat by a man on a motorcycle while they scramble to make their escape. Then they get pulled over by the police, and Luke guns down two cops before they’ve had a chance to do anything but ask to see his ID. By the time the Fish safehouse comes into view, it’s pretty well obvious that Kee is no ordinary refugee. Yeah— serious understatement, that. Kee is about eight months pregnant, making her the biggest news to hit Planet Earth in eighteen years.

So, making sure we’re all on the same page here, the expectant mother of the Only Baby Anywhere is an illegal alien, liable to inhumane deportation for the good of king and country. Hard to imagine a situation more embarrassing to officialdom than that, isn’t it? Should the government get its hands on Kee, the best-case scenario has the girl sequestered in a lab somewhere until she gives birth, after which she gets packed off to Calais, and the 10 Downing Street types find some nice, respectable, middle-class couple to pass off as the parents for the press. Worst-case scenario, some dumbfuck bobby arrests Kee without ever registering the significance of the humongous bulge in her belly, and she winds up riding the Fatal Miscarriage Express to Bexhill-on-Sea. Then there’s the whole range of possibilities in between, involving a lifetime of medical experiments and/or forced breeding. Clearly the girl needs to be kept below the government’s notice, but what to do with her beyond that? Julian and Miriam had intended to hand Kee over to an international agency of doctors and scientists called the Human Project, which has been researching the thus far intractable problem of mass infertility. Most people regard the Human Project as nothing more than an urban legend, but Julian had managed to get in touch with them shortly after Miriam brought Kee to her. The plan was to deliver Kee to a disguised Human Project hospital ship which operates in the English Channel on a more or less regular schedule, and both Miriam and the cargo herself still like that idea. Luke, however, contends that some rethinking is in order. Ostensibly, he fears that the ambush that afternoon indicates that somebody outside the Fish movement has gotten wind of Kee’s condition, and wants her for their own mysterious and surely nefarious purposes. But the truth is that Rado set that ambush at Luke’s instigation, and that the Fishes have a nefarious purpose of their own. A fertile fugee is as convenient for the immigrants’ rights movement as it is inconvenient for the government, and Luke wants to capitalize on Kee’s baby to lend a messianic flavor to the nationwide uprising his agents have been trying to seed for who knows how long. Naturally, no one has bothered to ask Kee whether she minds having her pregnancy turned into a political talisman, and Rado killed Julian deliberately because she had been staunchly opposed to any such thing.

There’s one thing Luke and Rado didn’t count on, though. They weren’t expecting Theo to stick around after delivering Kee to the safehouse, and they certainly never considered the possibility that he would overhear them discussing their treachery against Julian. The moment Faron gets wise to their scheme, he grabs Kee and Miriam, steals a car from the Fish motor pool, and heads for the hills— “the hills” being the secret woodland hideaway of Theo’s most eccentric friend, another old radical by the name of Jasper (Michael Caine, from Jaws: The Revenge and The Hand, who really seems to be settling into his role as an eminence gris of quirky but well-funded genre films). Jasper is a pretty well-connected man, yet he’s somehow managed to avoid unwanted attention from the kind of people who like to make trouble for elderly hippies. He’s also both utterly dependable and a devious bastard, so if anybody is going to figure out a way to keep Kee out of harm’s way while smuggling her onto that Human Project hospital ship, it’ll probably be him. Jasper does not disappoint. A buddy of his named Syd (Session 9’s Peter Mullan) is a slightly crooked cop, and with Syd’s help, Jasper concocts a brilliantly counterintuitive plan to escape from England by sneaking Kee into the very deportation camp where she would be sent if the cops ever caught her, which is conveniently sited along the vessel’s patrol route. Unfortunately, while that might bamboozle the authorities effectively enough, the Fishes are just as resourceful as the government in their way, and their way includes being hip to things like suborned policemen and secret compounds in the woods.

All things considered, it’s a little strange that mopey and glum is a mood so rarely encountered in movies about the collapse of modern civilization. I would expect most people to spend a lot of their time in various shades of blue funk if the world ever got to be as screwed up as what you see in the average post-apocalypse flick, myself! Consequently, I consider Children of Men’s greatest strength to be the emphasis it places on conveying what a fucking depressing prospect the end of the world would really be. Plenty of movies focus on the horror of a return to barbarism, and plenty more cast a wearily cynical eye on the likelihood that even worldwide destruction won’t suffice to teach mankind its lesson. A few even contemplate the mind-wrecking loneliness that would surely afflict any isolated survivors of some massive and sudden global catastrophe. But apart from On the Beach, Children of Men is the only film I can think of that relates to the demise of our species primarily as something bitterly, hideously sad. Like that lamentably little-recalled late-50’s nuke-opera, Children of Men sets up a situation in which everything everyone does is overshadowed by the nearly certain knowledge that those people who are alive today are the last of their kind who will ever exist. Everything interesting and important and inspiring that humans have ever done, every invention, every discovery, every work of genius and thing of beauty— it’s all about to be over, and there will be absolutely no one left to care that any of it happened in the first place. True, the end of the humanity also means the end of human viciousness and stupidity, but that isn’t nearly bright enough a silver lining to make the cloud of extinction bearable except to the most committed of misanthropes. And though there are obviously some pretty committed misanthropes in Children of Men’s world, we don’t spend much time in their company. The folks we deal with are the ones whom grief has driven to bloody nihilism, and the ones stubbornly trying to make one last bit of difference in the world while there are still a few years left before the very concept of making a difference is rendered permanently irrelevant. There are also a few— most notably Luke and Rado— who sort of fall into both categories at the same time.

Given the morose tone of the film, it is only to be expected that Children of Men unfolds at a much more leisurely pace than most We Have Seen the Future, and It Sucks movies. I expect some will have a problem with that, but I personally did not. In fact, I like how Children of Men manages to remain weirdly low-key even after Luke’s longed-for uprising begins, and the army descends upon Bexhill-on-Sea with a column of tanks and armored cars. It isn’t Theo’s fight, or Kee’s; in fact, participating in a revolution— on either side— is that last thing either character wants. Theo isn’t that kind of hero, and Kee has no interest in being a heroine at all. She just wants to keep her baby safe, he just wants to make sure she has a fair chance to do it, and the two of them deal with the battle erupting around them as essentially an obstacle course to be negotiated by stealth. Writer/director Alfonso Cuarón is therefore to be commended for keeping the focus on their escape attempt, rather than allowing himself to get sidetracked by the big, exciting final-act shoot-‘em-up. He stays true to the spirit of the story, even at the point when the temptation to stray is strongest. Ideally, that wouldn’t be something deserving of special praise, but a tour through the sci-fi section at your local video store will show how far from ideal the state of the genre has been during this decade, so praise it specially I shall.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact