Godzilla: King of the Monsters / Gojira (1954/1956) ****

Godzilla: King of the Monsters / Gojira (1954/1956) ****

This is it, the film that initiated the main cycle of Japanese monster movies, or kaiju eiga. Probably still the best of its breed over half a century later, it is the film that defines the genre, and in most people’s eyes, it also defines the somewhat broader genre of 50’s-style monster rampage movies as a whole, regardless of their countries of origin. In the decades since its release, Godzilla: King of the Monsters/Gojira has taken on a truly mythic stature, transcending about as rigid a cultural boundary as you’re ever going to find in the developed world. And I’m not just talking about movie geeks, either; even if you’ve never heard of Gamera, Guilala, or even Mothra, you probably know who Godzilla is. One result of this is that the film almost seems like too big a subject for a mere movie review, and in fact entire books have been written about Godzilla, its sequels, its competitors and copycats, and the perverse way in which the movie gave rise to a phenomenon all out of proportion to the expectations and ambitions of the people who created it. But don’t you go thinking that’s going to stop me.

Gojira’s earliest origins, you see, will sound utterly typical to any follower of exploitation cinema; only as the writing hit its stride did it begin to develop into something truly unique. In 1952, a 20th-anniversary re-release of King Kong (okay, so they jumped the gun a little— it’s not like this was the first time something like that had happened in Hollywood) stunned the movie industry by out-grossing nearly every first-run film on the market. True to form, Hollywood swung into full frenzy, with everybody and his mother rushing to create a new giant-monster film to cash in on RKO’s unexpected success. Among the first of these movies to see release was The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), in which a made-up dinosaur called a Rhedosaurus terrorizes New York until it is destroyed by an injection of radioisotopes. The most significant thing about The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is the excuse that the filmmakers devised for bringing a dinosaur into the modern world— through a process that the film understandably spends little time explaining, the testing of American hydrogen bombs restores the creature to life. What all of this has to do with Gojira is that both of the aforementioned movies played in Japanese theaters as well as American. Nothing of the sort had appeared on the Japanese screen since the 30’s, and the resulting grosses swiftly set the cogs turning in the head of Toho Studios producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, who slapped together a pitch for the studio bigwigs on a plane-trip to Tokyo. That pitch must have been pretty impressive, because the studio not only green-lighted the film, but put the conspicuously talented director Ishiro Honda (not Inoshiro Honda, as he is so often credited in the American versions of his movies) and special effects godfather Eiji Tsubaraya in charge of the project, and commissioned Shigeru Kayama (then one of Japan’s biggest thriller writers) to pen the initial treatment.

The latter point hints at what made Japan’s answer to The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms different from the legions of America-made imitations. Toho was a big-time studio, able to throw big-time money at the production, but beyond that, the idea of an A-bomb-spawned monster had a unique resonance in the Japanese psyche, so that the people behind Gojira were also willing to make that kind of investment. We are talking, after all, about the only people in the world who have ever been on the receiving end of a nuclear attack, and whose land was, in the early 1950’s, still under American occupation and separated by only a relatively narrow stretch of sea from the nuclear-armed Soviet Union. I think it is thus fair to say that the Japanese experienced the nuclear nightmare of the Cold War in a way that no other nation on Earth did. In the Japanese context, a movie about an atom-powered monster meant far more than it could in the United States.

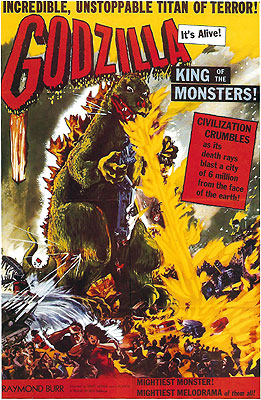

The fact that Americans were ill-equipped to take the idea behind Gojira as seriously as the Japanese can be seen from what happened to the movie when it was picked up for distribution over here— the first time such a thing had happened to a Japanese fantasy or science fiction film. To begin with, the movie was drastically re-edited in order to bring it more into line with distributor Joseph Levine’s understanding of American tastes, quickening the pace substantially. Levine furthermore shot a substantial amount of new footage with Canadian actor Raymond Burr, on the theory that US audiences would be unlikely to turn out for a picture with an all-Japanese cast. In addition, the movie, retitled Godzilla: King of the Monsters, was advertised here in much the same way as any cheap-jack monster flick of the day— the posters, lobby cards, trailers, etc. could all be described with a single word: lurid. It is thus very surprising to see how serious the American version really is. Even in its re-cut guise, it is clear from the very first frame that this is no standard-issue monster mash.

The US edit adds a short, commendably doom-laden prologue, in which American journalist Steve Martin (Burr, of course) comments in voiceover above a tracking shot of the flaming wreckage of Tokyo, but the real story begins at sea, with the destruction by an unexplained force of a Japanese fishing vessel. (This scene is a conscious echo of the “Fukuryu Maru Incident,” in which a Japanese tuna trawler blundered onto the site of an American H-bomb test. Most of the ship’s crew died of radiation poisoning or cancer, and there was a nation-wide recall of tuna in Japan.) Over the ensuing days, many more ships (seven in the American version, sixteen in the original) meet a similar fate; of those whose radio operators were able to get out a last message, all tell exactly the same story of a blinding flash followed by a great fireball erupting around the ship. The closest inhabited spot to the waters where the wrecks have occurred is Oto Island, and it is there as well that the only living witness to any of the sinkings can be found. Obviously no mystery of such deadly import can long escape media attention, and so it is that Oto quickly becomes host to a journalistic delegation from the mainland.

If you’re watching Gojira, the main figure among those reporters is named Hagiwara (The Secret of the Telegian’s Sachio Sakai); if you’re watching Godzilla: King of the Monsters, it’s the aforementioned Steve Martin, who hears of the story because his plane to Tokyo coincidentally flew over the site of the first shipwreck, at almost exactly the moment of the catastrophe, leading the local authorities question him and all the other passengers about anything they might have seen from their windows as they passed overhead. Martin is also portrayed as a close friend to one of the original major characters, a young scientist named Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata, who like most of the cast became a kaiju eiga regular as a result of his appearance here, showing up later in movies like Rodan and Varan the Unbelievable). Serizawa’s fiancee, Emiko Yamane (Momoko Kochi, of Half-Human and The Mysterians), is the daughter of renowned paleontologist and marine biologist Dr. Kyohei Yamane (Takashi Shimura, from Kwaidan and Gorath), who becomes involved after it is suggested that some sort of living thing might be to blame for the destruction. You see, the people of Oto Island have long believed the neighboring sea to be inhabited by a hideous monster of almost limitless destructive power, and the island elders contend that their monster— Godzilla— is behind the sinkings. Whatever Dr. Yamane, Hagiwara/Martin, and the various outsiders who accompany them may have thought about monsters before, this trip will make believers of them all. One night, while the island is lashed by a typhoon, something big pays a visit to Oto to add to the damage. It leaves a calling card in the form of huge footprints, about three feet deep and about as long as a respectably-sized car, and a trail of strontium-90 contamination. As Yamane begins to study these phenomena, one of the islanders starts ringing a big bell, apparently a signal to take to the hills for protection. Just about the time that the visitors begin to wonder what they might need protection from, Godzilla makes his first appearance, looming over a ridge of hills as he stomps back to the sea.

The inevitable bad-paleontology press conference follows once the characters have returned to Japan. (How bad is the paleontology, you ask? Bad enough that Yamane identifies the Jurassic Period as occurring 2 million years ago, about 130 million years more recent than its actual date! And remarkably enough, that’s one fuck-up we can’t pin on Al C. Ward, the man Levine hired to write the English-language dialogue.) At the end of the conference, Dr. Yamane reveals his belief that the monster is in some sense the product of American H-bomb experiments, which would certainly explain why everything Godzilla touches becomes radioactive. (Which sense depends on which version you watch. Godzilla: King of the Monsters makes him an atomic mutant like the ants in Them!, whereas Gojira’s Yamane suggests that he is a creature of an unknown but already extant species, driven away from his natural habitat by nuke-related ecological disruption.) The principal result of this conference is that the authorities decide the thing to do is to track down Godzilla with sonar and depth-charge his ass, beginning a proud monster movie tradition.

The flipside of that proud tradition— the miserable failure of depth charges to do any harm to the monster— also begins here. While Japan celebrates what all assume to be the end of the menace, Godzilla gives all six million people of Tokyo the rudest possible awakening by surfacing out in their harbor. He later lumbers ashore and makes his first attack on Japanese territory, leveling Tokyo’s shipping district before returning to the sea for unknown reasons. The next day, the authorities (who are rightly certain that the monster will be coming back) order Tokyo to be encircled by high-tension electrical towers— in essence, the greatest electrified fence of all time. Against all odds, the project is completed in time to intercept the creature when he takes the stage for his encore performance. A fat lot of good it does Tokyo, though. 300,000 volts of electricity (only 50,000 in the Japanese version) turn out to bother Godzilla just enough to make him want to melt a hole in the electric cordon with his thermonuclear breath. Then begins what is almost certainly the single best monster rampage in cinema history, as Godzilla does to Tokyo what Little Boy and Fat Man did to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, effortlessly brushing aside the full power of the Japanese military in the process.

There’s only one thing that might be able to stop Godzilla, but only two people on Earth even know that it exists. One of those people is its creator, Dr. Serizawa. The other is Emiko Yamane. Earlier in the film, Emiko went to see her husband-to-be with the intention of telling him about her developing relationship with Ogata (Akira Takarada, later of The Last War and Latitude Zero), a sailor with a deep-sea salvage company (Levine’s version makes him a marine) whom she now wants to marry instead of the scientist. She never got a chance to deliver her message, though, because Serizawa immediately took her down to his lab to show her his new discovery. What Serizawa had stumbled upon was a chemical process capable of sequestering all the dissolved oxygen in a body of water, rendering that water completely unlivable. Any organism in the water when the chemical (which Serizawa calls the Oxygen Destroyer) does its work will die in a matter of seconds. Serizawa knew instantly that this discovery would be important, but he swore Emiko to the strictest secrecy because, in its present form, the Oxygen Destroyer was useful as a weapon only. Serizawa has been a strict pacifist ever since he was disfigured in the last war, and he hoped to keep a lid on his discovery until he could find a more constructive application for it. After the destruction of Tokyo, Emiko returns to Serizawa in company with Ogata, seeking to persuade him to allow the Oxygen Destroyer to be used against Godzilla. After much arguing and soul-searching, Serizawa consents.

The next day, Serizawa, Ogata, Emiko, and her father (along with Martin and his interpreter, Otomo, in the American version) set off on a sonar-equipped ship to find Godzilla. The beast is swiftly located, and Serizawa and Ogata descend to the sea-floor with the Oxygen Destroyer. What follows may be the most moving scene in any giant monster movie ever; at the very least, it’s in the same class as the death of the titular monster in the original King Kong. The scene operates on two levels. First, there is the fact that Honda portrays the now-doomed Godzilla in a startlingly sympathetic light. When the two divers find him, the monster is resting peacefully on the seafloor— he has no idea what’s coming, and it is all but impossible not to feel strangely sorry for him as the men sneak up on him with their bottle full of death. Secondly, the tragic elements of Serizawa’s character— his tortured idealism, the inner conflict that only people who are brought up in a culture that takes honor and duty very seriously are capable of— come into full bloom here, as he cuts his own lifeline, forcing the crew of the ship to let him die with Godzilla, and thereby making sure that the secret of the Oxygen Destroyer dies as well.

The most important question a person must try to answer when writing about this movie is exactly what it is about Godzilla that has allowed it to become so much more than just another flick about a huge, radioactive monster. I’ve already mentioned the idea that the Japanese have a unique perspective on nuclear power and nuclear weapons, but to say that really only changes the terms of the question without answering it. Because the fact is that I’m not Japanese, and I saw Japanese version of this film only relatively recently, but Godzilla: King of the Monsters still affects me in a way that The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and, for that matter, any of Godzilla’s sequels do not. Part of it, I think, has to do with the way the movie was shot. The grainy, high-contrast black and white of the picture gives the film a moodiness that is almost impossible to achieve in full color. It also works wonders for the special effects by hiding the shortcomings of the monster suit and the miniature sets (though it can’t disguise the crappiness of the hand-puppet Godzilla that Tsubaraya used for a lamentably large number of close-up shots). It is also important to take the score into account. Usually, I barely notice the background music in the movies I watch. With this film, though, any analysis that ignores the effect of Akira Ifukube’s score is missing much of the action. Ifukube is a man who knows what music is capable of, and who knows how best to use it to achieve a desired effect. And because he is both Japanese and old enough to have lived in a Japan that had not yet begun to recast itself so much in the image of the West, he brings to his work a sensibility that differs noticeably from that of Western composers. The total effect is that you really hear his music, and are fully conscious of how perfectly it fits the images to which it is set. Ifukube, by the way, also created Godzilla’s instantly recognizable roar— and I believe the mere fact that Godzilla has an instantly recognizable roar says all that I need to on that subject. Meanwhile, if we’re talking strictly about the American version, it was a minor stroke of genius to have Steve Martin constantly accompanied by an interpreter. Doing so enabled Levine to keep the dubbing (which, I regret to say, is outstandingly awful) to a bare minimum, while providing a subtle psychological crutch for audiences unfamiliar with Japanese culture. Such viewers could be trusted not to notice that the original dialogue almost invariably says something different from the translations Otomo feeds his boss, and having the interpreter around trains a sort of subconscious spotlight on the foreignness of the setting. The latter counteracts the impulse that some might feel to evaluate the characters’ behavior according to Western cultural norms, and to dismiss it on that basis as unrealistic.

But there has to be more at work here than crafty music and cinematography, and I believe that much of it can be found in the nature of the monster himself. Godzilla (at least in this film) is larger than life in a way that the Rhedosaurus is not. There’s his sheer size, for one thing— originally 50 meters (a hair short of 165 feet) in height, and 100 meters from snout to tail, hyperbolically magnified in Ward’s telling to 400 and presumably 800 feet, respectively— which increases the scale on which the movie as a whole operates even before taking into account Godzilla’s possession of abilities that no natural organism should have. The Rhedosaurus kills a couple of people, wrecks a few cars, damages some buildings, and destroys a roller coaster. Godzilla levels all of Tokyo, killing untold thousands in the process. The military is unable to stop the Rhedosaurus solely because it is prevented by a combination of logistical accidents from bringing its full power to bear. Godzilla takes everything the army, navy, and air force can throw at him, and still flattens Japan’s largest city. Basically, Godzilla is the atom bomb in a way that the Rhedosaurus, The Amazing Colossal Man, and Tarantula are not. Godzilla is a force of limitless destructive power, created by a humanity that had no real idea what it was doing, and which can be stopped only if, God help us, we render it obsolete by creating something even worse! Another important point to consider in trying to account for this movie’s curious impact is the fact that, alone among the monster movies that I know of, it dwells at considerable length on the aftermath of the monster’s attack. Think about this. In most movies of this type, the monster is destroyed before it is able to cause any meaningful damage, and even in those rare instances (Gorgo, for example) where the monster cannot be stopped in time, the end of the film coincides almost exactly with the end of the immediate menace posed by it. In Godzilla, on the other hand, the creature’s climactic rampage through Tokyo ends with nearly a third of the running time remaining. Honda has time to show us the ravaged remains of the city, the shell-shocked, homeless, wounded survivors (“human wreckage,” to use a phrase from one of Raymond Burr’s voiceovers)— time, in other words, to show us how Godzilla has affected people’s lives. Look for anything comparable in The Beginning of the End or Earth vs. the Spider, and you will look in vain.

Turning now to the matter of head-to-head comparison between Gojira and Godzilla: King of the Monsters, I’m going to be my usual heretical self by admitting a very slight preference for Joseph Levine’s rendition. Partly that’s just because Godzilla was one of my favorite movies from a very young age, and the US version is the one I grew up with. But I also have substantive gripes with the original edit that, in my estimation, are enough to counterbalance the short shrift given by Levine to the Serizawa-Emiko-Ogata triangle, the craptacular dubbing in those scenes that couldn’t be stretched to accommodate Martin and Otomo, and all those silly shots of Raymond Burr talking to the backs of people’s heads. For one thing, Levine was absolutely right about Gojira’s pacing. The first half of the movie is much too slow, and devotes far too much time to government officials of various ranks holding meetings. By the time we get to the original, longer version of Yamane’s presentation to press and parliament, we’ve become achingly familiar with that conference hall set and others like it. But a more important problem is the original characterization of Dr. Yamane. By eliminating the majority of his scenes, Godzilla: King of the Monsters reduces him essentially to a unidimensional wise man, but this is one instance in which that’s not such a bad thing. The purely Japanese Yamane, toeing what was already a familiar line by 1954, asserts early on that Godzilla is far too important to be destroyed in the cavalier manner contemplated by the authorities. Not only is he possibly the world’s last living dinosaur, but he’s also somehow managed to survive— perhaps even to thrive on— exposure to an amount of radiation that ought to be instantly lethal to anything. If Godzilla could be methodically studied, who knows what biological, paleontological, or medical secrets he would yield? And that’s a defensible stance— the first time Yamane makes it. But when Godzilla’s annihilation of Tokyo finds Yamane sulking in his blacked-out study, blubbering, “Why can’t we use him for science?” there’s no longer any credible justification for such sentiments. You can’t “use him for science” because he’s 50 meters high, and his idea of fun makes the 20th Air Force look like a couple of teenage hooligans playing mailbox baseball, fool!!!! Nevertheless, there is much that got cut from the familiar American version that makes Gojira essential viewing now that it has become widely available in the English-speaking world. The destruction of Tokyo is even more horrific, thanks to a few personal-scale bits that were either minimized by Levine or excised altogether. (That war widow… Holy fuck…) The debate between Ogata and Serizawa over the morality of using the Oxygen Destroyer is made even more wrenching by the extra time devoted to it, emphasizing even more starkly this movie’s status as one of the very few that ever earned a moment as mawkish as that children’s choir singing “Oh Peace, Oh Light, Return” on TV. Serizawa’s principled suicide hits even harder, because the original edit doesn’t treat it as a surprise; Emiko grasps what he proposes to do just a moment after he finally agrees to permit the use of his secret superweapon. So although I prefer Godzilla: King of the Monsters, it is in no sense a substitute for Gojira. You can see both versions easily enough now, so by all means do so.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact