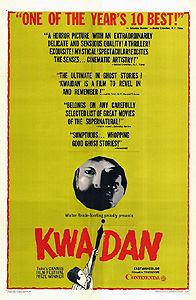

Kwaidan / Ghost Stories / Weird Tales / Kaidan (1964/1965) ***

Kwaidan / Ghost Stories / Weird Tales / Kaidan (1964/1965) ***

If anybody ever merited the appellation, “man of the world,” it was Patrick Lafcadio Hearn. Born on the Aegean isle of Lefkada to a Greek mother and an Irish father, he spent most of his childhood in Dublin before emigrating to the United States at the age of nineteen. As a newspaper writer in Cincinnati, Hearn became known as both an accomplished muckraker and a tireless friend of the downtrodden and marginalized. Hearn’s aggressive free-thinking and love for the disenfranchised wasn’t just a professional matter, either, for his first wife, Alethea Foley, was a black woman— more than simply unconventional, their union was actually illegal in Ohio at the time! But it was in New Orleans, to which he relocated (apparently without Foley) in 1877, that Hearn discovered his greatest talent. Writing first for a succession of newspapers and later for Harper’s Weekly and Scribner’s Magazine, he developed into a folklorist and ethnographer of exceptional ability. He wrote on Voodoo, Creole dialect and cuisine, and all manner of topics that might be placed under the heading of New Orleans folkways, and then repeated the performance in the West Indies a few years later. Finally, in 1890 (and now we begin closing in on the actual point of this ramble), Hearn made a fateful journey to Japan as a newspaper correspondent. The official assignment lasted only briefly, but Hearn’s sojourn in the Land of the Rising Sun would consume the remaining fourteen years of his life. He felt more at peace in Japan than he ever had anywhere else; within his first fifteen months in the country, he married samurai’s daughter Setsu Koizumi, and took the extraordinary (and by no means easy) step of becoming a Japanese citizen. And most importantly, Hearn once again took up his pen to open up a window on the culture of his adopted home. He wrote at least fourteen books during his last decade, ranging from simple travelogues to discussions of Japanese poetry and religion. But what Hearn is best remembered for today is his invaluable work in collecting Japanese folktales, stories of the supernatural especially. Though he wrote primarily for a Western audience, Hearn’s books represent the first written appearance in any language for many of the tales he recorded, and today he is respected at least as much in Japan as he is in the English-speaking world. He is memorialized with monuments and museums in the small towns where he lived (preferring the “purer” life of the Japanese boonies to that of the rapidly industrializing cities of the Meiji era), and his various anniversaries are frequently marked by cultural festivals and academic retrospectives. The way I see it, though, the surest sign that the Japanese have embraced Hearn just as firmly as he embraced them is the existence of the 1964 anthology movie Kwaidan.* Museums and scholarly conferences are all well and good, but when Toho makes a high-profile film based on your writings, that’s when you know you’ve really arrived.

Interestingly, only two of the four stories in the movie are taken from Hearn’s Kwaidan. “In a Cup of Tea,” the last tale, was published in Shadowings, while the opener, “Black Hair,” appeared in Kotto: Being Japanese Curios, with Sundry Cobwebs under the title “The Reconciliation.” The latter is in some respects the most interesting of the four, for it strikingly prefigures a number of themes and images that would come to full fruition in the generation of Asian horror movies made in the wake of Ring— it isn’t for nothing that the story has been retitled “Black Hair.” It focuses on an unnamed samurai (Rentaro Mikuni, of The Possessed) whom we meet as a young man, after he has been driven to destitution by the financial ruination of his master. The samurai knows no trade other than fighting (and at his rank, any other trade would be unseemly anyway), and the efforts of his wife (Michiyo Aratama) to support the household with her weaving have proven a spectacular failure. His reputation as a swordsman is still strong, however, and he has been offered a term of service with another daimyo in a different province. The reason why is more than a little vague, but the samurai evidently believes that accepting the engagement will require him to leave his wife, and he is more than ready to do that if it means that he can get ahead. Accordingly, he divorces her, and takes in her place the daughter (Misako Watanabe) of his new lord. The samurai comes to regret his decision, however. His new wife is vain, status-obsessed, and unloving, and the samurai’s homelife is one of unremitting dissatisfaction. After some five years with the daimyo’s daughter, he decides he can’t take it anymore and divorces her, too. Then, as soon as his term of service to his ex-father-in-law has elapsed, he sets off for his old home, in the hope of making amends with his first wife. To the samurai’s astonishment, she is still living in their old house (most of which has fallen into ruin), scraping by on her weaving just like before. She’s also as lovely as she ever was, scarcely seeming to have aged despite all the years that have gone by. The samurai launches immediately into the most abject apology he can devise (and nobody can apologize more abjectly than the Japanese), to which his former wife responds with complete forgiveness. The reunited couple spend the night together in their original bridal chamber, reminiscing about old times and presumably putting the dilapidated room to its previous use once more. We already know this is a ghost story, though, so we will be unable to share in the samurai’s surprise when he awakens the next morning with his arms around a withered corpse. What is maybe just a little surprising is that even then, the samurai’s day has not yet begun to suck…

The second story (in the original version, anyway— more on this later) is “The Snow Woman.” It concerns a pair of woodsmen from the Musashi province, and unlike any of the last bunch of characters, they actually get names. The old man is Mosaku; his teenage apprentice is Minokichi (Tatsuya Kandai, from Illusion of Blood— one of a great many movie versions of the perennially popular Ghost Story of Yotsuya— and the live-action Hong Kong remake of Wicked City). The two men are on their way home with a load of firewood when a ferocious snowstorm blows up, trapping them in the forest and on the wrong side of the river. The only shelter at hand is the ferryman’s hut, which isn’t much in the face of such a blizzard. In the middle of the night, Minokichi awakens to see that he and Mosaku have a guest, an exceedingly pale woman dressed all in white, and that she is crouching over the old man, blowing her frigid breath into his face. This can only be the Snow Woman, the spirit who personifies freezing to death in Japanese legend. Minokichi figures he’s doomed, but a change comes over the Snow Woman when she turns her attention to him. Pleased by the youth’s handsome appearance, and pitying him for all the years that he will lose if she does her usual job on him, she offers to let him live, on the condition that he tell absolutely no one— ever— about their encounter tonight. If he does blab the story, she’ll know it, and she will seek him out and kill him like she’s supposed to be doing right now. Minokichi agrees to keep the secret, and lives to return home to his mother (Yuko Mochizuki).

The next spring, Minokichi meets a girl on his way home from work. Her name is Yuki (Keiko Kishi), and if you speak Japanese, that’s a huge and obtrusive piece of foreshadowing— Yuki, though common enough as a feminine name, also happens to mean “snow.” Yuki says that she has recently lost both her parents, and that she is now on her way to Edo, where some relatives of hers might be able to help her find work as a domestic servant. That’s a long journey for a girl to be making alone, and it worries Minokichi even more to imagine the danger she places herself in by setting off so close to sunset. Consequently, he invites Yuki to come stay the night in the village with him and his mother, and the two of them hit it off to such an extent that Yuki never does make it to Edo. Instead, she marries Minokichi, bears him three children, and endears herself to all of the neighbors with her charm, devotion, and generosity. Then one night, many years after their initial meeting, Minokichi gets it into his head to tell his beloved wife a little story about his youth…

Next up is “Hoichi the Earless.” This is Kwaidan’s most ambitious segment, and quite a bit of background needs to be laid before the story proper can get underway. Thus we are treated to a lengthy and dreamlike enactment of the final sea battle between the Genji and Heike clans, in the Shimonoseki Straits. As with most naval battles in the days before long-range gunnery, it was an appallingly vicious affair, ending with the complete annihilation of the Heike fleet and the mass suicide by drowning of the Heike emperor’s household and retainers. Ever since then (the narrator’s statement dating the event to 700 years ago interestingly sets the voiceover itself in the late 19th century), that stretch of sea has been considered haunted; the most obvious manifestation can be seen in the human faces that adorn the shells of crabs caught in the waters of the straits, but the supernatural weirdness has been varied enough and serious enough that a Buddhist temple was built on the shore in Akamagaseki, so that priests might always be on hand to placate the restless dead with their prayers.

Hoichi (Princess from the Moon’s Katsuo Nakamura), a blind teenager who plays a mean biwa, is one of the handymen at that temple. The viewer will quickly observe that there is nothing visibly wrong with his ears. It happens one day that Hoichi is left alone at the temple, for the chief priest (Takashi Shimura, from Godzilla: King of the Monsters and Gigantis the Fire Monster) and his entourage are called away to perform a funeral service for some men who died in a shipwreck out in the straits. While the boy sits on the temple porch strumming his biwa, a samurai (Tetsuro Tamba, of Gozu and Black Lizard) accosts him, saying that his master, “a person of exceedingly high rank,” wishes Hoichi to come to his house and perform the songs and poems relating to the Genji-Heike war. Evidently the lad’s reputation as a musician rests especially on his facility with that material. Hoichi makes a lot of noise about being unworthy of such an honor, but the samurai won’t hear of it, and within the hour, Hoichi is picking and chanting away in the audience chamber of what can only be called a palace. I’d call the rank of this particular lord not just exceedingly high, but suspiciously so, especially in light of the markedly antiquated armor worn by his samurai envoy.

As you’ve probably gathered, Hoichi has spent the night entertaining the ghost-court of the long-dead Heike emperor, and each sunset for many days thereafter, the spectral samurai comes to summon him for a repeat performance. Hoichi grows weaker each time, until his friends and coworkers at the temple begin to fear for him. Even the priest takes notice eventually, but Hoichi fends off everyone’s concerns with a succession of vague cover stories, the ghosts having sworn him to secrecy regarding his nightly visits to their court. One evening, though, a fellow caretaker named Yasuku (Kunie Tanaka, from Evil of Dracula and Murders in the Dollhouse) sees Hoichi set off for that night’s performance. Yasuku and another man go in pursuit, and ultimately find Hoichi strumming his biwa in the midst of a cemetery filled with Heike cenotaphs while swarms of will-o-the-wisps circle about him. They drag Hoichi back to the temple, where the priest explains to him what has been going on. This is a serious business Hoichi has entered into, for the spirits of the Heike obviously mean to claim the lad for their own. Luckily for Hoichi, however, the priest knows just what to do in order to break the spirits’ hold: he and his assistants must paint every inch of Hoichi’s body with the text of sacred sutras, so that he will be both invisible and invulnerable the next time the ghostly envoy comes to collect him. Those of you who remember the title of this segment will already have surmised what goes wrong with the priest’s plan— let’s just say he missed a spot…

Finally, we have “In a Cup of Tea,” which differs from its predecessors in having its own little framing story. An author (Ghost Story of Youth’s Osamu Takizawa) rambles to no one in particular about the frequency with which somebody in his line of work comes upon fragments of unfinished fiction preserved in compilations of Japanese literature, and wonders aloud about what could have made their creators break off writing. Then he takes up one of his books, and begins reading exactly such a story. The tale concerns Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura), a middle-aged samurai employed as the chief of security for some daimyo or other. One afternoon, while Kannai is eating lunch in his master’s garden, he sees an unexpected reflection in his cup of tea. The face Kannai sees is not his own, but that of a much younger man, and when Kannai looks around the garden, he can see nobody who could possibly have cast the reflection. The youthful face is still there when Kannai looks back at his cup, and it’s still there when he dumps out the tea and pours himself another serving. Not knowing what else to do (and probably convinced that he’s merely imagining the whole thing), Kannai drinks this second cup, and then goes about his business.

That night, the house Kannai is charged with guarding receives an unexpected visitor. That’s right— it’s the guy from the teacup. He introduces himself as Shikubu Heinai (Noboru Nakaya, from Lady Snowblood), and reproaches Kannai for having “wounded” him that afternoon. Kannai blusters at the intruder, demanding to know what he’s doing at the house and how he got in without rousing any of the other guards. The verbal stalemate continues for a few moments, but Kannai soon loses patience and draws his katana. Heinai vanishes into thin air each time Kannai gets in what should have been a good slash at him, finally disappearing for good into the substance of one of the interior walls. The daimyo’s other men do not find Kannai’s report on the incident persuasive. It probably wouldn’t have helped even if they had, though, because Heinai has retainers of his own, and three of them will be dropping in on Kannai the following evening. The story breaks off right in the middle of the ensuing clash, returning us to the framing story for a denouement that is arguably even less satisfying than that…

When American audiences got their first look at Kwaidan in 1965, they saw it shorn of the “Snow Woman” segment. This makes sense on one level, in that the original Japanese version of Kwaidan runs a butt-numbing 164 minutes, which is probably about 40 minutes too many. Kwaidan’s pace is funereal, its tone reverent in the extreme, and I for one frequently found myself wishing for the movie to get on with it already. Something, somewhere, really did need to go. Why the US distributors chose to excise by far the best of the four segments in its entirety remains a mystery for the ages, however. If I had to pick one of the four stories to forego, I’d ditch “In a Cup of Tea,” which despite an intriguingly outlandish premise (just what would happen to a person who somehow managed to drink a ghost?) and an admirable performance by Kanemon Nakamura as the frustrated and outmatched samurai, is rendered eminently dispensable by its failure to reach a viable conclusion not once but twice. “Black Hair” is also problematic, for although it is easily the most overtly horrific of the four tales, it suffers from some startlingly amateurish directorial missteps. Considering what a masterful grasp of visual storytelling director Masaki Kobayashi displays in the other three segments, his lazy over-reliance on voiceover narration— to say nothing of the maddeningly elliptical approach to plot and character development that makes that over-reliance actually necessary— is simply inexplicable. Nevertheless, the image of the ghost-wife’s long, black tresses writhing with a life of their own about her desiccated body during the climax goes a long way toward compensating for those faults. “Hoichi the Earless” is just a beautiful piece of filmmaking, from the opening battle scene (which resembles nothing so much as a painted silk tapestry in the traditional Oriental style come to life) to the bizarre spectacle of the samurai ghost struggling to capture Hoichi’s ears in order to prove to his emperor that he did at least try to carry out the mission, and its comic relief surprises by earning a legitimate chuckle or two. (“Hoichi the Earless” is the only segment during which Kobayashi relaxes sufficiently to have any comic relief.) “The Snow Woman” is the real triumph, however, and it owes a great deal of its success to the dual performance of Keiko Kishi. She’s maybe a little old for the part as the apparently human Yuki, but she’s just about perfect in her true guise as the Snow Woman. Most notably, the strange stiffness with which she moves her body and even changes facial expressions not only adds immeasurably to the preternatural appearance lent her by the makeup and lighting, but also plays up specifically the idea that she is supposed to represent the living embodiment of lethal winter cold. First-run US audiences seriously got shafted in being denied a look at her.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact