On the Beach (1959) ***˝

On the Beach (1959) ***˝

Given how often the world ended on film during the 1950’s, and given also how real the possibility of imminent nuclear apocalypse was in those days, two things become very conspicuous by their scarcity. First, although alien invasions, planets on collision courses, and monstrous personifications of the atom bomb were thick on the ground, there were relatively few movies willing to call a spade a spade by calling a nuke a nuke. Secondly, there was, for most of the decade, a pronounced shortage of serious, mature movies with apocalyptic themes. And what is most interesting, it can be taken as a rule of thumb that the more directly a 1950’s end-of-the-world movie addresses the prospect of nuclear annihilation, the less serious and mature it is likely to be. Compare Rocket Attack U.S.A. with Godzilla: King of the Monsters and The World, the Flesh, and the Devil to get some idea of what I mean. The former film (technically a 60’s movie, although its heart belongs wholly to the previous decade) explicitly invokes the specter of atomic war between the United States and the Soviet Union, and it’s some of the purest schlock imaginable. Godzilla trades on the fears raised by its era’s nuclear standoff, and handles them with the utmost sobriety, but it cloaks the bomb in a heavy layer of sensational allegorical fantasy. As for The World, the Flesh, and the Devil, it’s the weightiest of the bunch, philosophically speaking, and by far the least sensationalistic, but it doesn’t even acknowledge the Cold War; the cloud of radioactive sodium dust that reduces the human population of the Earth to just a handful of scattered individuals starts off as somebody else’s doomsday weapon, and the superpowers aren’t so much as mentioned taking sides in the war that unleashes it. So having established the general rule, let us now turn our attention to its most glaring exception— Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach.

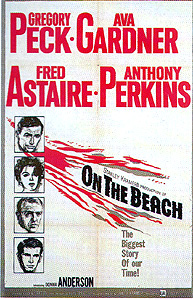

Kramer had a long history of making star-studded, middlebrow movies dramatizing a more or less liberal take on social and political issues, in which the big-name casts were used expressly as a means for securing studio support and audience attention in the face of what might otherwise have been considered radioactive subject matter. Perhaps the most obvious example of the technique (and the best illustration of its limits) is 1967’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, in which Sidney Poitier played opposite Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn as a successful, Yale-educated doctor whose one demerit as a suitor to the latter pair’s daughter is that he just happens to be black. In On the Beach, Kramer brought in Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, and even Fred Astaire (to say nothing of a pre-stardom Anthony Perkins) to meet the issue of nuclear war head-on, with no comforting layer of metaphor or double-talk to soften the blow. As generally happened with Kramer’s movies, the result was compromised to some extent by its own heavy-handedness, and the disproportionate concentration of star-power works to its detriment in some respects, but it is nevertheless a memorably affecting film.

As befits a truly post-apocalyptic movie, On the Beach begins with the final war already waged to something closely approaching mutual extermination. The whole Northern Hemisphere is now one vast, irradiated wasteland, but in the 1950’s, there was as yet nothing below the equator of any strategic significance for the balance of global military power. Consequently, Australia (and presumably South America and Subsaharan Africa as well) was spared direct attack, and so it is that what little remains of the American and British militaries is gathering there to figure out what comes next. For our purposes, the tattered scraps of NATO will be represented by Commander Dwight Towers (Gregory Peck, of Cape Fear and The Boys from Brazil) and the crew of the nuclear submarine USS Sawfish. The Sawfish puts into port in Melbourne, where Towers is to report to Admiral Bridie (John Tate, from Invasion and The Day of the Triffids), of the Royal Australian Navy. The commander will also be meeting up with Lieutenant Peter Holmes (Anthony Perkins, later of How Awful About Allan and Destroyer), who is to represent the RAN on a vital mission aboard the Sawfish. You see, although no bombs ever actually fell on Australia, the island continent is by no means safe from the effects of the war. The atmosphere above the Northern Hemisphere is thoroughly saturated with radioactive dust as a result of all that nuking, and the wind currents in the upper troposphere are carrying the fallout steadily southward. Bridie’s scientific adviser, Dr. Julian Osborne (Ghost Story’s Fred Astaire), calculates about five months’ respite before Australia is rendered just as uninhabitable as Russia or North America. However, another scientist by the name of Jorgensen (Peter Williams) has a slightly more hopeful hypothesis. Noting that the vast quantities of particulate matter blown up into the air have both drastically lowered the average temperature up north and greatly increased the potential for precipitation, Jorgensen thinks the fallout is being scrubbed from the atmosphere much faster than prewar models predicted. If Jorgensen is right, Australia or at least Antarctica may yet remain viable environments for human life. To test Jorgensen’s theory, Towers is to take Osborne and Holmes aboard his submarine, and sail as far north as possible so that the scientist can measure contamination levels at the surface, and thereby assemble some hard data on which to base a revised projection of the Southern Hemisphere’s fate.

It’s going to be a while, though, before any such undertaking can get underway. The Sawfish needs new fuel rods for its reactors, new provisions for its crew, and naturally whatever scientific instruments Osborne will require to make his observations. That’s a week or more worth of prep-work there, and in the meantime, Lieutenant Holmes thinks it would be a nice gesture to invite Commander Towers to spend a few days with him and his wife, Mary (Donna Anderson, of Sinderella and the Golden Bra). In fact, the Holmeses use Towers’s coming as an excuse to throw a party over the weeked, setting the commander up with their friend, Moira Davidson (The Sentinel’s Ava Gardner), the trashiest drunk slut of a single gal they know. Trust one navy man to know what another expects by way of hospitality, right? As it happens, Towers is more of a gentleman than anybody concerned expects, and he and Moira end up spending the hours after the party winds down discussing the ramifications of the apocalypse that each of them would most prefer not to have to face: Moira the fact that she’s caroused her life away without ever taking one second of it seriously, and Towers the certainty that the cloud of radioactive ash over New England contains a few trillion particles that used to be his wife and children. The relationship that develops between them during the days before the Sawfish sets sail will be defined to a greater extent than either one of them cares to admit by their mutual need to make up for what they’ve already lost. Mind you, Dwight and Moira aren’t the only ones in denial. Mary Holmes refuses even to talk about the recently concluded war, let alone to address such questions as what is to be done with her and Peter’s infant daughter once the fallout arrives. Some resistance to a serious discussion about infanticide is perhaps understandable, but Mary is being totally unrealistic in ducking the issue so completely. After all, the kid will be in no position to give herself one of the cyanide pills the government is now manufacturing in anticipation of the coming demand for mass self-euthanasia, and who the hell would wish death by radiation sickness on a baby? There’s an element of urgency in Peter’s determination to get his wife onboard the Terrible Truths bandwagon, too, for there’s every indication that the Sawfish will require about four months to complete its mission, leaving little or no lag-time between the sub’s return to Melbourne and the advent of the fallout cloud. And speaking of elements of urgency, the mission itself acquires a new one when Bridie cuts short Towers’s shore leave to alert him to something the submarine’s radio operator has just discovered. They make nothing like sense (suggesting that whoever’s behind them has little or no training in such things), but somebody is sending out a steady stream of telegraph signals from San Diego. Prospects for the future of the human race just got a whole lot better, didn’t they?

There are two main defects in On the Beach. First, the casting is rather strange, in that all the major Australian and British characters save Admiral Bridie and his secretary (Lola Brooks) are played by Americans, while all the Americans apart from Commander Towers are played by Aussies. It’s unobtrusive enough that you probably won’t realize at first why so much of the dialogue seems just the slightest bit off, but after a few bounces back and forth between the Holmes house and the Sawfish, it suddenly hits you that practically everybody has been speaking with the opposite accent all this time. On a related note, I have it on good authority that the myriad small ways in which Stanley Kramer has misread Australian culture become cumulatively intolerable if you actually hail from Down Under, although I personally didn’t pick up on them. The more serious problem is that Kramer loses all capacity for subtlety whenever he reaches a scene that bears directly on what he really wants to say, leading him to begin piling on jarring camera maneuvers and obnoxious musical stings. Take the sight that greets the Sawfish crew when they come to the surface in San Francisco Bay. The buildings are curiously intact (were neutron bombs even a theoretical concept yet in 1959?), but there is no sign of life whatsoever, not one person to be seen moving about on either the streets or the shoreline. It should be terribly unsettling (as indeed it was when Target Earth did much the same thing five years earlier), but Kramer suddenly starts directing in italics, and blows the somber mood completely. Similarly, the movie’s bludgeoning overuse of variations on “Waltzing Matilda” as background music is such that you’ll surely grow to loathe that melody even before the scene in which a mob of drunken fishermen apparently spend literally an entire day singing it at the top of their lungs. What makes this tendency toward directorial overkill especially annoying is how brilliantly Kramer succeeds on those occasions when he instead trusts his viewers’ intelligence, and lets the story carry its own freight.

For example, there’s a long, strange subplot about Julian Osborne entering a hastily organized road-race that ends up claiming the lives of several of its participants. Without any deliberate underscoring from Kramer, this sideline brings together all of the movie’s best insights about life in the shadow of inescapable final catastrophe. Osborne, who has never so much as drag-raced between traffic lights, buys a neighbor’s antique Ferrari, and signs up for the ramshackle grand prix secure in the knowledge that this is his very last chance ever to do something he’s always half-heartedly wanted to. The very fact of holding the race at all plays up the defiant insistence of the citizens of Melbourne to carry on their ordinary lives even in the face of extinction. The carnage that follows the starting gun (in addition to serving as a weird premonition of a few later end-of-the-world movies set in Australia) emphasizes the recklessness that impending doom can bring out in even the most sensible of people. It’s some of the most thought-provoking material to be found in any apocalypse movie of this vintage. The hunt for San Diego’s mysterious telegrapher is also blessedly free of unnecessary emphasis. And most importantly, Kramer, when he cares to use it, possesses great skill at investing mere conversation with tremendous dramatic weight. The best example is Peter Holmes’s last-ditch effort to open Mary’s eyes to the likelihood that their final obligation as parents will be to kill their daughter in order to spare her the lingering agony that will be her fate otherwise, but this is happily one category in which On the Beach offers substantially more successes than failures. There are uncomfortable nuances to the Dwight-Moira romance that go a long way toward absolving it of its more soap-opera-ish sins, as it gradually becomes apparent that this cresting-the-hill party-girl is, at the last, so desperate to have one meaningful relationship that she’s willing to pursue it even at the cost of subsuming her identity within the memory of Dwight’s dead family back home. Bridie and his secretary get a couple of potent scenes, as they haltingly realize that their shared, unswerving devotion to duty has left them with nobody but each other from whom to seek comfort as the end approaches. And rising nearly to the level of the Holmeses’ desperate baby-killing discussion, Dr. Osborne is asked several times to weigh in on the hows and whys of the apocalypse, exposing both his gnawing sense of responsibility as a nuclear physicist attached to the atom-bomb program (despite his own protestations that scientists like himself had also been the harshest critics of nuclear arms development) and his horrified suspicion that the war— which has left no one alive who really knows how it came about— might have begun with a malfunction in NATO’s electronic early-warning system. Since Osborne’s monologues speak most directly to On the Beach’s central message, it is well that they are among the film’s most affecting passages.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact