Gigantis the Fire Monster / Godzilla Raids Again / The Return of Godzilla / Gojira no Gyakushu (1955/1959) *** [Japanese version] **½ [US version]

Gigantis the Fire Monster / Godzilla Raids Again / The Return of Godzilla / Gojira no Gyakushu (1955/1959) *** [Japanese version] **½ [US version]

Given how much Godzilla: King of the Monsters owed to the example of King Kong, I suppose it’s fitting that Toho reacted to the success of their genre-defining monster movie in exactly the same way as RKO two decades earlier. As soon as they understood what a hit they had on their hands, they hurried into production a slapdash sequel that completely failed to recapture the first film’s special magic. Indeed, Toho made Gojira no Gyakushu (“Godzilla’s Counterattack”) in even more of a headlong rush than the one that produced The Son of Kong. Although the intervening change of calendar years obscures this, a scant five months elapsed between the domestic release of Godzilla and that of its first sequel! But while I don’t think anyone can credibly argue that the film variously known in English as Gigantis the Fire Monster or Godzilla Raids Again is in any sense equal to its predecessor, I will contend that Toho also played the Emergency Sequel game a lot more effectively than we had any right to expect. What’s more, that’s true even though— and perhaps precisely because— they entrusted most of the task not to the artists of the original creative team, but to a bunch of reliable studio jobbers. Screenwriter Takeo Murata returned (this time with an assist from newcomer Shigeaki Hidaka), as did special effects sensei Eiji Tsuburaya, but Ishiro Honda and Akira Ifukube were already attached to other projects. Their places were taken by Motoyoshi Oda, a director whose primary talent was a proven ability to crank out a movie quickly, cheaply, and efficiently, and Masaru Sato, who would later become a composer of significant standing, but in those days was just a 20-something kid with a two-year track record. These were not the people you wanted if the object was to perform a mythic exorcism of Japan’s lingering national traumas, but if all they needed to make was a monster movie, then they could do a pretty bang-up job.

Shoichi Tsukioka (Hiroshi Koizumi, from Mothra and Atragon) and Koji Kobayashi (Minoru Chiaki) were military pilots during the war, but now they fly for the Osaka branch of the Kaiyo Fishing Company. Together they patrol the skies over the nearby fisheries looking for big schools of fish swimming close to the surface, radioing the dispatchers at headquarters with their findings in order to vector the Kaiyo cannery ships toward their targets. One of those dispatchers, by the way, is Hidemi Yamaji (Setsuko Wakayama), daughter of cannery boss Koehi Yamaji (Yukio Kasama), to whom Tsukioka is engaged. The other is Yasuko Inouye (Mayuri Mokusho), who delights in making herself an “entertaining” nuisance to her friend on the subject of her office romance. Kobayashi has a girl as well, but he’s too shy ever to talk about her, and only Hidemi so much as suspects her existence. By far the biggest difference between the Japanese and American cuts of the film concerns the length and depth of the shadows cast by those relationships. The original edit gets pretty badly bogged down with them, whereas ours prunes the soap opera so severely that the women barely even register as characters. Having finally had the chance to compare the two, I’m frankly not sure which approach I prefer.

Regardless, one day out on the job, the two pilots find something very different from the cod and bonito whose movements they normally track. Kobayashi is forced by engine trouble to ditch his plane in a treacherous patch of sea full of craggy islets and barely-submerged coral reefs. He brings his floatplane to a safe, soft landing against the odds, but he is now stranded on one of those nasty little rockpiles, and Tsukioka is more or less his only hope of getting home. And just his luck, Kobayashi has managed to choose as the site for his emergency landing the islet where two gigantic monsters are busily slugging it out. How two different pilots could have failed to notice such a thing from the air I have no idea (my admittedly limited experience suggests that 50-meter reptiles aren’t exactly unobtrusive), but after stumbling upon the battling titans, they waste no time in climbing into Tsukioka’s plane and flying home.

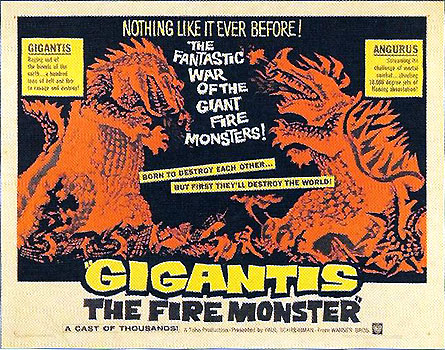

If this were an American movie, nobody would believe Tsukioka and Kobayashi’s story, but in Japan, the Proper Authorities take the possibility of attack by giant monsters very seriously— especially when the eyewitnesses are pretty sure one of the creatures in question was Godzilla. True, Dr. Serizawa’s Oxygen Destroyer annihilated Godzilla so thoroughly that there wasn’t even a carcass to recover, but you’ll recall that Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura, who returns for a brief cameo in Gigantis the Fire Monster) warned that other such creatures could very well exist, just waiting to be goaded into action by the superpowers’ nuclear weapons experiments. No sooner has the pilots’ story gotten out than they are confronted by a gaggle of scientists bearing copies of Edwin Harris Colbert’s The Dinosaur Book to use as a sort of improvised mugshot gallery in the hope of identifying Godzilla’s opponent. (In the American dub, Tsukioka hilariously describes looking at “photographs of every known prehistoric monster.” Photographs, mind you.) Here again, the alternate edits offer us a choice, only this time the options are two distinct visions of riotously bad paleontology. In the original, Dr. Tadakoro (Masao Shimizu, from Sanjuro and The Snow Woman), the paleontologist debriefing the pilots, explicitly identifies the spiky-backed, turtle-like creature which Tsukioka and Kobayashi saw on the islet as an Ankylosaurus (“also known as Anguirus”), which he then goes on to describe as a fast, agile, aggressive carnivore— and any child could have told you that was wrong on all counts, even in the mid-1950’s. The US version, on the other hand, has Tadakoro and Yamane ramble incomprehensibly about “the Gigantis monster, of the Anguirus family” amid utter fucking nonsense about an age of fire millions of years ago and a prophecy about fire monsters returning to life thanks to radioactivity. The other thing you’ll notice about the American dub is that it never so much as mentions the name “Godzilla.” Producer Paul Schreibman claimed to have wanted to avoid “confusing” the target audience with the possibility that this movie was a revival of Godzilla: King of the Monsters, but I suspect the real issue was one of territorial pissing between him and Joseph Levine. After all, what the hell could be more confusing than to deny that this is a Godzilla movie while bringing back Dr. Yamane to show clips from Godzilla’s second attack on Tokyo, to recount the tale of the Oxygen Destroyer, and to lament that the loss of the formula for Serizawa’s superweapon leaves the world with no realistic prospect of destroying the re-emergent monster?

With no Oxygen Destroyer to fall back on, the ministry of defense is forced to content itself with trying to keep the monsters from coming to Japan in the first place. It is Yamane’s belief that Godzilla is attracted to light, and thus preparations are made to black out any coastal city that seems likely to be on the creature’s itinerary. And as an added insurance policy, squadrons of fighter-bombers are outfitted with special long-burning flares which they are to drop on Godzilla’s seaward flank should he in fact surface near the shore. These precautions are undertaken not a moment too soon, for it is only a matter of days before Godzilla appears just off Osaka. The blackout is put into effect, the flare-dropping planes are scrambled, and at first, it looks as though this simple but reasonable plan might actually work. But the ministry of defense didn’t figure on a busload of convicts being evacuated from prison on the night that Godzilla appears. The thugs’ ringleader hits upon the idea of exploiting the Godzilla-related confusion to provide cover for an escape attempt, and their plans come even closer to success than the military’s before one of them loses control of the hijacked van in a high-speed chase, and plows it into the side of an oil bunker in the shipping district. The resulting explosion captures the attention, not only of Godzilla, but of Anguirus as well, and both monsters wade ashore to wreak havoc. Before long, Godzilla and Anguirus have found each other and resumed their brawling, and by the time the former monster slays the latter, there isn’t a hell of a lot left of Osaka.

Present-day viewers will no doubt be baffled by the placement of the big monster fight in the middle of the film, especially once they see the comparatively desultory sequence that Oda has in store for the climax. Remember, though, that Godzilla: King of the Monsters played it the same way, and that the lion’s share of that movie’s power stemmed from the sober deliberation with which it dwelled on the aftermath of the monster’s attack. That’s obviously the plan in the sequel, too, but unfortunately the object of the current round of sober deliberation is not the annihilation of a major city, but rather the efforts of Mr. Yamaji to rebuild the Kaiyo Fishing Company around its Hokkaido branch office. It isn’t the same thing at all, and even in the Japanese version, the only gesture that Gigantis the Fire Monster ever makes in the direction of the nation’s psychic scars is an underdeveloped subplot about Tsukioka and Kobayashi reconnecting with the other survivors of their old unit in the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service. This is also where Oda starts trying extra-hard to make us care about Tsukioka and Hidemi’s impending nuptials, and about Kobayashi’s secret girlfriend, without giving us much reason to do so. Eventually, though, it is revealed that Godzilla has come out of hiding to sink one of Yamaji’s ships, and the movie gets down to business again.

Naturally the main responsibility for locating and neutralizing the monster falls on Captain Terasawa (Senjiro Onda, from Throne of Blood and The Invisible Avenger) and the rest of Tsukioka and Kobayashi’s old pals who still do their flying under arms, but the civilian pilots nevertheless determine to do their parts on a volunteer basis. And because that’s how it always works in monster movies, it ends up being Tsukioka who first sights Godzilla, lounging around on another islet far from the Japanese mainland, this one an inhospitable little iceberg of a place halfway to the Aleutians. An airstrike is launched at once, but Tsukioka’s plane is too low on fuel for him to stick around and point out the monster’s location to the jet jockeys. So Kobayashi flies out to relieve him, and is thus in the area when the fighting breaks out. Godzilla isn’t a terribly discriminating creature, though, and doesn’t much care for the distinction between a light commercial floatplane and an F-80 Shooting Star. The monster figures Kobayashi is part of the attack, and in a brief moment when no bombs are bouncing uselessly off his impenetrable hide, shoots the pilot down with a blast of his atomic breath.

But Kobayashi isn’t killed instantly, and as his plane falls from the sky, he makes a desperate attempt to kamikaze Godzilla. And though he misses his target, he gets to be a hero anyway, in that his sacrifice inadvertently suggests a way to defeat the monster. Kobayashi’s plane crashes into the ice-cliff above Godzilla’s head, and brings huge quantities of ice and rubble raining down on him. Because the monster’s lair is at the blind end of a deep, narrow box canyon, it ought to be possible to bury him completely, if only enough ordnance were dropped on the surrounding cliffs. The fighters are scrambled once again, and this time, their mission is a resounding success.

I’ve been snarkily critical of Gigantis the Fire Monster so far, but the fact is, it’s the Godzilla sequel I watch most often, even though there are several others which I would not only identify as better, but would also rank higher on my list of personal favorites. Fail though it might to realize its ambitions, this film has a seriousness of purpose that’s both in line with its predecessor and starkly at odds with all but a handful of its numerous successors. The somber black and white cinematography, while unable to match the impact of the original, at least manages to approximate it. The earlier revelation of the monsters enables a considerably snappier pace than even the leaner American cut of the first movie, at least until the sequel stumbles to a halt with the move to Hokkaido. And there are a few easily missed details that show Murata and Hidaka building upon the story so far in a way that few of the later Godzilla installments would bother with. Notice, for one thing, that the evacuation of Osaka turns Godzilla’s return into little more than a matter of property damage, while the military makes only a token effort to defend the empty city. Gigantis the Fire Monster thus presents us with a government that has learned and adapted to a kaiju-haunted world. Similarly, the endgame strategy of burying Godzilla under an avalanche grows more resonant the more you think about it in terms of the first film’s atomic allegory. Godzilla, like the atom bomb, is now here to stay, and the best that can be done with him is to contain him.

But the greatest strength of Gigantis the Fire Monster is that by introducing Anguirus, it contributes something truly new and exciting to the monster movie formula. Literally dozens of “versus” movies later, it’s easy to lose track of this, but Gigantis was the first film of its kind to make combat between equally matched monsters its thematic and conceptual centerpiece, fulfilling at last the promise of King Kong’s theropod sequence. And whereas later kaiju eiga would tend to anthropomorphize such fights, showing the monsters behaving like martial artists, sumo wrestlers, or superheroes, these incarnations of Godzilla and Anguirus are depicted simply as brutal, vicious animals, bent on each other’s destruction and flattening without a thought anything else that gets in the way. There’s nothing else quite like it in the entire canon of Asian rubber-suit monster flicks.

Unsurprisingly, the simplest way to appreciate this movie’s virtues is to watch it in the form its creators intended, but that wasn’t an easy thing to do until fairly recently— and it still may not be a cheap thing to do. If you get stuck with the version that Paul Schreibman released through Warner Brothers in 1959, you can really expect to work to get much out of it. The most vexing aspect of Schreibman’s edit is the almost literally neverending voiceover narration by Keye Luke as Tsukioka. As if he were the presenter of a clumsy radio documentary, he drones on and on, describing in excruciating, absurd detail everything that occurs on the screen. Only during the big showdown between the monsters does he shut up for any length of time. What’s really curious, though, is that this incessant color commentary doesn’t seem to have been intended, as one often sees in Jerry Warren’s Latin American imports, to obviate the need for dialogue dubbing. Scenes of actual conversation between characters are handled normally, if not with any great skill. Rather, it appears that Schreibman believed his target audience to be simply incapable of tolerating silence— a quality with which Gigantis the Fire Monster was originally unusually well endowed for a monster movie.

Schreibman vandalized the audio in several other ways, too. Very little of Masaru Sato’s score remains, its place taken by a variety of bland and overly familiar cues lifted from earlier American B-movies. Normally I wouldn’t mind that so much, since Sato’s desperately hip jazz stylings don’t agree with me at all, but on this particular occasion, he turned in a quite passable Akira Ifukube impersonation (albeit noticeably sparer and more minimalist than the real thing). Certainly Sato’s work was more fitting than this confection of leftovers from Kronos, It!: The Terror from Beyond Space, and so forth. Schreibman tampered with the monsters’ vocalizations as well. Evidently he didn’t care for Godzilla’s famous reverberating roar, because his sound editor systematically went though the entire film, replacing it with Anguirus’s annoying bleat. But hands down the most insulting change to the audio in the American version, to audience and character alike, is the way it handles Kobayashi’s dialogue. In Oda’s hands, Kobayashi was at least coequal to Tsukioka as protagonist, and there’s a sense in which he’s the true hero of the story. But Hiroshi Koizumi was handsome, while Minoru Chiaki was a big, paunchy galoot with a myopic squint and the face of a gargantuan baby. Kobayashi thus looked like the comic relief, and so Schreibman turned him into that by dubbing him with a Barney Rubble dumb-guy voice. It’s still possible to discern the much better movie that Gigantis the Fire Monster originally was through all the distributor sabotage, but like I said, you really do have to work for it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact